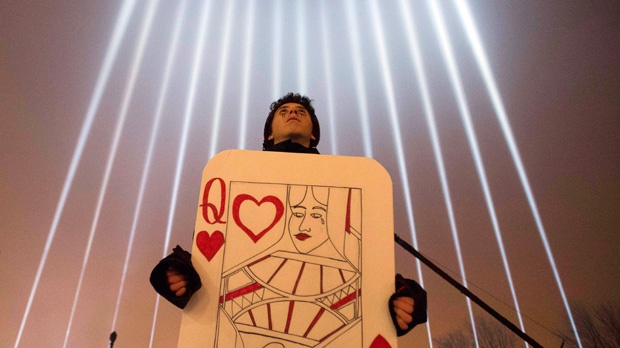

MONTREAL -- Thirty years after the worst mass shooting in Canadian history, official acknowledgment has come that what happened on Dec. 6, 1989 at Montreal's Ecole Polytechnique was an attack on feminists.

On the eve of Friday's anniversary, Montreal changed a plaque in a memorial park that previously referred to a "tragic event" -- with no mention that the victims were all women. The revised text unveiled on Thursday describes an "anti-feminist attack" that claimed the lives of 14 women.

"I think it's a very good thing, but in a way, I understand why it took so long," said Catherine Bergeron, who lost her sister, Genevieve, on that day in 1989. "The event was such a shock and so dramatic that it was hard to admit the real origins of it until today."

Thirty years on, questions continue to swirl about gun control, and violence and discrimination against women persist. Just last year, the man accused of using a rented van to kill 10 people and injure 16 others last year in Toronto told police the attack was a day of retribution because women sexually rejected and ridiculed him.

Nathalie Provost, who was shot four times in the Polytechnique attack, said using the right words to describe the Polytechnique shootings is crucial.

"I think it's very important to bear witness to reality. It was an anti-feminist act. It was obvious from the moment it happened," Provost said. "I think that for those who will go there and take the time to read it, they'll better understand what happened exactly on that horrible day. And that's important for the memory of my friends."

Claire-Anse Saint-Eloi, who is overseeing a Quebec Women's Federation campaign to end violence against women, said identifying the attack as one against feminists opens the way to addressing ongoing problems.

Three decades later, she said, victims of sexual violence, victims of discriminatory laws and victims of racism still struggle to be believed. "But when we name the violence, we can say what do we next?" she said.

Bergeron, who is head of the committee organizing this year's commemorative events, said there will be a focus on the lives behind the names.

Those names are well-known and each year they are read out: Genevieve Bergeron, Helene Colgan, Nathalie Croteau, Barbara Daigneault, Anne-Marie Edward, Maud Haviernick, Barbara Klucznik-Widajewicz, Maryse Laganiere, Maryse Leclair, Anne-Marie Lemay, Sonia Pelletier, Michele Richard, Annie St-Arneault and Annie Turcotte.

"We know their names," Bergeron said. "For the past 30 years, we've said them, reminding people that they were women, but who were they? What were their hopes? Where did they want to be?"

A new book written by former Le Devoir editor Josee Boileau looks closely at the events and the victims themselves. Commissioned by the organizing committee, the idea was to give the next generation a reference but also remind that the women were more than victims.

"They were all very talented in a lot of fields. They were very energetic and nice and kind," Bergeron said. "They were women that were curious to try different things -- they were rays of sunshine in their respective families -- that's what comes out."

Provost was a 23-year-old engineering student when Mark Lepine singled out women during his 20-minute shooting rampage. Fourteen women were killed -- mostly students -- while 13 people were wounded -- nine women and four men.

In a classroom, Provost came face-to-face with Lepine, armed with a .223-calibre Sturm-Ruger rifle. The shooter made clear he was targeting his victims because he saw them as feminists -- people he blamed for his own failings. Provost survived being shot in the forehead, both legs and a foot.

On the 30th anniversary, Provost said she looks at the harrowing events in a different light now that her own children are around the same age she was at the time.

"I more fully realize how young I was -- I was a kid and we were kids -- and it moves me a lot to see my kids and see they are where I was in my life -- at the beginning," she said. "I'm also much more sensitive to how terrible the loss of a child might have been for the families who had to survive after their kids (were killed) -- I cannot imagine my grief and I don't want to imagine it."

Serge St-Arneault, whose sister Annie was killed that day, views the anniversary as a chance to come to terms with the tragedy.

"We finally found the word that was missing -- femicide -- it was women who were targeted," he said.

St-Arneault was halfway across the world in 1989 doing missionary work at the Congo-Uganda border, and it took him a month to get back home. He was close to his sister -- one of four siblings -- and in the years that have passed, he has fought for tougher gun laws and an end to violence against women as a way of honouring Annie's memory.

"There was before Dec. 6, 1989, and after," St-Arneault said. "This moment is a pivotal one in Quebec and Canada, that we must mobilize to build a society where women are safe."

But for survivors and victims' families, the fact the weapon used in the mass killing has yet to be banned by Canadian authorities is difficult to fathom.

"It's not easy, especially for the families, to keep fighting after 30 years, to keep facing the fact that the weapon that was used to kill their sisters and daughters is still legal and non-restricted," said Heidi Rathjen, who was a Polytechnique student the night of the shooting and later became a staunch gun-control advocate.

Rathjen says they want to see "comprehensive, bold gun-control measures," from the re-elected federal Liberals, including a full ban on assault-style weapons and handguns in short order. She pointed to New Zealand, which brought in a ban on assault weapons and rigorous screening and registration measures after a mass shooting at two mosques claimed 51 lives last March.

"If the new government doesn't act decisively and boldly in the public interest now, 30 years later, after having been elected twice on the basis of a promise to strengthen gun control, then when?" Rathjen asked.

-This report by The Canadian Press was first published on Dec. 5, 2019.