More people will be diagnosed with neurocognitive disorder in Quebec by 2050

The number of people living with neurocognitive disorders could jump by 145 per cent in Quebec by 2050, warns a new report from the Alzheimer Society of Canada, whose findings were shared with The Canadian Press ahead of their unveiling on Monday.

More than 360,000 Quebecers may develop a neurocognitive disorder by 2050, according to the report.

Across Canada, that number could increase to 187 in the same timeframe -- that's more than 1.7 million people.

"We now know what we're up against," says Sylvie Grenier, general manager of the Fédération québécoise des Sociétés Alzheimer. "We've been announcing it for several years, but now we have the figures. Now we have to work to ensure that these people are supported, that their quality of life is maintained."

The number of people of African descent living with neurocognitive disorders in Quebec is expected to rise from 1,460 to 11,490 by 2050, a jump of 687 per cent.

The anticipated increase is expected to be 683 per cent for people of Asian origin and 271 per cent for Indigenous people.

The document states: "Given the evolution of immigration trends, the ethnic profile of Canada's seniors is changing. This changing population profile is directly reflected in the ethnic origins of those likely to develop a neurocognitive disorder over the next 30 years."

In addition, women are twice as likely as men to suffer from neurocognitive disorders.

By 2020, around two-thirds of people living with a neurocognitive disorder in Canada were women.

If current trends continue, more than 100,000 women will be diagnosed with a neurocognitive disorder every year in Canada by 2028.

Just over 91,500 people living with neurocognitive disorders in Quebec in 2020 were women, and that could jump to more than 225,000 by 2050, according to the study "The Many Facets of Neurocognitive Disorders in Canada."

"Now that we have this in front of us, we have to act," Grenier said.

A question of origins

While the report highlights the challenges facing Quebec and Canada in general, it also sheds light on the situation within different sub-populations, be they people of Indigenous, African or Asian descent.

As is the case for the population as a whole, the aging Indigenous population is accompanied by an increased risk of neurocognitive disorders, the document states.

The study also points out that "colonization is a root cause associated with the risk of neurocognitive disorders and other health problems in Indigenous populations."

The legacy of colonization, it points out, includes "socioeconomic disadvantage that limits healthy choices (diet, physical activity, taking medication, etc.), increases stress levels and decreases the ability to take care of oneself and change to adopt healthy behaviour."

Socioeconomic context, the study's authors continue, can have a significant impact on modifiable risk factors for neurocognitive disorders, such as diabetes, low education, head injury, cardiovascular disease, alcohol consumption, childhood trauma, mid-life hypertension, obesity, sedentary lifestyle and smoking.

Income, employment, food security, housing and social exclusion are also important factors to consider.

"As a result of the many impacts of colonialism, Canada's Indigenous populations are at increased risk of neurocognitive disorders associated with the social determinants of health -- the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age -- over which individuals have little control," reads the document.

This is in addition to the fact that Indigenous people have often been at the mercy of discriminatory shortcomings within the province's health care system.

The document warns that "Canada's Indigenous people face a range of barriers to accessing good care and, by extension, good care for neurocognitive disorders."

The study pinpoints poverty, cultural and linguistic differences, racism and lack of cultural safety in health care, mistrust of health care providers, stigma associated with neurocognitive disorders and the distance separating communities from health care centres as factors that prevent Indigenous populations from accessing the care they need.

"Racism experienced over many years is a form of psychosocial stress that causes structural changes in brain physiology, accelerating aging and memory decline," the study points out.

It notes the number of Indigenous people living with a neurocognitive disorder will increase the most in Ontario by 2050; Quebec comes in second.

Building bridges

Nevertheless, little data is available on the impact of neurocognitive disorders on Indigenous populations.

A few studies carried out over the years, most notably in Alberta, have shown higher rates and a more rapid increase of neurocognitive disorders among Indigenous populations.

Grenier admits that links need to be forged.

"We're not involved in the (Indigenous) communities. They don't come to us but we know they are affected," she said. "I've been working for some time now to create links with these communities, to ensure that we work with them. We want to do it with them."

The goal, she says, is to ensure that "no one goes it alone," adding there is a need to reach as many people as possible, "to be able to inform, to equip communities to take care of their seniors and also ensure that we maintain their quality of life so there is less impact."

"We're going to make sure that we work with the stakeholders in their communities to ensure that they are in a position to support their people," says Grenier. "We now know that healthy lifestyle habits, such as physical activity, diet, not smoking and so on, can delay the onset of the first symptoms by up to ten years. It's important that the entire population, Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike, has access to the resources and information they need."

Genier adds that 40 years ago, "a cancer diagnosis was a 'foregone conclusion," and the chances of recovery were slim.

Things are much the same when it comes to neurocognitive disorders, but that doesn't mean patients are helpless.

"It doesn't help if you don't go for a consultation because you'd rather 'not know,'" she said. "The sooner we have a diagnosis, the sooner we can intervene and work with people, accompany them to ensure that their quality of life is maintained. Life doesn't end with a diagnosis. We still have power over our lives at that point."

-- The Flagship Study is a microsimulation study conducted by the Alzheimer Society of Canada to better understand neurocognitive disorders in the Canadian population over the next 30 years.

The model used publicly available data from Statistics Canada to create "agents" that statistically represent people living in Canada.

-- This report by The Canadian Press was first published in French on Jan. 22, 2024.

