'I can't see anything': a rare condition that causes sudden blindness and a Montreal study that could help

When Brett Murphy developed a searing migraine one day in 2017, the busy professional and father of two young boys blamed it on fatigue.

He could never have predicted that within a week he would lose his vision entirely, then regain his sight after treatment, and suffer from relapses over the ensuing years.

And, now at 41, Murphy, who lives west of Montreal, is also eager to help get the word out about a study that Montreal scientists are involved in that is testing a drug they hope will quell the condition, and halt the potential for permanent blindness over time.

Back at the age of 35, he was otherwise healthy and didn't suspect his symptoms were anything serious until he realized the headaches weren't going away. By the third day, in terrible pain, he started to see "little weird spots," and decided it was time to go to a general hospital for help.

Doctors ordered a slew of tests, performed a spinal tap and ruled out a brain tumour but they could not come up with a diagnosis.

Murphy was admitted. They performed more tests, tried to treat his pain and observe him. They checked to see if he'd suffered a stroke and put him in isolation in case he'd caught a contagious virus of some kind.

It turns out Murphy was in for a terrible shock.

"I woke up in the morning to the nurse taking my vitals and I could feel the blood pressure cuff on and I said oh, it's okay, you can turn the lights on. And they turn the lights on and nothing changed. And I realized at that point like oh wow, I can't see anything," said Murphy.

"I didn't know if I was ever going to be able to see my kids again," who were three and one year old at the time, he said as he described the devastation and panic he experienced. Brett Murphy with his two boys, two and one year old in 2017, just before his first episode of MOGAD, a neurological disease. Submitted photo

Brett Murphy with his two boys, two and one year old in 2017, just before his first episode of MOGAD, a neurological disease. Submitted photo

DRAMATIC CASE

He was immediately transferred to the Montreal Neurological Institute for expert care.

The neurologist and multiple sclerosis (MS) clinic director who was treating him that day remembers their first encounter well because of the "striking presentation" of symptoms.

"We see patients all the time in the MS clinic and when patients present to the hospital and are admitted on the ward we see a lot of dramatic episodes of neurological dysfunction," explained Dr. Paul Giocomini.

But the case before him was unusual even for an MS patient - which Murphy was not.

"It was very intense and dramatic and involved both eyes and the speed with which he lost his vision was quite stunning. And this is one of the red flags that made us think that this could be another kind of neuroinflammatory disorder." Brett Murphy and his wife Kaitlyn Moss at the Montreal Neurological Institute, shortly after he lost his vision. Submitted photo

Brett Murphy and his wife Kaitlyn Moss at the Montreal Neurological Institute, shortly after he lost his vision. Submitted photo

The tell-tale sign Giocomini said, was the way both optic nerves were affected at the same time, or sequentially. That occurrence made a diagnosis of MS less likely.

Instead, the medical team suspected Murphy had Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Associated Disease (MOGAD), a rare demyelinating disease affecting the optic nerve, spinal cord and brain.

MOGAD OFTEN MISTAKEN FOR MS

It's a rare illness. A Quebec registry shows it only affects about 60 people in Quebec though it's likely other patients may not know they have it since the condition is similar to an inflammation of the optic nerve that is a common early symptom of multiple sclerosis.

"Patients like Brett who have this illness, they can sometimes get mistaken for MS and it's important to sort of make that distinction because the treatments for MS don't necessarily work for MOGAD," he said -- even though MOGAD is considered to be in the MS family.

The disease is relapsing-remitting which means that patients can go through long periods of wellness and stability without having any symptoms.

"And that can be falsely reassuring because these attacks can recur," said Giocomini. "And with each subsequent episode, even when treated aggressively, there's always the risk of permanent visual loss or permanent neurological damage."

Doctors decided to start treating Murphy for MOGAD right away with high doses of corticosteroids over several weeks, while they waited the several weeks it would take to get the results of a confirmatory antibody test.

