Quebec has done 'very little' for Indigenous academic success: auditor general

Quebec’s Education Ministry has done little to promote the academic success of Indigenous students; there is a lack of funding and no guiding strategy for schools, according to the auditor general’s latest report.

The gap in success rates of Indigenous students was first flagged 20 years ago, and since then the ministry has done “little to help them succeed,” said the report published Wednesday. It identified systemic barriers like a lack of linguistic support and culturally relevant learning environments.

Many Indigenous students start their education in their own communities and later change into Quebec’s education system. According to the auditor general, of 31 First Nations communities (other than Cree and Naskapi), 23 have a school, and secondary education isn’t fully offered in eight of them.

But the students aren’t properly supported during the transition, said the 57-page report.

“Indigenous students do not receive sufficient support, nor is it adapted to their needs, when they transition from a school in their communities to one in the Quebec school system. Nor do they receive enough help in French,” said the report.

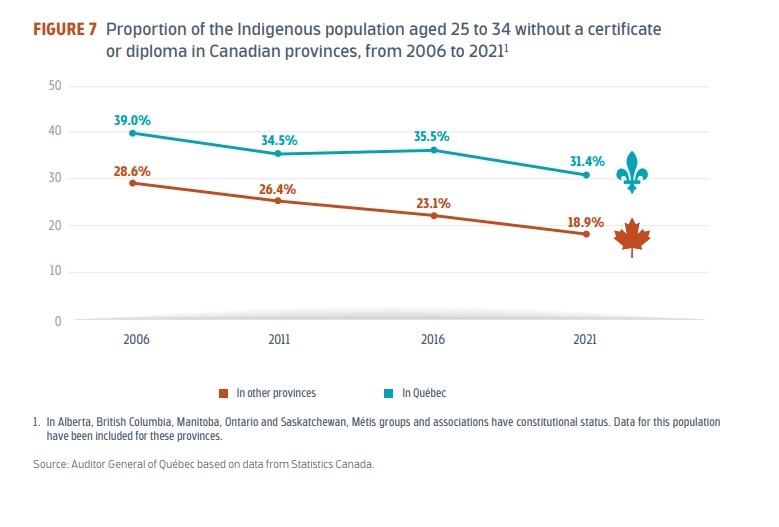

As a result, Indigenous students in Quebec have the highest drop-out rates compared to those elsewhere in Canada. As of 2021, about 31 per cent of Indigenous people studying in Quebec don’t have a diploma or certificate, compared to about 19 per cent in the rest of Canada.

“[The Education Ministry] is not doing enough. They must do more. They must do better. They must do differently,” said Sébastien Simard, the audit director for the report.

He pointed out that the report includes nine recommendations like providing the school system with tools and solutions adapted to the needs of Indigenous students, integrating of Indigenous realities into curriculums, evaluating funding methods and training staff to avoid prejudice.

“We need to do better to make sure that Indigenous students feel safe and it's a good learning environment for them,” said Simard.

More funding for immigrants learning French

Denis Gros-Louis, head of the First Nations Education Council (FNEC), said he welcomed the report and sees opportunities for the FNEC and the Education Ministry to work together to overcome barriers for students.

“There's a disconnect about our realities from the Ministry of Education,” said Gros-Louis.

He said he was shocked to find out that the government is the “stark inequity” in funding for Indigenous students compared to immigrants when it comes to teaching French. The report notes that the allowance to support Indigenous students learning French is $450 per student, per school year. In comparison, $6,813 is allocated for students from immigrant backgrounds when they first enroll. There is no support for students in English schools.

Gros-Louis pointed out that most Indigenous students have a first language that isn’t French or English, and knowing French is typically a requirement to get into English universities.

“You're being forced to speak the colonial languages in order to graduate ... You speak your own language, you go to McGill University, you speak English, then you're assessed. You're asked to be fluent in French as well, which is the third language to us,” he said.

“It's a systemic barrier to success.”

Indigenous people in Quebec have lower graduation rates than those elsewhere in Canada. (Auditor General of Quebec)

Indigenous people in Quebec have lower graduation rates than those elsewhere in Canada. (Auditor General of Quebec)

The education minister should discuss the report at the Table for First Nation and Inuit Success and implement their recommendations, identify timelines and develop a working plan,” said Gros-Louis.

“That's when we will bring back the trust between the ministry and First Nation organizations,” said Gros-Louis.

“They don't know our First Nation students, they don't know our schools, they don't know our needs, and it's clearly highlighted in the report … We have that expertise.”

The report mentioned initiatives from other provinces, like in British Columbia where students must complete four credits in Indigenous-focused coursework to graduate from high school. Manitoba’s Education Ministry has tools to incorporate Indigenous perspectives in its curriculums and emphasized its teaching of residential schools’ history.

Allocation of funds

The education ministry said it acknowledged the report and agreed with some findings, but it considers that “although adjustments are necessary” it implemented “actions in favour of Indigenous students.”

When asked about the report by journalists at the National Assembly, the Minister Responsible for Relations with the First Nations and the Inuit, Ian Lafrenière, defended his government’s past investments.

“Am I concerned? Yes. Is education important? Absolutely. Have we been investing into it? Also absolutely,” he said.

But part of the report said the money isn’t “allocated on the basis of regional needs and realities, and the funding methods do not allow for the implementation of sustainable actions.”

The ministry has to set objectives and targets for the success of Indigenous students, “as it has done for other groups of students in which it identified a gap in success rates,” said the report.

“We traveled around Quebec to do this report. We have met well-intentioned people. We have met engaged people that put in place promising initiatives, but they just remain local,” said Simard.

“The main goal is to have a vision and put in place a strategy and a framework — guidelines to help everyone.”

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Richard Perry, record producer behind 'You're So Vain' and other hits, dies at 82

Richard Perry, a hitmaking record producer with a flair for both standards and contemporary sounds whose many successes included Carly Simon’s 'You’re So Vain,' Rod Stewart’s 'The Great American Songbook' series and a Ringo Starr album featuring all four Beatles, died Tuesday. He was 82.

Hong Kong police issue arrest warrants and bounties for six activists including two Canadians

Hong Kong police on Tuesday announced a fresh round of arrest warrants for six activists based overseas, with bounties set at $1 million Hong Kong dollars for information leading to their arrests.

Read Trudeau's Christmas message

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau issued his Christmas message on Tuesday. Here is his message in full.

Stunning photos show lava erupting from Hawaii's Kilauea volcano

One of the world's most active volcanoes spewed lava into the air for a second straight day on Tuesday.

Indigenous family faced discrimination in North Bay, Ont., when they were kicked off transit bus

Ontario's Human Rights Tribunal has awarded members of an Indigenous family in North Bay $15,000 each after it ruled they were victims of discrimination.

What is flagpoling? A new ban on the practice is starting to take effect

Immigration measures announced as part of Canada's border response to president-elect Donald Trump's 25 per cent tariff threat are starting to be implemented, beginning with a ban on what's known as 'flagpoling.'

Dismiss Trump taunts, expert says after 'churlish' social media posts about Canada

U.S. president-elect Donald Trump and those in his corner continue to send out strong messages about Canada.

Heavy travel day starts with brief grounding of all American Airlines flights

American Airlines briefly grounded flights nationwide Tuesday because of a technical problem just as the Christmas travel season kicked into overdrive and winter weather threatened more potential problems for those planning to fly or drive.

King Charles III is set to focus on healthcare workers in his traditional Christmas message

King Charles III is expected to use his annual Christmas message to highlight health workers, at the end of a year in which both he and the Princess of Wales were diagnosed with cancer.