MONTREAL -- As the Jurassic Period ended, sea levels rose, and the supercontinent Pangea was splitting into north and south landmasses.

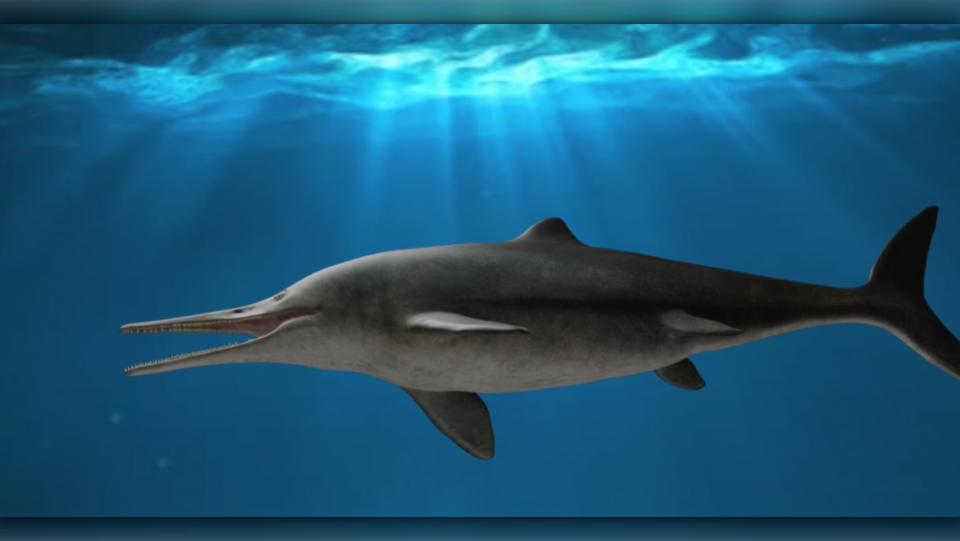

During this early Cretaceous period, a huge swordfish-like ichthyosaur swam the seas above what is now Colombia. Until now, it had no name.

Kyhytysuka, A 130-million-year-old marine fossil, has given researchers a glimpse of the world under the Early Crustaceous sea and is adding new fruit to the evolutionary tree for that time period.

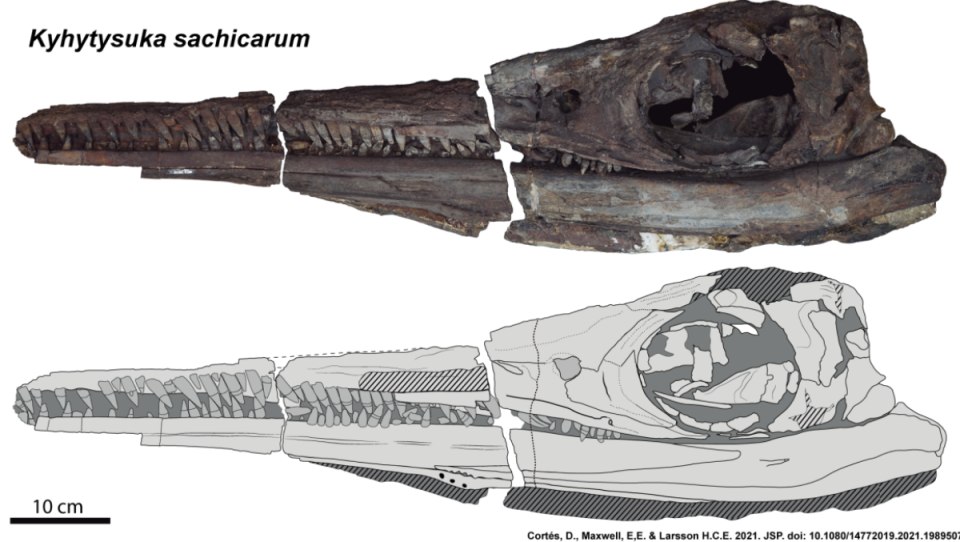

The one-metre-long Kyhytysuka skull spent time in a drawer at the Geological Survey in Bogota after being discovered by local collectors from the Colombian town of Villa de Leyva, on a high-altitude plateau a few hours north of Bogota.