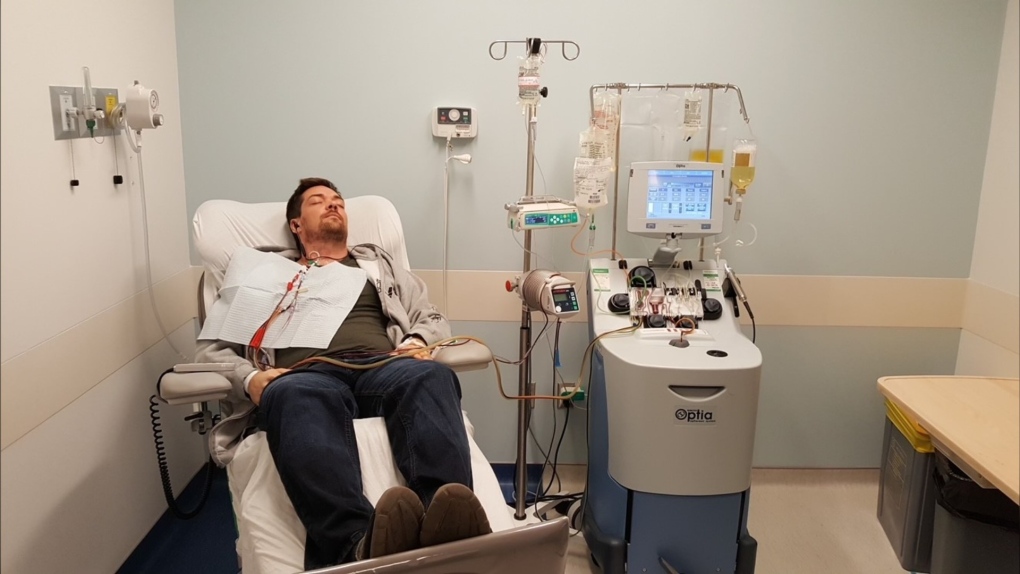

"We also combine that with a treatment called plasmapheresis, which is like filtration of the blood, similar in some respects to dialysis, but to filter out the antibodies that are important and causing the disease," Giocomini said. Brett Murphy was treated at the Montreal Neurological Institute after his first episode of MOGAD. The condition caused complete vision loss, which the treatments restored. Submitted photo

Brett Murphy was treated at the Montreal Neurological Institute after his first episode of MOGAD. The condition caused complete vision loss, which the treatments restored. Submitted photo

Slowly but surely, the treatments began to work and the darkness started to lift for Murphy

"I woke up one morning and I can see the outline of these lights on the ceiling. Oh my gosh, it's actually working," said Murphy, recalling his reaction at the time.

'I COULD BE PERMANENTLY BLIND'

The antibody test confirmed the diagnosis. The pieces of the puzzle had fallen into place. But in some ways, the battle was just beginning for Murphy and his doctors.

He's had two additional episodes of MOGAD since then and had had to rush to emergency rooms each time the symptoms begin. His vision has been restored, but his optic nerves get damaged each time.

And the corticosteroid treatments, which doctors are now giving him preventatively on occasion to try and suppress attacks, are unreliable and have long-term side effects.

There is hope, however, that a new study will be able to help determine if there's a treatment out there to quash any new episodes.

"We're part of a multicentre international study that's evaluating an existing monoclonal antibody therapy that's been used in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, a related condition," Giocomini said.

"This therapy targets inflammatory messengers, and this mechanism of treatment has actually been used in other inflammatory illnesses, like rheumatoid arthritis, for many years," he said.

People who have been diagnosed with MOGAD are advised to speak to their doctor if they would like to participate in the trial to see if they meet the study criteria.

Since Murphy is now in remission, he does not meet the criteria, but he is hoping others will step forward to help a community of sufferers get more answers.

"I could be blind and permanently blind. I could lose colours, or I may never be able to drive a car again. So to have access to a medication that would be designed specifically to treat this disease would be a game changer," he said.

Murphy said pharmaceutical companies aren't always around when it comes to providing treatments for people with a rare condition, "but it still does affect people and it has a major impact."

"It takes studies like this and trials like this to make those medications available."

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Donald Trump says he urged Wayne Gretzky to run for prime minister in Christmas visit

U.S. president-elect Donald Trump says he told Canadian hockey legend Wayne Gretzky he should run for prime minister during a Christmas visit but adds that the athlete declined interest in politics.

Historical mysteries solved by science in 2024

This year, scientists were able to pull back the curtain on mysteries surrounding figures across history, both known and unknown, to reveal more about their unique stories.

King Charles III focuses Christmas message on healthcare workers in year marked by royal illnesses

King Charles III used his annual Christmas message Wednesday to hail the selflessness of those who have cared for him and the Princess of Wales this year, after both were diagnosed with cancer.

Mother-daughter duo pursuing university dreams at the same time

For one University of Windsor student, what is typically a chance to gain independence from her parents has become a chance to spend more time with her biggest cheerleader — her mom.

Thousands without power on Christmas as winds, rain continue in B.C. coastal areas

Thousands of people in British Columbia are without power on Christmas Day as ongoing rainfall and strong winds collapse power lines, disrupt travel and toss around holiday decorations.

Ho! Ho! HOLY that's cold! Montreal boogie boarder in Santa suit hits St. Lawrence waters

Montreal body surfer Carlos Hebert-Plante boogie boards all year round, and donned a Santa Claus suit to hit the water on Christmas Day in -14 degree Celsius weather.

Canadian activist accuses Hong Kong of meddling, but is proud of reward for arrest

A Vancouver-based activist is accusing Hong Kong authorities of meddling in Canada’s internal affairs after police in the Chinese territory issued a warrant for his arrest.

New York taxi driver hits 6 pedestrians, 3 taken to hospital, police say

A taxicab hit six pedestrians in midtown Manhattan on Wednesday, police said, with three people — including a 9-year-old boy — transported to hospitals for their injuries.

Azerbaijani airliner crashes in Kazakhstan, killing 38 with 29 survivors, officials say

An Azerbaijani airliner with 67 people onboard crashed Wednesday near the Kazakhstani city of Aktau, killing 38 people and leaving 29 survivors, a Kazakh official said.