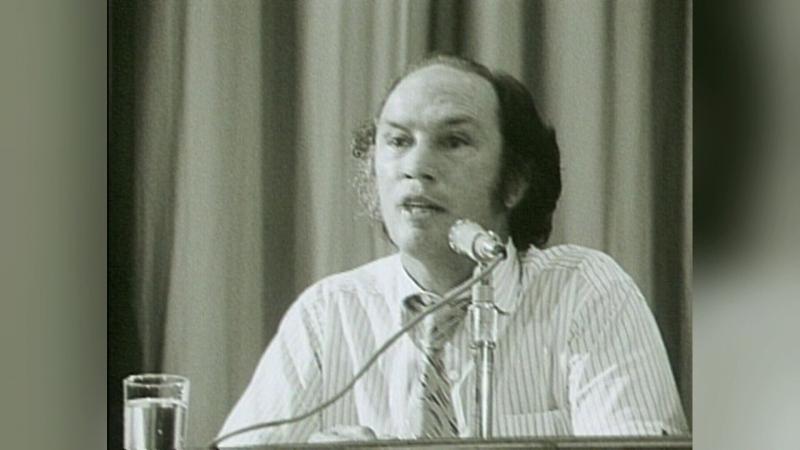

MONTREAL -- The announcement that Mayor Gerald Tremblay would halt all new municipal contracts is just part of the fallout from the testimony of one man: Lino Zambito.

In four days of at a public inquiry, the former construction boss has described an industry that operated as a tightly controlled, price-fixing cartel -- one where the Mob, local bureaucrats and even the mayor's political party allegedly took a cut.

He has dropped the names of some of the most powerful construction magnates, Mafiosi, and high-ranking ex-local officials -- all of whom have vigorously denied any wrongdoing.

And he hints that he's barely getting warmed up.

Zambito suggested this week that he is on the verge of exposing illicit practices outside Montreal and beyond municipal politics, although his testimony has not gone there yet.

For a change, while testifying Wednesday, Zambito focused on positive changes in the industry.

He said things started to clean up three years ago when the provincial government created an anti-corruption police unit -- nicknamed Operation Hammer. He said that instantly lessened a culture of bid-rigging and kickbacks and drastically reduced the price of public works in the province.

Pressed on how the police scrutiny changed the landscape, Zambito said the proof is in the price: He estimated that the cost of public-works projects dropped as much as 15 per cent.

"The best way to demonstrate it is to study the contracts," Zambito told commission chair France Charbonneau, who'd asked the question.

"I think that it shows that cost of contracts has gone down."

Zambito said the industry was scared straight in late 2009, following a series of shocking news reports that spurred the government to act.

He said that construction bosses were no longer being forced to pay so-called "taxes" and kickbacks to various people.

Zambito had previously testified that 2.5 per cent of the value of his rigged municipal contracts went to the Italian Mafia; three per cent went to the Montreal mayor's political party; one per cent was a bribe to a certain local bureaucrat; and many other gifts and cash went to other officials. All these things, along with industry collusion, pushed up the cost of construction work for years, he said.

But he said corrupt municipal engineers and bureaucrats suddenly started taking their retirement after the arrival of the Hammer squad -- and the extra fees stopped.

"Right there, the prices went down six or seven per cent," Zambito said.

Construction companies were concerned with the law-enforcement crackdown. He said collusion had gone on until at least August 2009, but declined after that.

Zambito said that by late October 2009, as the scandals erupted and the police pressure mounted, he personally refused to have anything to do with the cartel and even stopped taking phone calls from other bid-riggers.

From that point on, he said, he only participated in competitive bidding.

Zambito said that of the contracts he bid on after Oct. 22, 2009 -- when the Quebec government announced the police unit -- not a single one was rigged. But he said the traces of corruption lingered. Companies continued to stay inside the geographic boundaries they previously worked in, he said.

Quebec eventually introduced a permanent anti-corruption squad in 2011 that includes the Hammer unit.

Earlier Wednesday, Zambito said that while plenty of public-works contracts were rigged not everything was controlled by cartels.

Zambito said certain work, like contracts for bridges for example, was exempt because there wasn't a huge volume available.

"There wasn't enough work going to tender to warrant it," Zambito said, adding that any bridge work he had done was won competitively.

He said the cartel system extended to other areas of the industry like paving, sewers and sidewalks -- because those offered plenty of public money to go around and numerous jobs yearly.

Zambito, who is no longer in the construction business, said he thinks prices will eventually rise again as multinationals take over smaller- and medium-sized construction businesses.

"My vision of things is that in two or three years, the prices will artificially increase because the multinationals will control the market," Zambito said.

In 2011, Zambito's company went out of business. He was slapped with criminal charges and his company could no longer secure credit from the bank.

"The creation of the squad and my arrest left me on the outside in the industry," Zambito said.

A publication ban prevents media from reporting some details of Wednesday's testimony.