Many around the world are expressing disappointment with the death of Laszlo Csatary at the age of 98, not out of sadness, but because they wanted to see him survive long enough to be punished for the many war crimes he is believed to have perpetrated.

“He lived too long,” Holocaust survivor Ted Bolgar told CTV Montreal. “He owes me 70 years for my family.”

After the war, the Hungarian Csatary lived a comfortable life in Montreal and Toronto and worked as an art dealer at least until 1997, in spite of the fact that he had been sentenced to death in his absence in Czechoslovakia in 1948 for war crimes.

Csatary is believed to have sent nearly 16,000 Jews to concentration camps from Kosice, a collection point then in Hungary but now part of Slovakia.

Csatary died of pneumonia after being put under house arrest in Hungary last year. The charges had been put on hold for legal reasons.

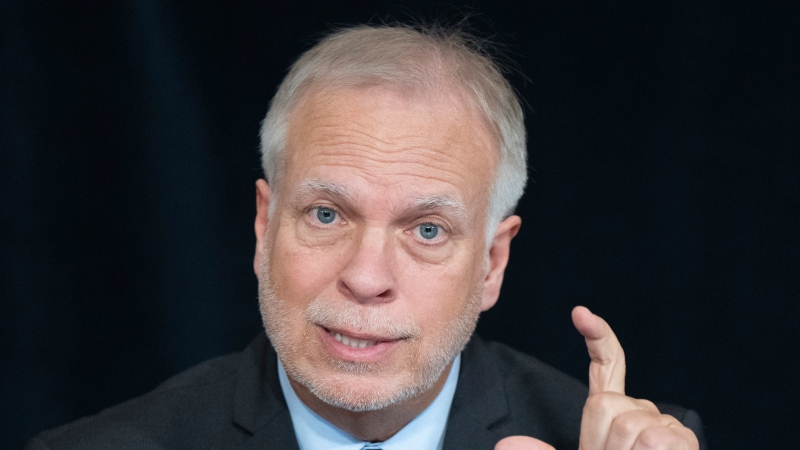

“The fact that this man about whom we're speaking now was able to live for close to 50 years without ever being touched by the authorities is a mark of shame for Canada,” said Rabbi Reuben Poupko of the Beth Israel Beth Aaron Congregation.

Laszlo Csatary was a former police officer who was stripped of his Canadian citizenship and indicted by Hungarian authorities for abusing Jews and contributing to their deportation to Nazi death camps.

Hungarian authorities claimed earlier this year that Csatary was the chief of an internment camp set up in a brick factory in 1944 for around 12,000 Jews in Kosice -- a Slovak city then part of Hungary.

They accused him of beating the Jews with his bare hands and a dog whip regularly and without reason.

He had also been charged with "actively participating" in the deportation of thousands of Jews to Auschwitz and other Nazi death camps.

According to the indictment filed by Hungarian prosecutors in June, Csatary rejected a request by one of the deportees to allow a ventilation hole to be cut into the wall of a railroad car on its way to a death camp and crammed with around 80 people.

"With his actions, the accused wilfully assisted in the illegal killings and torture carried out against the Jews deported from Kosice to the concentration camps in areas occupied by the Germans," the indictment said.

Csatary denied all those charges.

Holocaust survivor Edita Salamonova, whose family was killed in the Auschwitz death camp after their deportation from Kosice, said she remembered Csatary well.

"I can see him in front of me," Salamonova told The Associated Press in an interview in Kosice last year. "A tall, handsome man but with a heart of stone."

Salamonova remembered Csatary's presence at the brick factory, which has since been torn down, and would make sure to keep out of his sight when he was around.

"One had to hide. You never knew what could have happened anytime," said Salamonova, who was able to return home after enduring several Nazi camps.

Gusztav Zoltai, a Holocaust survivor and managing director of the Federation of Jewish Communities in Hungary, told the AP:

"How could I forgive? I lost 17 members of my family during the Holocaust, including my parents. I have no right to forgive! If I do, I'd violate their memories. But reconciliation is our duty."

Hungarian rabbi Zoltan Radnoti said in an interview that scarring from such atrocities never disappears, but "we have to focus on the prevention, teaching our children, grandchildren in a way that they would never think about racism again."

Csatary was initially convicted in absentia for similar war crimes in Czechoslovakia in 1948 and sentenced to death.

He arrived in Halifax the following year and became a Canadian citizen in 1955. He worked as an art dealer in Montreal.

In 1997, Csatary who went by the name Ladislaus Csizsik-Csatary, quietly left Canada as authorities prepared to serve him notice of a deportation hearing at his home in Toronto.

Federal cabinet had revoked his citizenship on the basis he had lied about his past when he came to Canada, telling authorities he was a Yugoslav national.

Last month, a Budapest court suspended the current case against Csatary because of double jeopardy, as the charges filed by Hungarian prosecutors were similar to those in his 1948 Czechoslovakia conviction. Hungarian prosecutors appealed the decision and a ruling was pending.

Slovakia recently changed the 1948 conviction to life in prison -- the death sentence is banned in the European Union -- and was considering an extradition request for Csatary.

Csatary's case and his whereabouts were revealed in 2012 by the Simon Wiesenthal Center, a Jewish organization active in hunting down Nazis who have yet to be brought to justice.

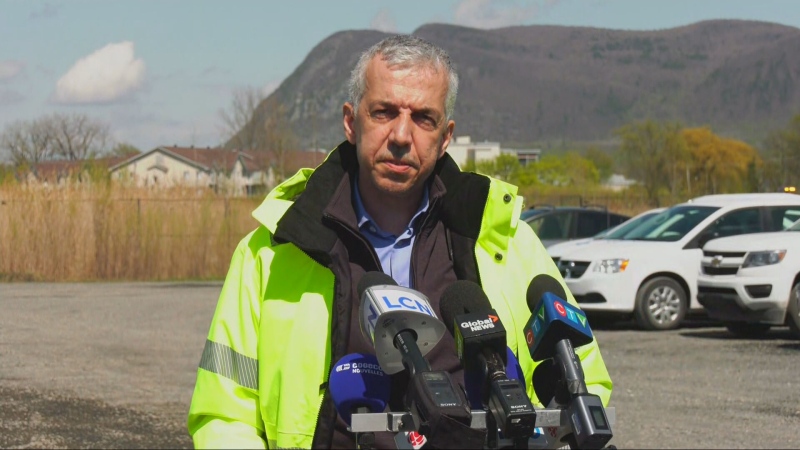

Efraim Zuroff, director of the Simon Wiesenthal Center's Jerusalem office, said they were "deeply disappointed" in Csatary's death ahead of his possible trial in Hungary, where he had lived since leaving Canada, and said the case cast doubts on Hungary's commitment to punishing war criminals.

"It is a shame that Csatary, a convicted ... and totally unrepentant Holocaust perpetrator who was finally indicted in his homeland for his crimes, ultimately eluded justice and punishment at the very last minute," Zuroff said in a statement.

Sandor Kepiro, another Hungarian suspect tried for war crimes after his whereabouts was disclosed by the Wiesenthal Center, died in September 2011, a few months after being acquitted due to insufficient evidence. His verdict also was being appealed when he died.

Csatary was born March 4, 1915, in the central Hungarian village of Many. Information about his family and funeral arrangements were not immediately available.

-With a file from The Associated Press