Scores of aboriginals from across Ontario rallied in Toronto today ahead of a landmark court hearing on the so-called '60s Scoop.

Some travelled for up to two days to lend their support.

Speakers, including the lead plaintiff, denounced what they view as the "cultural genocide" perpetrated against them by the Canadian government.

They mourned the loss of their "stolen" children and urged the government to make good on its promise of a new era in Canadian-aboriginal relations.

At issue is the apprehension of indigenous children by child-welfare officials, who placed the young wards with non-native families.

Speakers said the practice was a deliberate effort to assimilate aboriginal children.

The $1.3-billion class action argues that Canada failed to protect the children's cultural heritage with devastating consequences to victims. Their lawyers are pressing for summary judgment in the legal battle started in February 2009.

The '60s Scoop depended on a federal-provincial arrangement in which Ontario child welfare services placed as many as 16,000 aboriginal children with non-native families from December 1965 to December 1984.

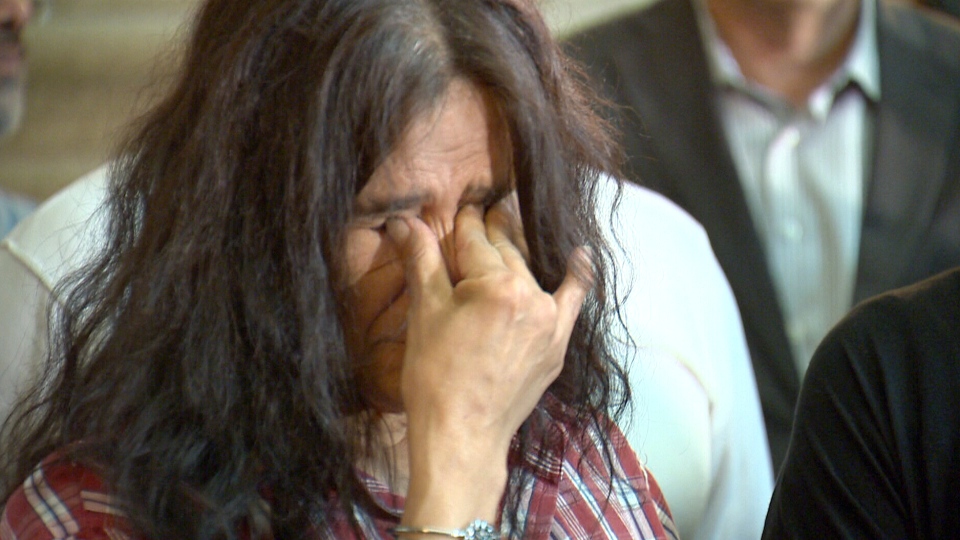

Lead plaintiff, Marcia Brown Martel, a member of the Temagami First Nation near Kirkland Lake, Ont., was taken by child welfare officials and adopted by a non-native family as a child. She later discovered the Canadian government had declared her original identity dead.

The unproven claim alleges the children suffered a devastating loss of cultural identity that Canada negligently failed to protect. The children, the suit states, suffered emotional, psychological and spiritual harm from the lost connection to their aboriginal heritage. They want $85,000 for each affected person.

Their lawyer, Jeffery Wilson, called the lawsuit the first case in the western world about "whether a state government has an obligation to take steps to protect and preserve the cultural identity of its indigenous people."

The motion for summary judgment essentially calls on Superior Court Justice Edward Belobaba to decide the case based on the evidence the court already has without a full trial.

Canada has tried on several occasions to have the case thrown out as futile. Among other things, Ottawa argues it was acting in the best interests of the children and within the social norms of the day.

The one-day hearing was expected to adjourn until Dec. 1 to allow the government time to file its expert evidence.

Last week, Indigenous Affairs Minister Carolyn Bennett said she would like to see the case discussed at the table rather than in court.