MONTREAL -- I’ve been meaning to sit down with my Great Uncle George to ask him about the war, for years.

The stories of his courage and valour and suffering exist in our family lore, but I wanted to hear his account first hand - to make a record of it - so my kids could someday understand the role their family played in the fight for freedom.

Men of his generation are usually hesitant to speak about their time overseas, so perhaps for a long time, I was nervous to even ask. But this past week, likely due to some combination of the pandemic and the fact that George turned 95 years old this year, I suddenly felt a sense of urgency.

"I have some pleasant memories, and some that aren't too pleasant,” he told me over a video call.

Flying Officer George Arvanetes was just 18 years old when he volunteered to become a rear gunner with Montreal’s 425 Squadron, one of the most dangerous jobs in the Air Force.

"They needed gunners,” he said. “That's why I was accepted.”

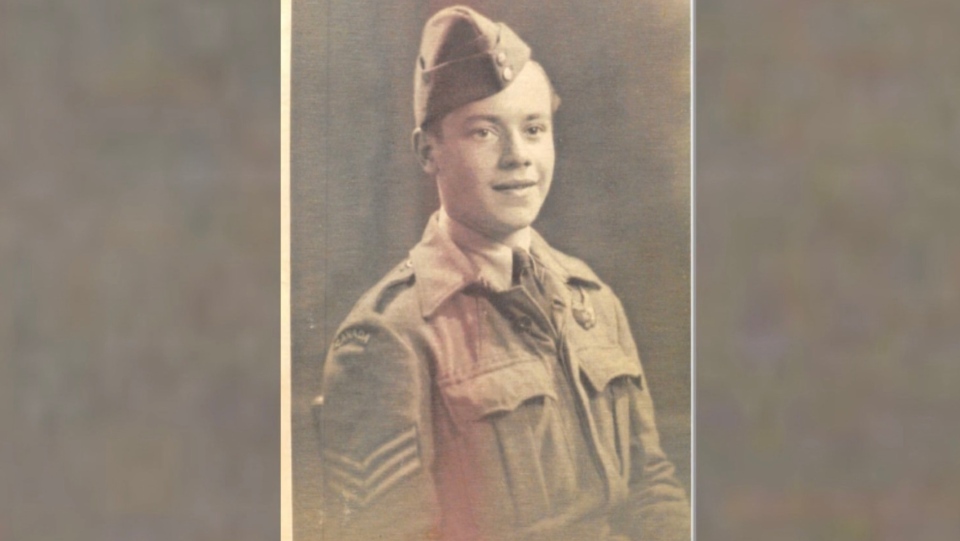

Pilot Officer George Arvanetes at age 18, in 1943.

He originally tried to enlist in the navy. That’s where all his friends were going. But he was rejected because he was too short.

“I wasn't too small to be a rear gunner," he laughed. “I ended up in the heat of the action. Moreso than the rest of them.”

The rear gunner’s job was to protect the back of the aircraft from enemy fire. Arvanetes did the majority of his flights on a Halifax bomber. His office, the rear turret, was nothing more than a seat and four machine gun barrels, perched at the very tip of the tail, shielded only by a five-foot by three-foot plastic dome.

“It was cold as hell,” he said. “I wore two suits.”

At times it was thrilling, he said. At other times it could be terrifying. He was often the target of enemy fighters. Without a rear gunner, the bomber would be a sitting duck.

"When you start off it's exciting and whatnot, and you look forward to it,” he said. “But, after a while, it's not exciting anymore."

I asked him if there was a moment when he realized the danger he had put himself in.

"Oh yeah, as a matter of fact, around the thirteenth or fourteenth flight, you don't think you're going to be able to make it."

Not many did.

Less than a third of Canadian rear gunners in World War II ever completed their full 32-flight tour, according to the Bomber Command Museum of Canada. The average life expectancy was just 10 or 15 flights and more than half were killed in action.

"You just seem to take it in stride,” he said of the many friends he lost. “You wonder, well, where's Harrison and his crew? Someone would perk up and say 'He bought the farm' and that was it.”

Whether it was luck or determination, my Uncle George made it through the war.

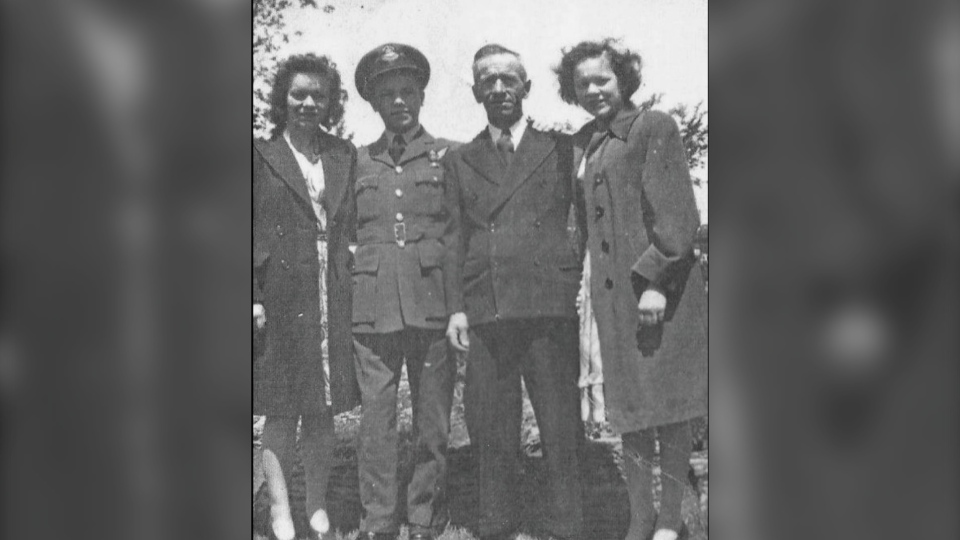

George centre left, after the war, with his father Evangelos (centre-right) and sisters Elaine (left) and Violet (right).

"This is very important to me,” he said, pointing to a small wing-shaped pin. It was framed along with other medals Arvanetes had earned and old photos of him as a young man in uniform.

“It indicates that I completed a tour of 32 flights."

Directly above them hangs a Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC), awarded to Arvanetes by the Governor General for courage and devotion to duty.

In October 1944, his Halifax bomber came under enemy fire.

“Arvanetes manipulated his guns with great skill and drove the enemy off,” reads a notice in the London Gazette, announcing he had been awarded the DFC.

George Arvanetes in front of the rear turret of a WWII era bomber, at an Air Force reunion at CFB Bagotville, 1992.

A handwritten copy of the notice still hangs beside the medal.

“That’s worth keeping,” Arvanetes said, pausing for a moment. “They’re not fond memories, but memories.”

The horrors of what Arvanetes witnessed are etched in the lines of his now 95-year-old face. It’s been a lifetime since he returned home, at just 20 years old, but the experience forever changed him.

"It has never left,” he said, after a long pause. “You often still wonder why and whatnot. It never leaves you."

“You just learn to cope with it,” he said. “Not readily, or happily. But, when the bell rings, you gotta show up."

George Arvanetes today, at age 95.

Arvanetes told me the determination it took to make through the war wasn't something he was born with or even learned. He doesn’t think it was necessarily a generational thing either.

The circumstances, he said, simply took over.

And young men and women from around the world, barely out of high school, did what needed to be done. Then, paid for it for the rest of their lives.

My Uncle George doesn't see himself as having any wisdom to pass down. But, stories like his, of the men and women who serve, are worth telling.

Lest we forget the true cost of war.