One year after the adoption of Quebec's child labour law, what are the results?

Quebec Labor Minister Jean Boulet receives congratulations from his colleague Jean-Francois Roberge at the National Assembly. Photo taken February 1, 2024. LA PRESSE CANADIENNE/Jacques Boissinot

Quebec Labor Minister Jean Boulet receives congratulations from his colleague Jean-Francois Roberge at the National Assembly. Photo taken February 1, 2024. LA PRESSE CANADIENNE/Jacques Boissinot

It will soon be a year since the Quebec legislature adopted the Act respecting the regulation of child labour, sponsored by Minister Jean Boulet. Has it achieved its objectives?

"Yes," says Boulet in an interview with The Canadian Press. He notes a marked reduction in work-related accidents among young people.

The law sets the minimum working age in Quebec at 14, with some exceptions, and prohibits 14- to 16-year-olds from working more than 17 hours a week during the school year, except for vacations.

The minister set two objectives: to ensure the health and safety of children and to promote school retention and educational success.

The law came into force in two stages: employers who employed a youth under 14 had 30 days from June 1, 2023, to send them a notice of termination.

Three months later, on Sept. 1, young people aged between 14 and 16 saw their working hours limited to 17 per week (including weekends) during the school year, excluding vacations.

From Monday to Friday, this means a maximum of 10 hours.

Armed with a preliminary assessment, Minister Boulet asserts that the law has had a positive effect on young people. By 2023, occupational injuries among minors had fallen by 19 per cent compared with 2022.

For those under 14, this represents a drop of 33.3 per cent, and for those 16 and under, a drop of 17 per cent.

Looking more closely at the months from June to December 2023, the months following the law's passage, the figures are even more telling: under-14s saw a 41 per cent drop in work-related accidents compared with the same period in 2022, and 16 and under, a 17 per cent drop.

"I'm very satisfied," said Boulet, smiling. "Remember what motivated us. From 2017 to 2022, there had been a 640 per cent increase in occupational injuries among under-14s, 80 per cent among 16s and under."

"As a society, we can be proud of our contribution to reducing the number of childhood injuries," he added. "We've put the brakes on that upward slope ... We need to keep going in the same direction."

As for student retention, the minister says he is waiting for data from the Réseau québécois pour la réussite éducative, which will be updated this fall, before drawing any conclusions.

582 compliance inspections

To enforce the law, the Commission des normes, de l'équité, de la santé et de la sécurité au travail (CNESST) carried out 582 compliance inspections between June and December 2023.

Ten infractions were found, four of which concerned the prohibition of work for a child under the age of 14.

Three related to the requirement to obtain and retain the written consent of the holder of parental authority to work, exceptionally, with a child under 14.

One offence related to failure to comply with the prohibition on employing a child between 11 p.m. and 6 a.m.; another concerned the obligation to register the date of birth of a worker under 18.

A final offence involved a child working more than 17 hours a week, or 10 hours from Monday to Friday.

The law provides for hefty fines for offending employers: $1,200 for a first offence and $12,000 for a repeat offence. Of the 10 infractions, only one fine was issued, and the employer decided to contest it.

The minister makes no secret of the fact that there was "resistance," especially in the restaurant and retail sectors, which were calling for greater flexibility on the part of the government, in particular to allow young people under the age of 14 to obtain piecework exemptions.

However, with the Comité consultatif du travail et de la main-d'œuvre, a grouping of union and employer associations, "we had reached a consensus ... and this gives ... support to resist", he says.

To parents who disagree with the law because they would prefer their 12-13-year-old child to work instead of sitting in front of a screen, the minister said that children should be encouraged to develop in other ways, through play

"There are summer camps, reading, playing with friends, outdoor activities. You can't say, 'If my child doesn't work, he'll just be on the screen.' You have to make sure your child is well looked after, and that means a multitude of educational activities. There are lots of them during the summer," Boulet said.

"It's also the parents' responsibility to make sure that their children do their homework."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published in French on April 27, 2024.

