With one hand on the Bible, or clutching a traditional eagle feather, they take a solemn oath: we’re here to tell the truth – the whole truth, and nothing but.

For the next five days, dozens of First Nations community members will give their testimony and recount stories of loved ones lost to circumstance, or violence.

These are the first hearings to be held in Quebec as part of the Federal inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) since commissioners visited the Maliotenam Reserve on the Cote-Nord.

Since its launch in September 2016, the inquiry has amassed 700 separate stories about women who either disappeared or became victims of homicide; among them, mothers, daughters, sisters, and friends.

The inquiry is expecting to collect 600 more statements as it moves through the country.

Last week, an additional two years and $50 million were requested from the Canadian government to extend the commission’s mandate. Once testimonies are documented, the hope is that the Canadian government will develop, implement, and improve policies and increase accountability for systemic discrimination.

At the same time, the hearings provide an outlet to honour Indigenous lives and legacies, and promote healing.

“It’s nuanced everywhere we go: the realities, the discrimination, the difficulties and challenges, and different impacts of colonialization on individuals and communities throughout the country,” explained Qajaq Robinson, a lawyer and one of five MMIWG commissioners overseeing the inquiry.

Aboriginal women are five times more likely to die a violent death than other women: between 1997 and 2000, the homicide rate among Indigenous women was seven times higher than among non-Indigenous women.

Of the 582 cases examined by the Native Women’s Association of Canada, 67 per cent are murder cases – and nearly half of them unsolved.

The issue impacts women and girls across Aboriginal communities: First Nations, Metis, and Inuit.

This is one of their stories.

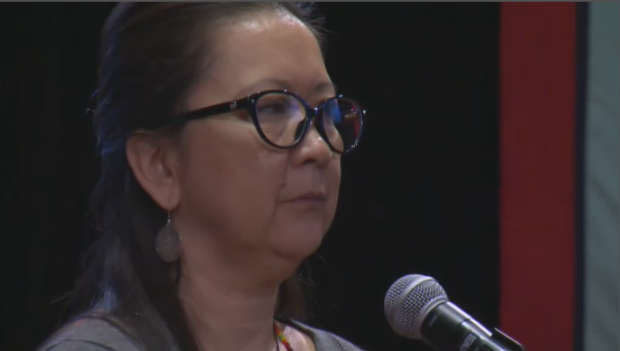

Cheryl McDonald, Mohawk - speaking for sister Carleen McDonald

"One day, this will all be worth it - talking my truth about losing my sister to violence. Physical, emotional - it played out everywhere. We met it at home. We probably heard it in our mother's womb."

These are the details, as Cheryl McDonald gave them.

Carleen McDonald was a rambunctious spirit – defiant even. She hated dresses, was a “rough tomboy” who egged on her younger sister Cheryl – threatening to cut the hair off her dolls if she ever found them.

Young Carleen drove her parents crazy, but could make them laugh. If you asked her to climb down from the kitchen table at home in Malone, NY, she'd refuse. Cheryl says that once, her rough-and-tumble sister went around the house not knowing or caring that a fly sticker had become tangled in her thick, long hair.

The sisters would grow up, and apart. Carleen fell in love with an Army man and gave birth to her first child at 16.

After years of a common-law union, in 1988, Carleen would separate from the “love of her life,” and move in with her parents and three children— at the time, all under the age of ten.

The house at the end of the road was small, so Carleen stayed in the basement. It was bordered by a field, and lush woods.

One day, as she did groceries with her mother, Carleen purchased a bottle of rum, and insisted the family go out on the river. She made some calls – one to her sister Cheryl, who was aware of some residual sadness lingering after the separation. They chatted, Carleen inquiring about her sister’s life.

They hadn’t been close for a while, and for that reason, Cheryl remembers the phone call clearly.

What’s unclear are the circumstances that prompted her older sister Carleen to slip out of the house while her parents and children were asleep on the morning of September 4.

“What was she thinking? Why did she leave us all? Why did she leave her children? Why did she leave my parents?” After 30 years, the questions still surface in Cheryl’s mind.

Carleen, 25, never returned.

“I could just tell by the clouds, how dark and heavy they were,” Cheryl said. Her instinct said that something was wrong.

The family consulted with psychics and clairvoyants, each with a different version of what happened to Carleen.

Buzzards and helicopters circled the air over the woods where the Akwesasne police force would search briefly later on.

Tips placed with police, Cheryl says, went unanswered, or weren’t treated seriously.

Despite pleading with police to search the woods and the area around the house, there was no trace of Carleen.

Seven weeks after her disappearance, it was a deer hunter who stumbled upon Carleen’s skeletonized remains in the woods adjacent to the house she shared with her parents.

The bones were pulled from the forest, and immediately sent in an ambulance to the coroner's bureau in Valleyfield, Cheryl says.

At the time, the McDonald family was told by police that there wasn’t enough flesh left on the bones to extract viable DNA samples. Carleen’s remains would only be identified later on by orthodontist records.

Days after the discovery, together, the family trekked out into the woods where the bones were found. On the forest floor, they found a dirty blanket and the remnants of a human scalp – a tangle of thick, long hair.

“They left her hair – they left the crime scene. They left us to watch and pick up her hair like it was a dirty wig, and just drop it on the ground,” Cheryl explained. “Her hair could’ve been tested. I know police don’t get a lot of funding – why didn’t they call another police agency?”

Carleen’s ex-partner was questioned, telling police she’d disappeared before, was a drinker, and liked to party. He was the last person to speak to Carleen before she disappeared, but quickly ruled out as a suspect.

Cheryl says she’s grappled with possibilities for nearly 30 years, and is unable to say whether an abusive partner played a role in her death.

“For 27 years I would go from suicide, to ‘someone did this,’ or ‘it was the only way out, she was in trouble’ or ‘he did it – or he knew about it,’ then suicide. And so I went through this constant churning. Then set it aside,” she said.

But Cheryl is aware there may never be a resolution in her sister’s case. She doesn’t blame the underfunded Akwesasne-Mohawk police, but she says the family needed more help to find Carleen.

“If they had the services to find her, like the do in the cases of non-Indigenous women in the cities, maybe my sister would have been found in an alcoholic coma,” she said.

She’s buried in a grave marked with a simple cross in Akwesasne. The family never bought a tombstone, or visited the grave after the fact – except for Cheryl.

“We have to feel to heal, and I’ll tell you, I cried a lot,” she said.

But the healing process really began when the commission was announced and other stories of women with similar, lingering pain were shared openly. Cheryl says they all endure the same struggle, the same pain and trauma.

“It’s stronger than us. I can’t argue with the word for that love, that energy that unites us all together,” she said.

Right now, Cheryl says it feels right to share the grief with everyone.

“I want this to go into the schools, I want the youth to be listening to this, I want parents to listen to these families,” she explained.

“It’s like I was meant to end one life, and begin another – and this one is on my terms.”

This testimony is the first of 71 that will be heard this week during Montreal's hearings at Place Bonaventure.

For more information regarding the Commission on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, visit their website: http://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/