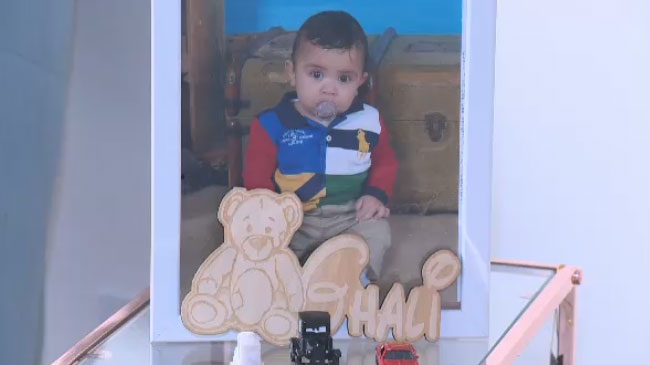

The parents of a 23-month-old boy are searching for answers after a tragic mistake in Ste-Justine Hospital led to the death of their only child.

His mother, Hadil El Amrani, described her son Ghali as “a wonderful little guy. So quiet, so nice. He was just a perfect little baby.”

In June, Ghali was diagnosed with neuroblastoma, a form of cancer that had spread to his bone marrow. He underwent six rounds of chemotherapy followed by a bone marrow transplant. After that procedure, he was recovering in hospital when a doctor prescribed him a shot of potassium.

El Amrani said a nurse came into his room with two syringes – one was supposed to be for the potassium and one filled with saline. But soon, it became evident that a serious mistake had been made. Both syringes has been filled with potassium, leading the boy to enter cardiac arrest. He would suffer four heart attacks as medical workers scrambled to save him.

“They tried, many times, to resuscitate him. He came back after 25 minutes,” said El Amrani. “He was transferred to another department and he unfortunately had three heart attacks before the last one.”

In a preliminary report, the coroner states as a probable cause of death that the child received care for a neuroblastoma in which a solution of potassium and phosphate was administered by mistake.

Ste-Justine admits that the medication did play a role in the child’s death, but say that at his stage of the illness, they cannot place blame on any member of the care team.

The family’s attorney, Jean-Pierre Menard, said incidents where syringes get mixed up should never happen if proper protocols are being followed.

“The nurses are trained to follow (a procedure) for each medication,” he said. “When they are administering dangerous medications like potassium, the protocol is very, very strict about verification and preparation.”

Menard said mix-ups like this are far too common.

“Every year, we're leaning towards about five to 10 cases of medication error that have caused death or serious physical impairment to a patient,” he said.

El Amrani said that while doctors immediately acknowledged a mistake had been made, her and her family have yet to receive an apology or explanation from the hospital.

“The nurse couldn’t remember what she did. She had witnesses to say she did the right job but we still have the question, why did it happen?” she said.

Patients’ rights advocate Paul Brunet said that mistakes such as the one that led to Ghali’s death are not unheard of in a busy medical system like Quebec’s, but that it’s important for administrators and hospital workers to admit fault to help grieving families.

“As long as you have humans giving healthcare to other humans, you will have that human factor,” he said. “But what caused it? Is this a mistake, a distraction, is it because there were a lot of cases that human had to take care of?”

“I always want the administration to go towards the family and say we’re sorry,” he added. “That should be the first thing we do but sometimes we’re a little shy and that does not help to give the system a human face, especially in those cases.”

El Amrani and her family have not yet filed a lawsuit against the hospital but are in the early stages of making a claim. But more than any financial compensation, she said wants answers and to know what happened to her son will never happen again.

“It’s very important for other parents to know what happens in the hospitals,” she said. “It’s happened before but parents decided not to talk about it. My son was the second case in Ste-Justine. I hope it’s going to be the last one.”

With a report from CTV Montreal's Aalia Adam