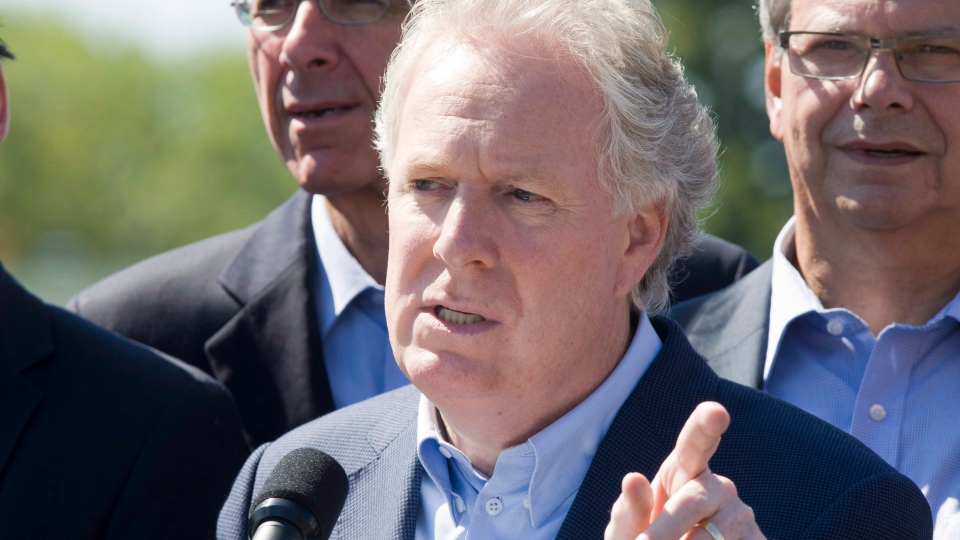

MONTREAL--It's a testament to Jean Charest's reputation as a political survivor that on the day he announced his plans to get out, after three decades in public life, his peers were already abuzz about whether he might someday be pulled back in.

After a lengthy career that spanned nine federal and provincial elections and a stormy nine-year run as Quebec premier, Charest announced Wednesday that he was "going home now."

His experiences as a Brian Mulroney cabinet minister, a referendum campaigner in 1995 and a provincial premier placed him at the forefront of many of the defining political events of a generation.

With a tear in his eye, Charest announced his exit bowed but not broken. After five provincial elections Charest had finally lost the popular vote in one of them -- by a single percentage point Tuesday.

While Charest's Liberals were swept from office, and he lost the riding he has long represented, he was spared the sort of ignominious electoral death predicted so often for him, over so many years.

In a form of poetic symmetry, his defeat on Tuesday was 28 years to the day after he first won office as a young lawyer in Sherbrooke, Que.

He was repeatedly written off in the intervening years. A group of parliamentary reporters in Quebec City, gathered for dinner on the eve of the 2003 election call, chatted about his dismal poll numbers and burst out laughing when one quipped that Charest might turn it around because he was a good campaigner.

A few weeks later, he won a majority government. He won a minority four years after that. Then he won another majority, before losing by four seats this time.

The Liberals finished a surprise second in the Quebec election, defying pundits and pollsters who had predicted a meltdown.

Charest, 56, leaves his party as the official Opposition with a minority government across the aisle.

The party's outgoing leader presided over one last cabinet meeting in Quebec City on Wednesday afternoon. Several ministers were in tears as they emerged.

Standing in front of six Quebec flags in the foyer of the provincial legislature, Charest announced he would step down as party leader as soon the PQ officially formed its government.

"The big Quebec family gathered yesterday, Sept. 4, to choose a new government," Charest said in Quebec City.

"Amid that decision my immediate family also met for a consultation on our future. I announce to you a unanimous decision."

Charest spent the first part of his career as a protege of Mulroney and the wunderkind of the old Progressive Conservatives. He was the youngest cabinet minister in Canadian history at age 28 and was party leader by the time he turned 40.

He gained further national exposure while campaigning for the No side in the 1995 referendum. His fiery, passport-waving speeches were a mainstay of federalist rallies.

But he left federal politics in 1998 to take the helm of the Quebec Liberals, who were leaderless and fretful over the prospect of another referendum.

In much of English Canada, Charest was seen as sacrificing a bright career with the Tories for the sake of keeping the country together -- he earned the tongue-in-cheek moniker of Captain Canada.

Quebec didn't easily warm to the prodigal son returned from Ottawa.

Charest won the popular vote in 1998, while losing to the PQ, and then he strung together three consecutive election wins -- a feat unmatched since the 1950s. But he also suffered through record-low approval ratings through much of his tenure and faced massive popular unrest in recent months.

His political skill may have earned the respect of Quebec voters, but not everyone's love.

After voting in his home riding of Sherbrooke, Que., on Tuesday, a small crowd chanted "Na-Na-Hey-Hey-Goodbye." A few months ago, student protesters repeatedly gathered outside his family home in Montreal. At some protests, he was hung in effigy and people chanted about him being dead.

None of it, though, appeared to faze Charest.

"I loved every day I spent in office, including the most difficult ones," Charest said in his farewell speech Wednesday.

