It has become arguably the most controversial law in Quebec’s history. Proponents claim it saved the French language in Montreal and ensured Quebec’s cultural future. Detractors call it divisive, a form of legalized bigotry. But on Saturday, the fortieth anniversary of Bill 101, none could deny the lasting impact the legislation has had on the province.

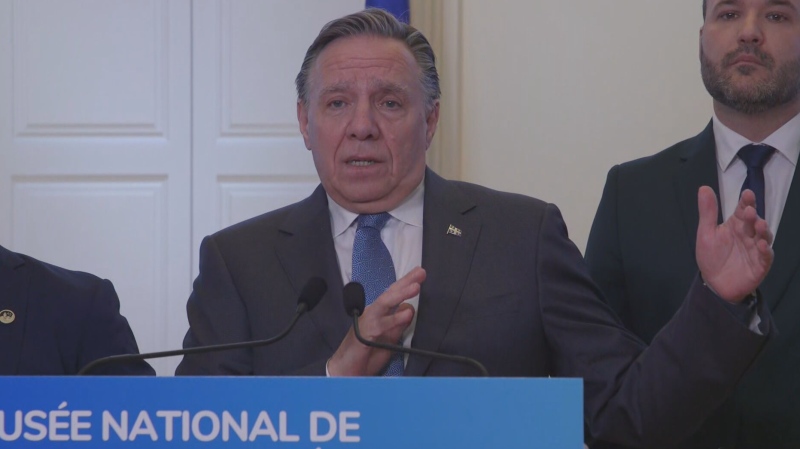

At a gathering to commemorate the anniversary in Montreal, Parti Quebecois leader Jean-Francois Lisee hailed Bill 101 as a groundbreaking law that came during a time when “there were signs of decline of French in Montreal,” including declining enrollment in French schools.

“Change is painful sometimes,” he said. “I think the Anglo community went through a trauma and a change. You couldn’t have thought then that a huge majority of Anglos would now be bilingual, fluent and at ease in this new situation.”

On Aug. 26, 1977, Bill 101 was given royal assent by Quebec’s lieutenant governor, making it officially law. It reconfirmed French’s status as the sole official language of the province and introduced stringent regulations on who would be eligible to receive a public education in a language other than French.

The festivities were fittingly held in Camille-Laurin Park, named after the late Parti Quebecois MNA who is considered the father of Bill 101. Bloc Quebecois leader Martine Ouellet called Laurin a “visionary,” who ensured the survival of French institutions.

Still, supporters have said the bill doesn’t go far enough. Ouellet called for the law to be strengthened, saying “We should go further with Bill 101, especially for working languages and all companies of 25 employees and more should be under Bill 101, too.”

In June, Lisee expressed a desire to see Quebec’s language laws toughened up, saying some companies were not complying with the spirit of Bill 101.

Throughout its history, Bill 101 has drawn fire from Anglophone activists. Among its most vocal opponents is Montreal attorney and English-rights activist Harold Staviss, who said skilled immigrants are avoiding the province due to the language laws.

“Forty years later, unfortunately Montreal and the province have been destroyed,” he said, citing the large exodus of English-speakers in the wakes of the 1980 and 1995 referendums. “Montreal was on the map. Toronto, I remember growing up was a nothing city. Now you go to Toronto and it’s booming. Montreal is not booming.”

Staviss pointed to a recent poll showing most Quebecers would like to be able to choose whether to send their children to English schools as proof the Bill should be repealed but Lisee said Quebec will always have “tension” between individual rights and the need to protect the province’s Francophone identity.

“You will see these polls come and go because there’s this tension between the two,” he said. “But in the end, when you make the decision, you always have strong support for these collective decisions and when you ask the individual if they’d like to have this choice, they will always say ‘yes.’”