With February marking Heart Month, survivors of heart disease and health practitioners are raising the alarm over an illness that is the leading cause of death for Canadian women.

Susan Rodrigues said she was standing in line at the bank when she felt a sharp pain in her ear and jaw.

“I was sweating profusely, dripping, very hot, dizzy, nauseous,” she said. “I walked out of the bank and sat on a bench. By the time I sat on the bench I thought I was going to be sick. Then, my arm started to get numb.”

Her family took Rodrigues to the hospital, where she was told she’d had a heart attack at only 40-years-old.

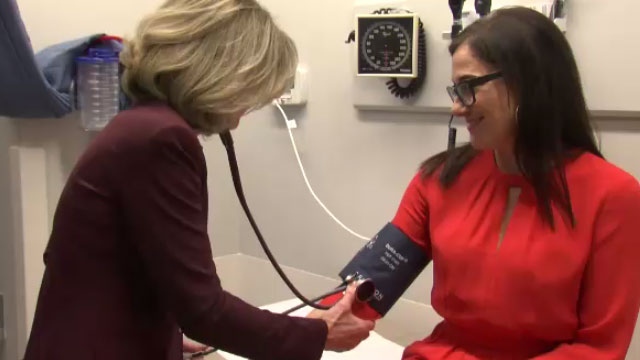

Her case isn’t abnormal, according to Wendy Wray, a nurse who runs a prevention clinic at the McGill University Health Centre.

“They’re generally shocked because they didn’t expect it,” said Wray. “Looking back, sometimes they’ll recognize they had risk factors they hadn’t really put together.”

In Canada, one out of three women will die of heart disease or stroke, a rate that’s higher than breast cancer.

“Women lack awareness of their risk of heart disease,” said Wray. “Women are underdiagnosed, we are also undertreated and we are also under-researched.”

Among the risk factors are a family history of heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, physical inactivity and stress. There are also a wide array of warning sides.

“They’ll have that chest discomfort, but they’ll also feel unwell,” said Wray. “They’ll be short of breath, a little bit sweaty, feeling nauseated, even vomiting and an unusual fatigue.”

Rodrigues said fatigue had set in for her years before her heart attack.

“I really thought it was the cost of running a business, having a family and travelling a lot,” she said. “I really didn’t put it together and neither did my GP.”

Rodrigues learned how to modify her lifestyle at Wray’s clinic – she now works and travels less.

“It’s really a different balance now,” she said. “There’s a grieving process for the loss of that woman.”

She said she hopes other women learn from her example and get their hearts checked without ignoring the symptoms.

“Even if it turns out not to be a heart attack, that’s okay,” said Wray. “Better to go and check.”