MONTREAL -- Working in child protection is working with adversity. Child protection practitioners are in contact with daily suffering, violence, neglect, abandonment... and all the horror that we hardly dare to imagine.

Studies show that practitioners who choose to work in child protection services are deeply motivated by the hope of helping vulnerable children and families. Involving themselves body and soul in emotionally demanding work, a majority develop a sense of compassionate satisfaction.

Making a difference for the populations they serve is often the driving force that allows workers to continue this important mission despite the adversity they encounter.

But working with traumatized populations also has its share of consequences -- post-traumatic stress disorder, burnout, depression, etc. - and it is essential to bring awareness to these consequences.

Child protection professionals are at risk of presenting not compassion satisfaction, but rather compassion fatigue.

An even more important stressor affecting their mental health is the accountability that forces them to justify their actions to their clients, their institution, the court, public opinion, but especially to their own conscience. When interviewed, workers raise a shared and omnipresent fear of finding one of their files in the media and being blamed for professional errors. While this accountability is necessary to prevent further harm to children and their families, the stress associated with it weighs heavily on their shoulders.

Moreover, there is a professional culture that trivializes the psychological consequences of child protection work. This culture has existed for several years and conveys the idea that dealing with this suffering is "part of the job."

When such a belief persists, it is difficult to seek professional help, or to talk about it with colleagues or superiors, for fear of being stigmatized as incompetent. Studies point out that workers in distress are more likely to become isolated and not seek help.

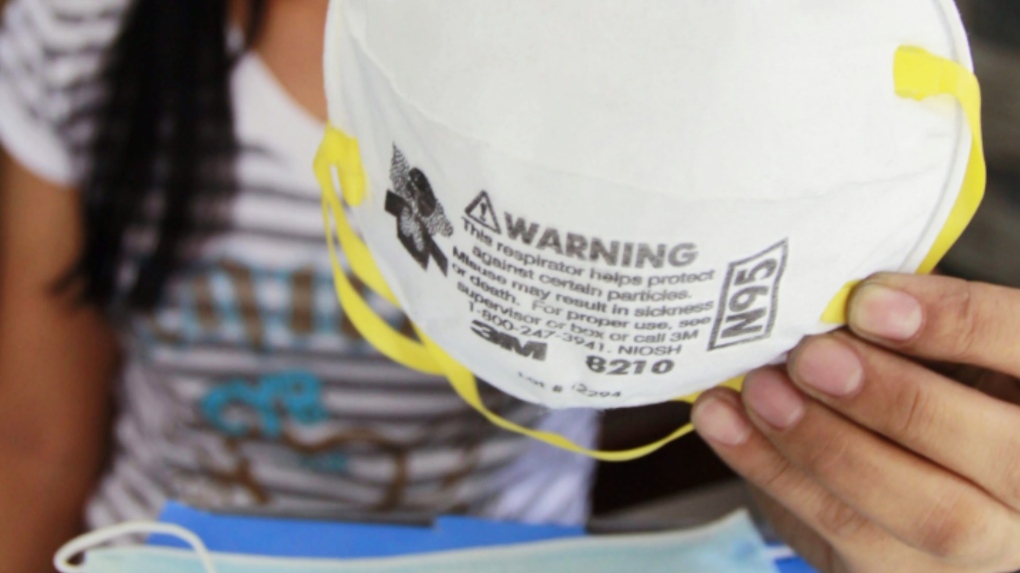

Getting support is vital for child protection workers. Yet, as privileged partners in this network, we regularly find that support is absent. Working in child protection services is like being assigned to the COVID case floor at the hospital, but without the protective gear, without N-95 masks, and without a public discourse that sees us as "guardian angels."

It is not a virus that is likely to affect these workers, but rather the human suffering they must deal with every day and the fear of committing a mistake that could cost a child his or her life. It is imperative to prioritize the psychological health of youth protection workers because they are the foundation of the protection of vulnerable youth.

Unfortunately, through the reforms, this foundation has eroded with time. The Laurent Commission has exposed the flaws of this system which lacks resources to help children and families in youth protection, but also to support their workers. Numerous recommendations will be made in the Commission’s report expected this spring, and we hope that they will give an important place to the practitioners who are key actors of this network. We must understand that no reform will change the fact that without these practitioners, there would be no real collaborative work with families, no real work to rehabilitate children in difficulty.

What are we waiting for to provide our child protection teams with the resources they need to be supported? It is time to stop ignoring the suffering of these practitioners. It is time to take care of them so that they can continue to take care of others.

There may be no N-95 masks to protect against compassion fatigue, but solutions do exist, and research shows their positive impact on workers’ well-being -- including trauma-focused training to better address their clients’ complex needs, communities of practice, ongoing monitoring of interveners' psychological health, peer support, clinical supervision, review of caseloads. These solutions are promising, simple, and inexpensive and could provide the necessary tools to support child protection workers.

We believe that this transformation can also take place through a change of mentality in society at large. We should start by recognizing that child protection workers are doing a difficult job. If this job seems so intense to us from the outside, then it is time to admit that these workers have every reason to experience sadness, fear, powerlessness, anger, and guilt.

These emotions are signs of their empathy towards their clients and we must understand that their need for rest is legitimate to regain emotional balance.

It is urgent for the media to talk more about their positive accomplishments, to focus on the "good news" from child protection -- because there is some! With this in mind, we tip our hat to child protection workers and feel privileged to collaborate with them.

- Steve Geoffrion is an associate professor at Université de Montréal and Delphine Collin-Vézina is a full professor at McGill University