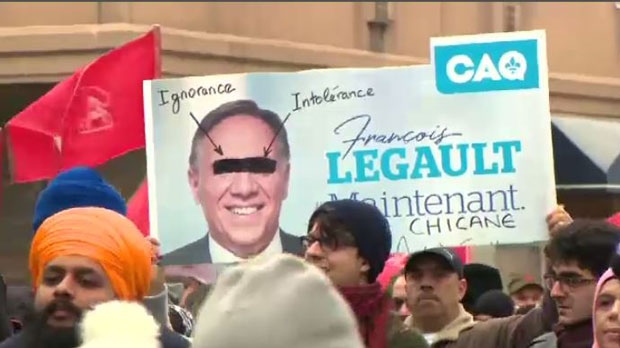

MONTREAL -- Immigrants and visible minorities are noticing how some of the most significant pieces of legislation introduced by the Coalition Avenir Quebec government since it took power last October have something in common: the bills disproportionately affect them.

Quebec's Bill 21, which bans some public sector employees including teachers and police officers from wearing religious symbols, has drawn widespread criticism since Minister of Immigration, Diversity and Inclusiveness Simon Jolin-Barrette tabled it last month.

The bill targets all religious symbols. But Haniyfa Scott, a teacher at Montreal's Carlyle Elementary School, says it is Muslim women who wear the hijab -- as she does -- who will feel it the most. "I'd like for the government to live a week in the shoes of all the people they are targeting," she said in an interview Monday.

While the secularism bill has grabbed a lot of attention, two other major pieces of legislation addressing immigration levels and the province's taxi industry have had outsized effects on the province's minority communities.

Transport Minister Francois Bonnardel's Bill 17, tabled last month, overhauls a taxi industry that is heavily composed of immigrants. Joseph Naufal, the director of a taxi company in east-end Montreal who also works for the industry association, said "easily 90 per cent" of Montreal taxi drivers are first- or second-generation immigrants.

The drivers say the Quebec bill, which abolishes a permit system, will drive many of them into bankruptcy.

Drivers who blocked downtown Montreal streets last week in protest said Bill 17 mainly affects immigrants who took out loans to finance their permits. If the bill is adopted and the permits lose their value, drivers say the compensation offered by the province will not cover their deep debts.

Abdelahk Bentarcheh, 36, who immigrated four years ago from Morocco, said that as a taxi driver, he feels targeted by Bill 17, and as a Muslim he feels targeted by Bill 21. "The government is trying to radicalize the public's opinion on Islam," Bentarcheh said of the secularism bill.

Another bill affecting the immigrant community was tabled in February by Jolin-Barrette. Bill 9 creates a legal framework granting the government the authority to be more selective over who receives permanent residency in Quebec.

Shortly after introducing the bill, Jolin-Barrette signalled the government would throw out a backlog of 18,000 immigration applications from people around the world, including roughly 3,700 applications from people already residing in the province. The government told them to reapply under a new system.

Jolin-Barrette's plan was stopped on Feb. 25, when a Superior Court judge granted an injunction and ordered the government to resume processing the applications.

Doug Mitchell, one of the lawyers who took the government to court, said Jolin-Barrette's decision to cancel 18,000 applications "had no justification." He added that when one looks at Bill 9, 17 and 21 together, it seems as though immigrants are being disproportionately hit.

"I suppose that's the logical conclusion," he said in an interview Monday. "It's a little disturbing, when you think of it."

Ewan Sauves, spokesman for Quebec Premier Francois Legault, said it's "totally false to claim bills 9, 17 and 21 ... target one community or one religion in particular." The Coalition Avenir Quebec, he said in an email, has tabled 18 bills since coming to power that touch many different parts of the economy and Quebec society.

"Whether it's about immigration, transportation, or state secularism, the same rules are in place for everyone," he added. "During the election campaign, we were transparent regarding our intentions. We are doing what we said we were going to do. Quebecers, in large numbers, endorsed our ideas last October."

Scott is planning on retiring soon, so she does not expect to be directly affected by Bill 21. The legislation allows teachers already in the school system to continue wearing religious symbols, as long as they don't seek promotion or change school boards.

She said the government's actions since October make members of some communities feel like second-class citizens.

"I think that Quebec has always been known as being a unique society and (the government) is proving that fact, but not in a good way," Scott said. "Why isn't the rest of Canada treating people like this?"