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

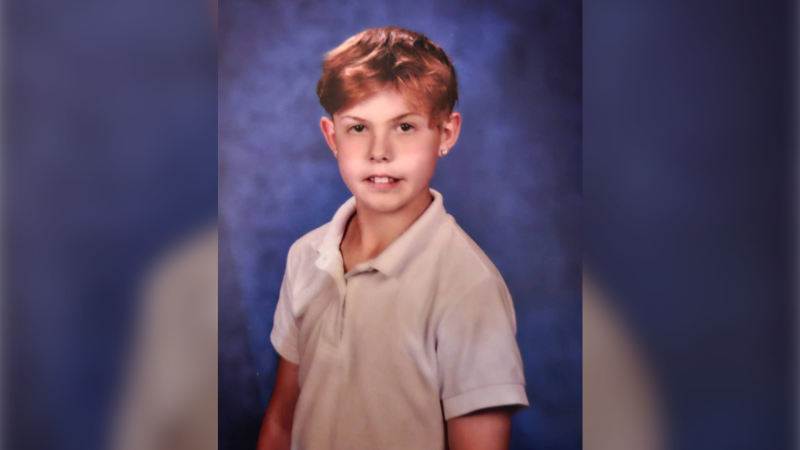

'A beautiful soul': Funeral held for baby boy killed in wrong-way crash on Highway 401

A funeral was held on Wednesday for a three-month-old boy who died after being involved in a wrong-way crash on Highway 401 in Whitby last week.

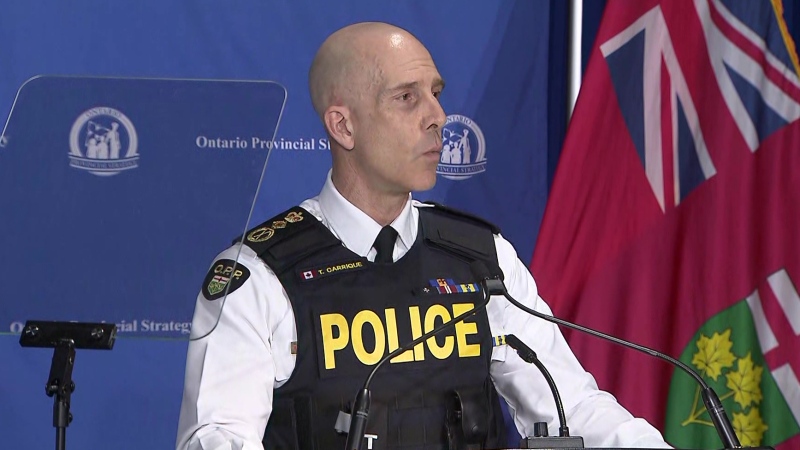

'Sophisticated' cyberattacks detected on B.C. government networks, premier says

There has been a "sophisticated" cybersecurity breach detected on B.C. government networks, Premier David Eby confirmed Wednesday evening.

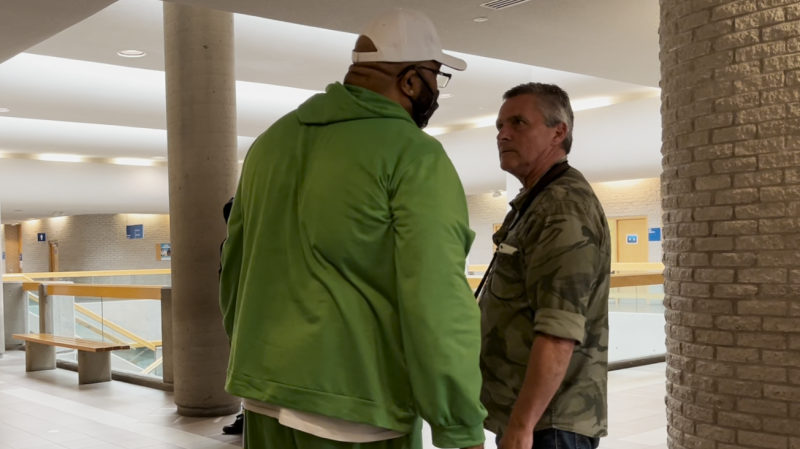

Police handcuff man trying to enter Drake's Toronto mansion

Toronto police say a man was taken into custody outside Drake's Bridle Path mansion Wednesday afternoon after he tried to gain access to the residence.

Biden says he will stop sending bombs and artillery shells to Israel if they launch major invasion of Rafah

U.S. President Joe Biden said for the first time Wednesday he would halt shipments of American weapons to Israel, which he acknowledged have been used to kill civilians in Gaza, if Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu orders a major invasion of the city of Rafah.

Canucks claw out 5-4 comeback win over Oilers in Game 1

Dakota Joshua had a goal and two assists and the Vancouver Canucks scored three third-period goals to claw out a 5-4 comeback victory over the Edmonton Oilers in Game 1 of their second-round playoff series Wednesday.

Nijjar murder suspect says he had Canadian study permit in immigration firm's video

One of the Indian nationals accused of murdering British Columbia Sikh activist Hardeep Singh Nijjar says in a social media video that he received a Canadian study permit with the help of an Indian immigration consultancy.

Pfizer agrees to settle more than 10K lawsuits over Zantac cancer risk: Bloomberg News

Pfizer has agreed to settle more than 10,000 lawsuits about cancer risks related to the now discontinued heartburn drug Zantac, Bloomberg News reported on Wednesday, citing people familiar with the deal.

Quebec premier defends new museum on Quebecois nation after Indigenous criticism

Quebec Premier Francois Legault is defending his comments about a new history museum after he was accused by a prominent First Nations group of trying to erase their history.

U.S. presidential candidate RFK Jr. had a brain worm, has recovered, campaign says

Independent U.S. presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr. had a parasite in his brain more than a decade ago, but has fully recovered, his campaign said, after the New York Times reported about the ailment.