MONTREAL -- This week marks the 50th anniversary of the October Crisis: a time when a militant independence movement led by the Front de Libération du Quebec terrorized Quebec society, and the War Measures Act was put in place - for the first time in Canada during peacetime.

The Crisis came in the wake of years of bombings and robberies by the FLQ, done to draw attention to the inequalities and repression experienced by the province’s French-speaking majority at the hands of the English-speaking minority.

By 1970, six people had been killed, and dozens more were injured during the FLQ’s campaign of violence to create a Quebec State.

The October Crisis marked the beginning of an escalation: the kidnapping of British diplomat James Cross, and five days later, the kidnapping and eventual murder of Quebec cabinet minister Pierre Laporte.

“The events of the October Crisis were so dramatic, so appalling, that if they could do this, what's next?” said Rick Leckner, a former radio reporter.

In 1966, Leckner joined English radio station CKGM. The station was a target of the FLQ , which threw a Molotov cocktail at the building housing the station.

Cross and Laporte’s kidnapping outlined a crisis that shocked Canada’s foundation as a nation of law.

With the country on edge in the face of the violence in Quebec, for only the third time ever, then-prime minister Pierre Trudeau imposed the War Measures Act.

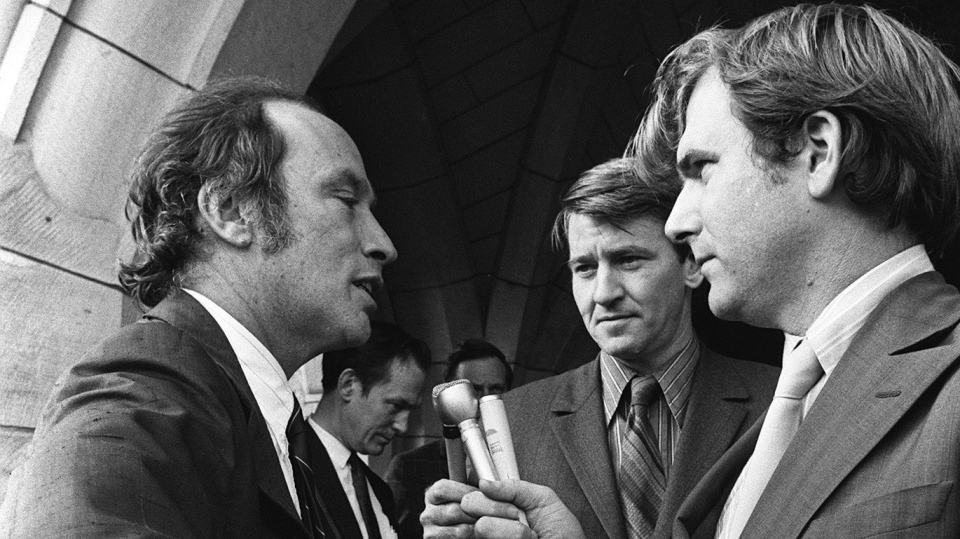

photo: Reporters Tim Ralfe (right) and Peter Reilly (centre) question Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau (left) on the steps of Parliament Hill about the FLQ crisis and the invocation of the War Measures Act, Oct. 13, 1970. The question by Ralfe elicited the famous quote by Trudeau, "Just watch me". (CP PHOTO/Peter Bregg)

It was a move Marc Lalonde, a former advisor to Trudeau, said was justified.

“We had frankly no information of significance about the reality or the size of that group. The reality, we saw it, people were kidnapped, but their size we didn't have,” said Lalonde.

The move allowed police officers to arrest and detain people without probable cause or a warrant. The controversial move, while praised by some, was condemned by others.

photo: A car load of suspected separatists, shaking their fists are brought into a police station Oct. 16, 1970 as soldiers and police joined forces to strike swiftly in raids on the south and north sides of Montreal making arrest in separatist areas under the extended provisions of the special war emergencies act. (CP PHOTO/CP)

Close to 500 people were detained. The majority of them were never charged.

Fifty years later there are calls for Ottawa to apologize.

“Well listen, there were measures put in place and people were arrested without cause so I think there should be an apology,” said Premier Fancois Legault.

Robert Comeau, a former member of the FLQ, now a retired university professor also believed the government should issue an apology.

“Their only crime was being pro-independence... In a totalitarian country they put people in prison. In a democracy, there should be a little more respect,” Comeau said.

Others argue that even though they believe the measures were abusive, an apology is not necessary.

“But why the federal government, which is the government of all Canadians, or the Quebec government which participated in this, would now apologize when it’s a completely different assembly, a completely different population, I don’t know,” said human rights lawyer Julius Grey.

When asked recently about an apology Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said, “There's no question that the events of October 1970 had a difficult impact on many Quebeckers, but I think we need to remember first and foremost that this particular anniversary is going to be very difficult for the families of Pierre Laporte.”