An international team led by McGill University's Redpath Museum director Hans Larsson took a longer look at the skull, which had been not properly categorized.

"It was described a few years ago -- I guess maybe 15 or so years ago -- in a sort of like a cursory paper that just gave it... like a garbage-bin name used for all Cretaceous ichthyosaurs anywhere in the world, because people didn't really know more about it," said Larsson, who led the study.

Larsson has been working in Colombia for the past decade and is particularly interested in the central, high-altitude area where the fossil was discovered.

Larsson has been working in Colombia for the past decade and is particularly interested in the central, high-altitude area where the fossil was discovered.

It and, he suspects, future specimens will help illuminate a particularly fascinating time for paleontologists.

"It comes at a time and a place that is just so exciting in Earth's history," said Larsson.

"In the late Jurassic, there was this global sort of cooling [so] that there were even ice caps on the poles -- and also an extinction event, so lots and lots of animals and plants became extinct.

"The proto Atlantic and Pacific Oceans met for the first time, and they met right in Colombia," he said.

"So you have these sort of clashes of ecosystems coming together over increasing global temperatures and increasing sea levels, and this is the perfect storm for biodiversity."

Dirley Cortés was in high school at the time of the fossil's discovery and started working on putting the it together. Cortés is now a Ph.D. student in Larsson's lab, working out of Panama.

The fossil is part of a clear family line, whose necks were getting longer over time, he said.

“Many classic Jurassic marine ecosystems of deep-water feeding ichthyosaurs, short-necked plesiosaurs, and marine-adapted crocodiles were succeeded by new lineages of long-necked plesiosaurs, sea turtles, large marine lizards called mosasaurs, and now this monster ichthyosaur," said Cortés

Kyhytysuka is one of the last surviving ichthyosaurs with unique teeth, mouth and throat formations that have not been seen before.

“We compared this animal to other Jurassic and Cretaceous ichthyosaurs and were able to define a new type of ichthyosaurs,” said one of Larsson's former graduate students, Erin Maxwell of the State Natural History Museum of Stuttgart.

“This shakes up the evolutionary tree of ichthyosaurs and lets us test new ideas of how they evolved.”

It is the first of many the team will be looking at.

"We have another half-dozen animals coming out of here, and every one gets weirder and weirder," said Larsson.

LESSONS FOR 2021

Larsson said there are two major points of relevance to today's world.

First is the obvious parallels between a warming climate in 2021 and the world 130 million years ago.

"It has these very similar environmental shifts. These happen over a much longer period of time, and the animals and plants, the whole ecosystems, were way different than then than they are right now," but there may again be similar shifts, he said.

"Our end goal in this whole route is to be looking at how ecosystems change throughout this major transition in Earth marine systems."

Reconstructing the Jurassic and early Cretaceous ecological food webs and their complexities helps explain what actually happened as the earth cooled and then warmed.

With many whales and most sharks currently endangered and much of the ocean depopulated, however, Larsson admitted that the oceans look very different than they did when Kyhytysuka swam the seas.

The second benefit is one researchers like Larsson's Montreal team see on the face of children when they head to the Redpath Museum, look up and gape at the massive bones of dinosaurs and other creatures that lived long ago.

"It's such a cool fossil and it really draws a lot of public interest, including with kids," he said.

"While that sounds a bit non-sciency, I can stress that most kids become interested in science through dinosaurs. The value of developing these really far-out species that lived millions of years ago... They're like dragons, except that they really were real."

The new discovery, Larsson said, is just the tip of the iceberg.

"There's so much out there," he said.

The Kyhytysuka bones helped the researchers explain more of the evolutionary tree.

"Everything starting to make a little more sense now," said Larsson. "Now we're able to start getting further and further into the actual biology of these animals."

Those who want to check out a similar ithyosaur can head to the Redpath Museum. A cast of Kyhytysuka will soon be available.