MONTREAL--The federal government has tossed in the towel and will stop fighting international efforts to list asbestos as a dangerous substance, striking another blow to a once-mighty Canadian industry now on the verge of extinction.

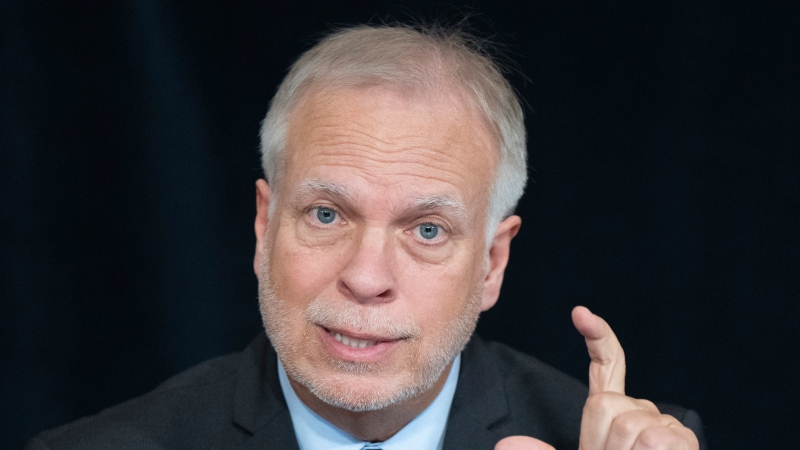

In a sudden reversal for the Harper government, Industry Minister Christian Paradis said Ottawa will no longer oppose efforts to include asbestos to the UN's Rotterdam treaty on hazardous materials.

For Paradis, the announcement Friday was far from celebratory.

He hails from central Quebec's asbestos belt and is one of the sector's staunchest defenders. Paradis looked glum and spoke in a nearly hushed tone as he spoke in his hometown of Thetford Mines, a community still dotted with imposing tailing piles that remind locals of the industry's once-bustling heyday.

He blamed the new Parti Quebecois provincial government for killing the industry and cast Friday's move as an inevitable response.

In making the announcement, the Conservatives fired the first shot in what is expected to be a turbulent relationship between Ottawa and the freshly elected PQ.

The PQ has said it will cancel a $58 million loan, confirmed just a few months ago by the previous Liberal provincial government. The cash was aimed at reviving what would be the country's only asbestos operation in Asbestos, a 90-minute drive from Thetford Mines.

Paradis took direct aim at the sovereigntist PQ and blamed it for the turn of events.

"First off I'd like to remind you that Pauline Marois, the premier-designate of Quebec, has clearly stated her intention to forbid chrysotile exploitation in Quebec," he said in his opening remarks.

"Obviously that decision will have a negative impact on the prosperity of our regions...

"In the meantime hundreds of workers in our region are without jobs, are living in uncertainty and hoping the mine will reopen... Madame Marois has clearly made her decision. So our government has made a decision that it's now time to look after our communities, workers and families."

The PQ said Friday that it had taken note of Paradis' announcement but would not react to it. The party also reaffirmed its commitment to hold a commission on the economic future of the industry.

Paradis promised that the Harper government would spend up to $50 million to help a region deeply in need of jobs diversify its economy. He made the announcement next to Thetford Mines Mayor Luc Berthold.

The mayor expressed disappointment about recent events and thanked the federal government for helping to make the best of a bad situation.

One industry official downplayed the significance of the announcement. Jeffrey Mine spokesman Guy Versailles said several other countries -- notably Russia, China and Brazil -- could still block the substance from being added to the UN list as they have in the past.

And even if does get listed, all that would mean is adding labels that warn about possible health risks and would not actually limit exports, he said.

"Inclusion of chrysotile in the Rotterdam Convention would in no way signal the end of the chrysotile business in Canada," Versailles said in an interview Friday.

"It does not say, 'prohibit imports and exports.' "

A bigger hurdle faced by Jeffrey Mine is the PQ campaign promise to cancel the $58-million loan to help revive the operation for another 25 years.

"I don't want to lack respect against politicians, but I must say that a company cannot govern itself according to declarations made during an election," Versailles said.

"This does not change the standing agreement we have with the Government of Quebec."

Canada gained a reputation as the world's top producer of the once-valuable global commodity that was hailed as the "magic mineral" for its fireproofing and insulating characteristics in construction materials.

But the asbestos sector's profitability has been pummelled by bad publicity over the years. Health experts and human-rights advocates have frequently voiced concerns about the substance, pointing to studies that have shown inhaling needle-like asbestos fibres can lead to diseases such as lung cancer.

The World Health Organization estimates that 107,000 people die globally each year from asbestos-related disease.

As a result, Canada's asbestos sector ground to a halt last fall for the first time in 130 years when production stalled in both of the country's mines -- one in Thetford Mines and the other in Asbestos.

Persistent health warnings have slowly eroded support for asbestos mining and exports, including within the Conservative caucus.

Several Tories took the unusual step of questioning their government's policy on asbestos exports last year.

Industry experts were independently invited to a meeting on Parliament Hill, where about a dozen Conservative MPs asked some pointed questions of the Chrysotile Institute and industry scientists over several hours.

The meetings revealed that a clear divide over the Tory government's resistance to having the substance listed as a hazardous substance internationally. It was a rare public hint of internal dissent from a caucus known for its tight discipline.

Former Conservative cabinet minister Chuck Strahl had been a longtime advocate for listing asbestos in the Rotterdam Convention.

Strahl contracted a form of cancer his doctors say was related to asbestos exposure while working in the B.C. logging industry as a young man.

"It's the moral thing to do," Strahl said Friday in an interview.

"We say this is the warning, this is what we know, if you're going to use this stuff, be warned.

"By not listing it under the Rotterdam Convention, we don't even tell people that. And that's wrong. Where the government's headed now is the right thing to do. List it, I think there'll be a very small number of countries that say that they still want to use it once it's listed."

The Conservatives and other defenders of the asbestos sector have long maintained that the substance, especially the chrysotile form mined in Quebec, can be safe if handled properly.

But the industry's critics say they doubt that the mainly poor countries that import Canadian chrysotile can offer such safety guarantees.

The Canadian Public Health Association lauded Paradis' announcement, noting that Canada was among only a handful of countries -- including Zimbabwe, Russia and China -- that helped block chrysotile's listing as a hazardous substance in the Rotterdam Convention.

"Canada has a moral obligation, backed by well-grounded evidence, to close down this industry and stop exporting a potentially hazardous material to countries that are ill-equipped to protect the health of workers who handle asbestos and people exposed to asbestos fibres," Erica Di Ruggiero, the association's chair, said in a statement.

"The Government of Canada has made a good 'public health' decision."

--with a file from Jennifer Ditchburn in Ottawa.