OTTAWA -- A constitutional battle will be engaged today over whether the government is free to change the rules for the top court in the land.

It didn't start out that way, but last fall's unremarkable appointment of Federal Court of Appeal Judge Marc Nadon to the Supreme Court of Canada has opened up a legal can of worms.

Seven interveners are taking part, including the federal and Quebec governments, an association of provincial court judges and a number of constitutional experts.

The repercussions could extend far beyond the employment future of Nadon, Prime Minister Stephen Harper's sixth appointment to the nine-member Supreme Court bench.

Among the scenarios presented in court factums are a Quebec separatist movement reinvigorated by Ottawa's court manoeuvres and a Supreme Court stacked with partisan appointees by the government of the day.

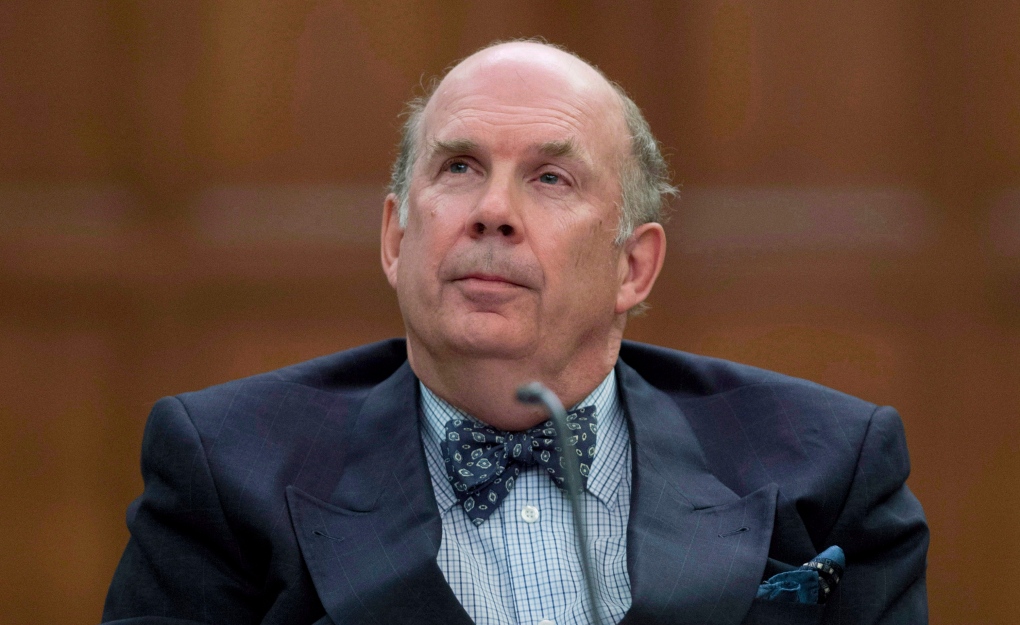

"Canadians who care about their country should" care about the case, constitutional expert Peter Russell said in an interview.

"The Supreme Court is called upon all the time to make extremely important decisions about the Constitution of Canada that limits and defines the powers of our governments."

Not since the Supreme Court was created by an act of Parliament in 1875 has there ever been a hearing quite like today's.

Nadon, 64 and semi-retired before he was plucked from obscurity last September, faces a constitutional challenge because he may not meet the criteria to sit as one of the three Quebec-based judges that are required on the nine-member bench.

Part of the case involves a parsing of the French and English language of the appointments section of the act, which differ slightly.

The government "absolutely knew this was an issue," said Adam Dodek, a constitutional law professor at the University of Ottawa.

Justice Minister Peter MacKay sought a legal opinion from retired Supreme Court judge Ian Binnie to buttress Nadon's appointment even before it was announced.

The government subsequently used an omnibus budget bill to redraft the Supreme Court Act language to "clarify" that Nadon was in fact eligible.

But by then a constitutional lawyer and the Quebec attorney general had signalled their intention to challenge the appointment's legality.

"The court has been put in this awkward position by the government," said Dodek.

The court had to issue a public notice stating that Nadon, already sworn in as Harper's sixth Supreme Court appointee, had been told stay away from case files and off the court premises until the legal questions are resolved.

What may be at stake is whether Parliament can rewrite the rules for appointing Supreme Court justices as it sees fit.

That's the angle taken by the Constitutional Rights Centre and lawyer Rocco Galati, who together launched the initial challenge.

The rights centre argues in a factum, for instance, that the government could conceivably redraft the rules so that "only card-carrying Conservatives" are eligible for appointment.

Galati and the centre believe the 1982 patriation of the Constitution "constitutionalized" the Supreme Court's appointment rules and only a constitutional amendment can alter them.

The government argues that a narrow interpretation of the Supreme Court Act could effectively bar any Federal Court judge from being appointed to the top bench, effectively making an already small pool of qualified jurists even smaller.

The Canadian Association of Provincial Court Judges makes a similar case, and extends the diversity argument to the lower courts as well.

The hearing is expected to wrap up by mid-afternoon, but it could take weeks or months before the court issues its response to the government reference on what rules apply to Quebec appointments to the bench.