The coroner's report into the disappearance of Julie Surprenant concludes that Richard Bouillon likely raped and killed the teenager.

Bouillon lived above the Surprenant home in Terrebonne, Quebec, when Julie disappeared on Nov. 16, 1999.

He had a lengthy criminal history that included rape, sexual assault, molestation and drug trafficking.

As he lay dying of cancer in a hospital in Laval in 2006, Bouillon confessed to nurses that he raped and killed Julie, and wanted to talk to reporters about his actions.

Two correctional service guards also heard the confession.

Bouillon was never given the opportunity to make that phone call, but police officers spoke with hospital officials soon after his death.

Those officials told police that Bouillon had confessed to several crimes, including the murder of Julie Surprenant, but officers did not make any further investigation.

In 2011 the case was re-opened when the Annick Prud'homme, the auxiliary nurse to whom Bouillon confessed, watched a television program and learned that the Julie Surprenant case was unsolved.

For five years, Prud'homme had mistakenly believed that what she had told her superiors had been passed onto police, and that Bouillon had talked to journalists.

Upon learning that was not the case she contacted reporters and told them of the confession, triggering the re-opening of the coroner's inquiry, along with new but unsuccessful searches for Julie's body.

Coroner Catherine Trudel has concluded that, based on the confessions to witnesses, that Bouillon likely raped and killed Julie.

However the coroner leaves two questions open as being beyond the scope of her report, namely whether the public should have access to more information about sexual criminals, and when medical professionals should be obliged to reveal secrets about their clients.

Trudel wrote that Surprenant's father had tried and failed to find out more information about his neighbours, including Bouillon, but was unsuccessful because he did not know the man's birthdate.

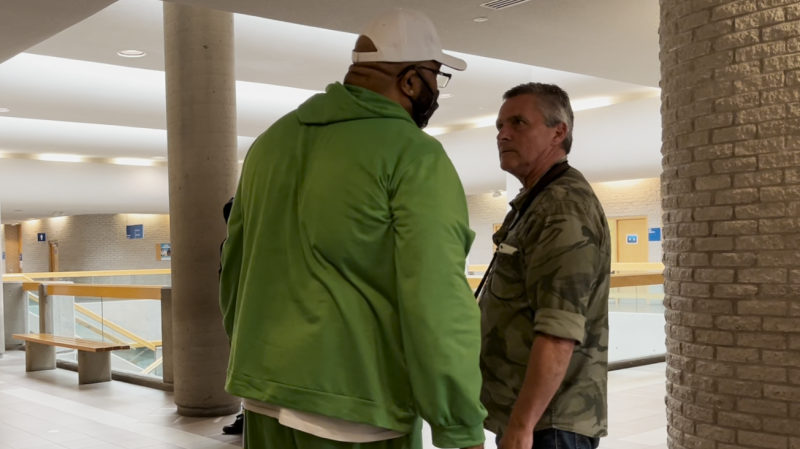

Suprenant’s lawyer, Marc Bellemare, said that’s unacceptable.

“I should be able, easily, to know if there’s a criminal case (against someone), but right now it’s impossible to get it if I don’t have their birth date,” he said.

Trudel also wrote that while nurses are obliged by law to keep medical secrets, they are allowed to reveal that information whenever the client or the law authorizes them to do so.

Michel Surprenant said he was pleased with the conclusion, but this raises the questions about patient-client confidentiality -- and that professional secrets shouldn't be kept if they can help solve crimes.

“I read the report several times and I’m happy about the open mind the coroner gave us, and the chance to go further in this debate,” he said.

“This remains in my life; it remains something active. It remains a debate on which there’s still much to do, because it took 12 years, step by step, to get where we are. The think the debate is moving forward. We’re going to knock on doors everywhere.”

Bellemare said sex offenders’ names should be made more accessible.

“There are 5,000 sex offenders in the federal register right now, and they can move privately and quietly," he said.

"Every single father, every single mother should know, if they want to know, if their neighbour is a sex offender. If you have this possibility, you will be able to prevent any kind of aggression against yourself and against your children, and I think that's the debate that the coroner is opening with this report.”