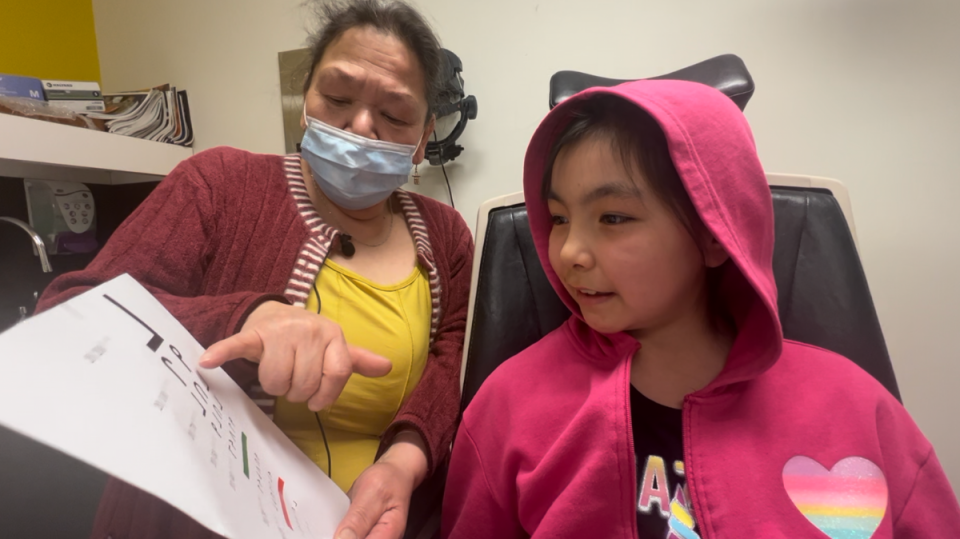

Pavvi Etok and her grandmother Annie Hubloo Etok came from Kangiqsualujjuaq, Que. to Montreal for an eye exam at the McGill University Health Centre's eye centre.

Unlike in years past, however, the young girl read her own language when reading down the visual acuity chart.

"Some people don't speak well in English, especially elders," said Hubloo Etok. "For kids, it's going to be helping."

Rather than starting with "E" and continuing down the chart of Latin characters, Pavvi starts with "mu," the ᒧ character.

"We developed the first known visual acuity chart in Canadian Aboriginal syllabics," said McGill University medical graduate Shaan Bhambra.

The chart will help the large majority of Inuit people who speak and read Inuktitut as their first language.

"The visual acuity is the first thing we do when a patient walks into a clinic," said ophthalmologist Dr. Christian El-Hadad. "If the patient's unable to accomplish that task because of a language barrier, then we cannot build the trust that we'd like to build with a patient."

The chart uses seven letters that are also used in Cree and Ojibwe languages. It has been distributed in 14 communities in Quebec's north and is being used in Montreal for the city's Inuit population.

"So we can cover 85 per cent of the 260,000 Indigenous Canadians who can read and speak an Indigenous language," said Bhambra.

El-Hadad travels as far as 1,800 kilometres north to Inuit communities and treats patients in very remote regions, and sees firsthand the number of barriers to health-care there are, such as distance, weather, technology and access to medical equipment.

Kangiqsualujjuaq, for example, is over 1,500 kilometres from Montreal and is only accessible by a series of flights.

One barrier the MUHC team is hoping to remove is language.

Many Inuit children are taught Inuktituk first and learn English or French much later in school.

"So it's difficult to have them test the visual acuity," said El-Hadad.

The chart helps the patient feel more comfortable, addresses part of the language barrier and allows doctors to test more patients, El-Hadad said.

"They are very excited and very happy to use their own alphabet, to feel more comfortable in a medical setting as well," said Bhambra. "It's been really inspiring to have that sort of impact on patients in ophthalmology, and we hope to inspire this in other fields of medicine as well."

The doctors found that most of those who read Inuktitut and English scored equal or better using the Inuktitut chart compared to the Latin one.

"For these patients who use Inuktituk in their daily lives, using a visual acuity chart in English or French may be uncomfortable for them," said Bhambra. "We wanted to provide patient-centric care in a way that would address the cultural uniqueness of the patients in Nunavik and the Inuit patients in general."

"Trust is key in health-care, so if you're able to establish that level of trust from the get-go, from the first encounter, from the first step in the encounter, that is super, super important because then we can discuss more important stuff and not worry about the language barrier," said El-Hadad.