Evan Prescott, eight, scoots around his house on his knees to spare himself pain.

As a newborn, Evan quickly developed blisters all over his body. He spent the first six months of his life swaddled in bandages.

“His hands, his fingers had to be individually wrapped—his toes, everything had to be separated,” said Yandy Macabuag, Evan’s mother.

Shortly after came a shocking diagnosis: their infant son had a form of epidermolysis bullosa, a lifelong condition that would mar his small body with blisters and open wounds.

It's a rare genetic abnormality that causes the skin to blister easily, but it is not hereditary -- neither of Evan's parents have the same condition. It can be especially fatal during a child's first year of life because of the high risk of infection.

His parents were afraid to touch him. Evan stayed in the hospital for months, where a complex care team ministered to his skincare needs.

But once at home, his parents had to take over a twice daily, grueling regimen.

“He’s lying down and basically we check him for blisters, and any blisters that he has, we have to lance,” Macabuag explained. “We pop them with a sterile needle that we have a prescription for, and we drain them.”

The process is only further complicated by the very real, sometimes imminent threat of infection. Evan takes salt baths every two days to dry out the skin and minimize the risk of complications.

But his condition was still difficult to accept in their home, especially because of the pain Evan felt while being checked over by his parents.

His mother says he would just “cry and cry and cry” before communicating coherently with words during the daily examinations.

“As a parent, it’s horrible, because you’re told that you’re doing this to help your child-- and you feel like this monster who’s attacking them,” she said.

About 75 per cent of the time, Evan moves about on his knees to keep the pain at bay. At school, he mobilizes using a wheelchair.

The family's medical team tested every standard treatment on Evan – from opioids to distraction techniques—but nothing worked. But one physician, a chronic pain specialist, refused to give up.

“You see suffering in the face of the kid who cannot walk, and you see suffering in the face of the mother that has to inflict pain,” explained Dr. Pablo Ingelmo, who works out of the Montreal Children’s Hospital.

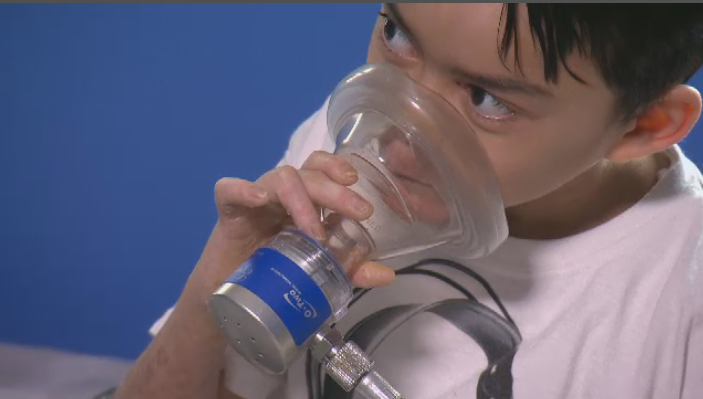

He assembled a team and came up with a novel ideal for treatment: nitrous oxide, better known to some as “laughing gas.”

It responded to the family’s needs, it was fast-acting, with no lingering side effects – perfect for a young, developing child like Evan, doctors concluded.

He became the first child in the world – part of the first family in the world – to be trained to use nitrous oxide at home. The positive results, his mother said, have been “life-changing.”

“It lifted a lot of pressure, right – my son doesn’t have to have tears to do this,” Macabuag said.

Knowing that there is some relief to his chronic pain, Evan’s burgeoning confidence and diminished anxiety have led him to do great things – like running.

Evan trained for months with friends before completing, and winning, two 50-metre races.

Evan’s mother said she hopes the continued chronic pain research now underway at the Montreal Children’s Hospital will open up the same world of possibilities for other sick children as well.