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

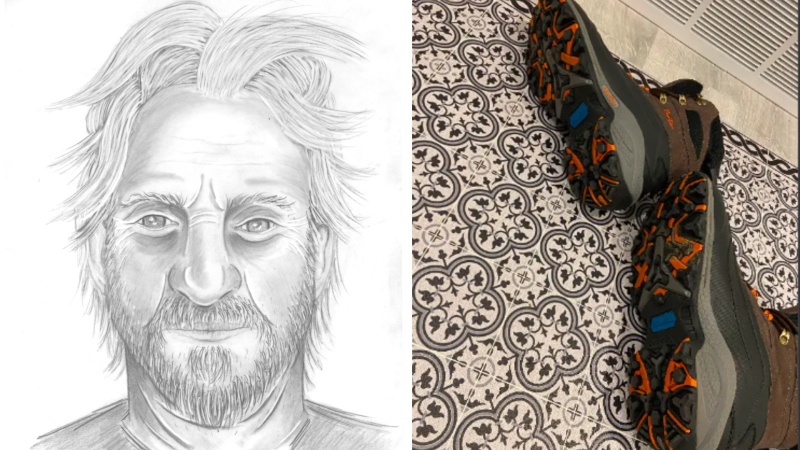

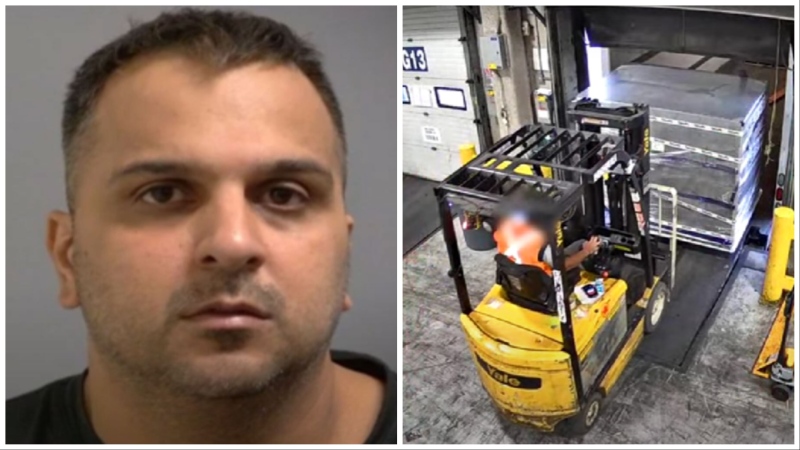

BREAKING Another suspect arrested in Toronto Pearson airport gold heist: police

Another suspect is in custody in connection with the gold heist at Toronto Pearson International Airport last year, police say.

BREAKING Justin and Hailey Bieber are expecting their first child together

Hailey and Justin Bieber are going to be parents. The couple announced the news on Thursday on Instagram, both sharing a video that showcases Hailey Bieber's growing belly.

From outer space? Sask. farmers baffled after discovering strange wreckage in field

A family of fifth generation farmers from Ituna, Sask. are trying to find answers after discovering several strange objects lying on their land.

Poilievre-led government 'would never' use notwithstanding clause on abortion, his office says

A Conservative government led by Pierre Poilievre would not legislate on, nor use the notwithstanding clause, on abortion, his office says, as anti-abortion protesters gather on Parliament Hill.

Ontario family receives massive hospital bill as part of LTC law, refuses to pay

A southwestern Ontario woman has received an $8,400 bill from a hospital in Windsor, Ont., after she refused to put her mother in a nursing home she hated -- and she says she has no intention of paying it.

Here are the ultraprocessed foods you most need to avoid, according to a 30-year study

Studies have shown that ultraprocessed foods can have a detrimental impact on health. But 30 years of research show they don’t all have the same impact.

Miss Teen USA steps down just days after Miss USA's resignation

Miss Teen USA resigned Wednesday, sending further shock waves through the pageant community just days after Miss USA said she would relinquish her crown.

Why these immigrants to Canada say they're thinking about leaving, or have already moved on

For some immigrants, their dreams of permanently settling in Canada have taken an unexpected twist.

Cyclist strikes child crossing the street to catch school bus in Montreal

A video circulating on social media of a young girl being hit by a bike has some calling for better safety and more caution when designing bike lanes in the city. The video shows a four-year-old girl crossing Jeanne-Mance Street in Montreal's Plateau neighbourhood to get on a school bus stopped on the opposite side of the street