Charest's experience, in Quebec politics, has sometimes been compared to that of a cat with nine lives. So it was perhaps inevitable that his actual departure, when it was finally announced Wednesday, only prompted talk of his next improbable comeback.

Within moments of Charest announcing his decision, some federal Liberals were already inviting him into their tent.

Ontario's Liberal agriculture minister, Ted McMeekin, tweeted that he was "hearing from many that they would support this great and charismatic federalist to lead the Federal Liberals."

The interim federal Liberal leader, Bob Rae, expressed the hope that Charest not lose his desire to be politically involved.

"There's always a home for Mr. Charest in the federal Liberal party," Rae said. "But I take it from his decision today that he's not contemplating continuing in a political life. For some reason, I can understand that."

NDP Leader Tom Mulcair, who once served in Charest's cabinet and had a falling out with the premier, said Wednesday that his old boss is still young and has "a full career" ahead of him.

From a national perspective, Charest's defining achievement will likely be the nine years worth of relative constitutional peace he brought Canadians and Quebecers.

He was among the rare prominent voices for Canada after the federal Grits' electoral woes following the sponsorship scandal.

Charest showcased his unabashed love for Canada in his last speech as premier.

"We are all blessed to have been born in this country, to share its wealth and we're blessed to have each other," he said in English, after making a brief reference to Canada in French.

"I wish that, every day, each and every one of us could feel and understand how much of an opportunity it is for us to live here... There's no other place that I would want to be."

Charest's legacy within Quebec's internal politics is more uncertain.

He tried to move Quebec farther away from state intervention but faced howls of protest from the province's powerful unions.

He promised to cut income taxes, and he did, but later hiked user fees for services including health care and tuition.

He created a long-term program to pay down the debt, the Generations Fund, but the province's already-heavy debt swelled under his watch.

He entered office declaring that health care would be his priority and promised shorter hospital wait times. His opponents suggest Quebec's hospitals are comparably worse off today.

And he now describes the ambitious Plan Nord as key to his legacy but his foes call it a marketing gimmick. It doesn't take a premier to force mining companies to extract diamonds and other minerals, they say.

Charest created new transparency rules, tougher fundraising laws and a corruption inquiry. But this was after two years of controversies, one of which involved a Charest cabinet minister charged with fraud.

His last months in office were dominated by the tuition dispute that triggered huge protests and made international news last spring.

Charest fought an aggressive campaign against his critics.

Despite his ex-cabinet minister Tony Tomassi facing criminal charges, he defied his opponents on the campaign trail to prove his government was corrupt. The issue died down after the campaign's first week.

He also campaigned against his own protesters, calling upon a "silent majority" of Quebec voters to impose law and order. Judging by the final election score, the silent majority fell just a few decibels short of restoring him to office.

But in leaving politics, Charest exposed a softer side that may be unfamiliar to many Quebecers. As he spoke about how he would soon become a grandfather, he broke into tears.

"I'm going home now," Charest said as he wrapped up his speech. "And I thank you for having given me the privilege of being your premier."

History

Charest was born and raised in Sherbrooke and was first elected to Parliament in 1984 as a member of the Conservative Party.

In 1986, at age 28, he was appointed to Brian Mulroney's cabinet as Minister of State for Youth.

In 1993, Charest ran unsuccessfully to become leader of the Conservative Party, losing out to Kim Campbell. However he was one of only two Conservative MPs to return to Ottawa that year, and was named interim party leader until assuming the permanent title in 1995.

Charest was under considerable pressure to switch from federal to provincial politics following his performance in the referendum campaign on sovereignty, and in 1998 agreed to become leader of the Quebec Liberal party.

"You know it , but I will repeat it, I love Quebec," said Charest.

In his first provincial election the Liberals won more votes than the Parti Quebecois but that failed to turn into enough seats to form government.

It was only in 2003 that Charest led the Liberals to power, in what became the first of three consecutive terms as government, the first time this had happened in Quebec in decades.

On Sept. 4, 2012, 28 years to the day after he was first elected, Charest lost his seat to former Bloc Quebecois MP-turned-PQ candidate Serge Cardin

Concession speech

In his concession speech on Tuesday night Charest profusely thanked his family, his team, and voters in his riding, while poking fun at polling firms.

"I want to thank Liberal voters who turned pollsters into liars," said the outgoing premier.

"The resuts show us that the next government will be a minority and a National Assembly that will will have Liberal MNAs in almost every region of Quebec."

Charest congratulated Pauline Marois on being elected the first female premier of Quebec, yet also proudly pointed out that most voters did not choose the Parti Quebecois or sovereignist parties.

"I am also very proud to be Canadian. I want to say to all of you interested in the future of Qubeec the result of this election campaign speaks to the fact that the future of Quebec lies within Canada," said Charest.

He also congratulated Francois Legault on his party's success in winning nearly 20 seats in the National Assembly.

The overall voter turnout was 74.6 percent, a much stronger turnout since the last provincial election, when only 57 percent of Quebecers cast their ballots.

Follow the CTV Montreal Live Blog

--with files from The Canadian Press.