MONTREAL -- For First Nations peoples in Quebec, the provincial government’s decision to create a task force to combat racism seems impractical when there are already several useful tools available.

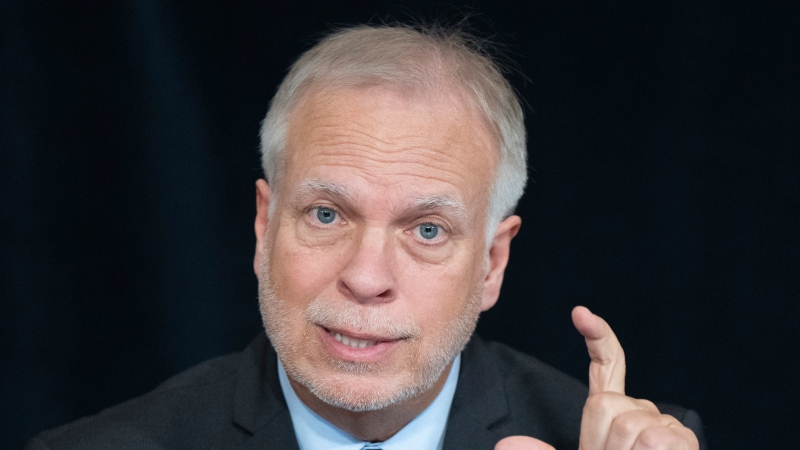

Following the release of a report on the prevalence of systemic racism and discrimination in Montreal, Premier François Legault announced on Monday that an “action group” composed of ministers and deputies will put together a list of recommendations as early as this fall, particularly on matters of employment, education and housing for minority communities.

When asked if any Indigenous people will be working on the file, Legault said there won't be because there aren't any in his government.

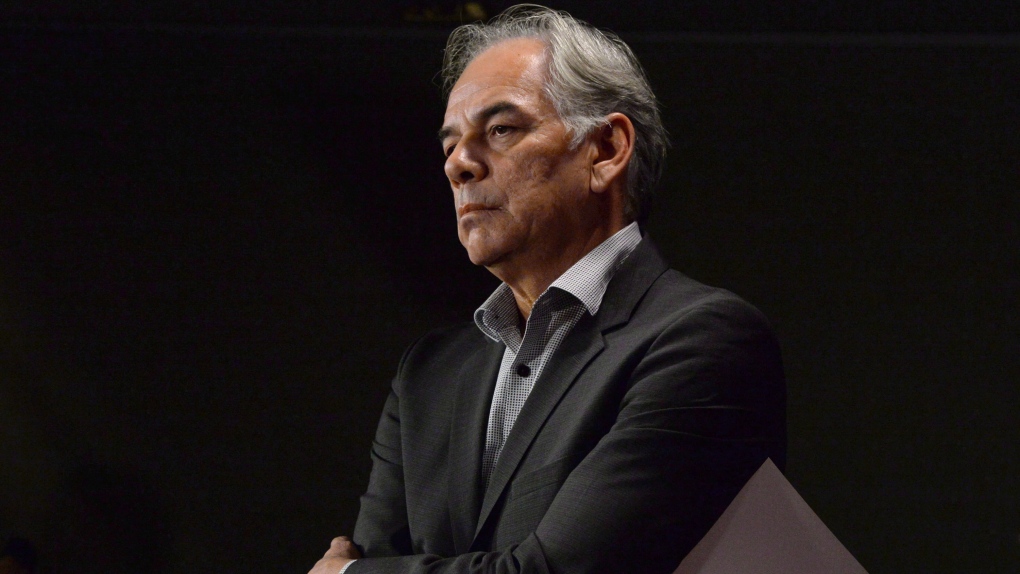

“For us, the plan is there,” Assembly of First Nations of Quebec and Labrador (AFNQL) Chief Ghislain Picard told CTV News on Tuesday. “So why do we need another six months before we put something together?”

The Viens Commission – a report on the relations between Indigenous peoples and public services in Quebec that was released last year – already provides dozens of recommendations to the province on how it can better serve First Nations communities, Picard said. So does the report on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

“Why do we need to again consult our peoples? I think peoples on the ground, those who have to live through racism, want action now,” Picard said.

In October of 2019, the government formally apologized when the Viens Commission was released but “has failed to take action on the recommendations,” Picard said. “The solutions are laid out… Seventy plus recommendations provided by the report.”

The topic of systemic racism has gained traction in Quebec following the murder of George Floyd, a Black man who died in police custody in Minneapolis after a white officer kneeled on his neck for nearly nine minutes.

Just a few weeks later, footage surfaced of Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation Chief Allan Adam being violently arrested by the RCMP on his way out of a casino in Alberta.

Both incidents involved law enforcement using excessive force on members of minority communities, and neither of them were isolated occurrences.

Still, despite similar situations occurring in Quebec, Legault refuses to characterize racism in the province as “systemic,” and claims arguments over a word halt Quebec’s ability to move forward, though he does admit racism is a problem.

“I think there’s a consensus – a large consensus, if not unanimity – on two things,” he said during his press briefing on Monday. “One, the large majority of Quebecers aren’t racist, and two, there is racism in Quebec.”

But in Montreal in particular, a report in the fall of 2019 proved the city’s police force has racial bias in terms of who it stops for street checks – with Black and Indigenous Montrealers being over four times more likely to be stopped. Members of minority communities have been shot and killed by Montreal police in the past, as well.

Following a petition that received over 22,000 signatures in 2018, the city of Montreal mandated an independent body to conduct a public consultation into systemic racism and discrimination on its territory. The resulting report, released on Monday, says Montreal has failed to acknowledge systemic racism and discrimination in the city and in so doing, has also failed to recognize the role it plays in the perpetuation of inequality.

Montreal Mayor Valérie Plante held a press conference to address the report, during which she admitted the city’s shortcomings.

“Starting today, at city council, I will propose a statement to recognize the systemic nature of racism and discrimination,” she said. “I’m committed to implementing systemic solutions to these systemic problems.”

Picard pointed out the contradiction of one official admitting the existence of systemic racism when just a few hours later, another refused to do the same.

“Why would you want to be the only one putting yourself in a corner when everyone else agrees that there’s systemic racism?” Picard said. “Here you have the biggest metropolis in the province of Quebec stating that fact and you have the premier of that same province saying something completely different.”

Because the Quebec government made a point of apologizing for its shortcomings when the Viens Commission was released but then failed to deliver results, Picard said communities are skeptical.

“On one hand, you deny that systemic racism exists, and on the other hand you open your arms to a report that really states that the system has failed Indigenous peoples,” he said. “The Viens Commission report was about the failure of the system in addressing Indigenous issues and not really delivering in terms of how the nation to nation relationship, if you will, translated to the services provided by the Quebec government to our peoples.”

As protests over Floyd’s death, police brutality and systemic discrimination continue to take place around the world, Picard said this is one of those rare times when the public is paying attention.

The government delaying its action on fighting systemic racism to the fall could mean that the fire will die out before then.

“Sometimes, when it concerns issues – Indigenous peoples’ issues, and minority issues – people quickly forget, and I think the government is really counting on that to happen in this case,” he said. “…This kind of international mobilization will, at some point, lose its effectiveness.”

Picard said First Nations communities are paying attention, taking steps and reacting accordingly.

“For me, the city as well as the province have their hands full and the expectation from our peoples is for someone to deliver, and not only have that feel good moment before the cameras,” he said. “What happens next?”