'One of a kind' Robert Silverman, who reimagined Montreal for cyclists, dies at 88

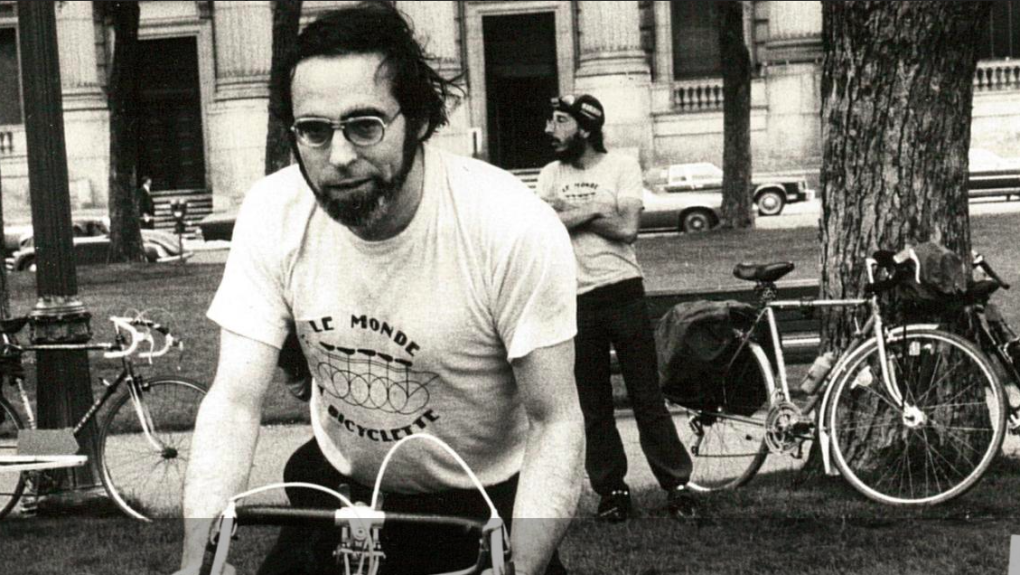

Robert Silverman, pictured around 1980. (Photo: Archives of Le Monde à Bicyclette/Ville de Montreal)

Robert Silverman, pictured around 1980. (Photo: Archives of Le Monde à Bicyclette/Ville de Montreal)

In life, especially when he was young, Robert Silverman was known as an eccentric, even someone who played the clown.

He's being remembered, however, as a visionary who changed life for millions of people by changing the streets around them.

Silverman died on Sunday afternoon at the age of 88, in the care home in the Laurentians where he spent his last year and a half, according to his friend Richard Wutzke.

For decades, he was a larger-than-life figure in Montreal, theatrically defending countless causes -- but none with more reverberations than his bike activism.

"Bicycle Bob," as he was known in the 70s, 80s and beyond, found novel ways to make his point that cycling should be safer and easier, and -- long before climate activism -- that bikes could be embraced to everyone's benefit.

He didn't like that nickname at first, but it grew on him, he told writer Maria Worton in a 2003 interview, at the age of 69. Why? Because he loved bicycles so much.

"The bicycle is a symbol of near perfection in terms of its personal, social and planetary implications," he explained.

"Spatially the car and the city are incompatible since the car takes up so much room, 10 times as much room as the person it moves. It's obvious and grotesque."

He founded the group Le Monde à Bicyclette in 1975. Together, they held the first-ever "die-in" protests, where they'd squirt ketchup on themselves and lie as a group in the road, pretend to be accident victims.

Silverman hand-painted bike lanes on city streets to draw attention to his cause, reportedly once getting arrested for it. He famously dressed up as a Moses of Montreal to demand that the transit authority "part the St. Lawrence" for cyclists by letting them over the bridge to the South Shore with their bikes (he won; they relented).

His relentless push, along with the work of his group and others like it, catapulted Montreal into being ahead of its time, at least on this side of the Atlantic, on installing bike paths and other infrastructure.

But cycling was far from Silverman's only interest. In the same 2003 interview, he recounted how he came to activism in the first place, when someone invited him to join an anti-nuclear protest in 1959.

"I had just quit my father's business, in insurance, I was 26, middle-class, single, no experience," he said.

"How could I refuse? The cause was saving the world. I was walking with people who wanted to save the world. And I felt joy for the first time, de-alienation. It saved my life because I saw a way other than fighting everyone in the dog-eat-dog-save-yourself mentality of my family."

While he chose a different path from his family, he also described many times how his father helped him set up a business -- a bookstore, downtown on Stanley Street -- and he leaves behind a sister to whom he was close, Wutzke said.

He picked a bookstore for his experiment in business, despite having no experience in that field, either, simply because it caught his "imagination," he said in an interview in 1960.

"At times I feel that experience can be a hindrance to new trends and ideas," he told the Canadian Jewish Chronicle.

"I feel that a bookshop should be something beautiful where people don't feel rushed, a place that sets a mood of well-being. My friends thought I was nuts to put chairs here. I don't care if someone reads here for four hours. I don't ever want to become too commercialized."

The bookstore folded, according to the Montreal Gazette, but Silverman was never lacking things to move on to.

Montreal city councillor Peter McQueen, who knew Silverman well and was part of Le Monde à Bicyclette for years, said that his friend's passion and sense of drama never faded, even decades after the height of his bicycle stunts.

"When I went with him and other volunteers on an official cycle tour of Cuba in the early 90s, he was still riding despite his deteriorating vision, and giving 'velorutionary' speeches despite his bad Spanish," McQueen told CTV News.

"Once when we visited a waterfall on what the Cubans considered a cool day, he started giving a speech about the greatness of Cuba while standing on a rock just in front of the waterfall."

Silverman was about 60 at the time, and the "poor freezing Cuban guides" were terrified, McQueen remembered.

One of them got behind Silverman and held the "always young-at-heart Bob by the back waistband of his bathing suit, to make sure he did not fall off the rock and injure himself," he said.

"Everyone who ever met Bob thought he was one of a kind."

In his interview in 2003, Silverman was asked if activism ever got him down.

"Palestine gets me down. Very much so," he answered, describing his trips to the Gaza Strip and the campaigning he'd done there for Palestinians' rights, including meeting with Yasser Arafat.

"And the second thing is Volleyball in the Park, which I co-founded in 1974," he continued.

That was also getting him down, he said, because "in the last year or two [it] has been taken over by evil elements, by which I mean it's become competitive and exclusive, when it used to be social and inclusive," he explained.

He found it especially reprehensible that half the players had been women, and now they were only 10 per cent, he said.

Was it a strange parallel to draw with the situation in Israel and Palestine? It might seem less important, he acknowledged.

"It is apparently frivolous," he said. "But volleyball for me is a symbol, a metaphor for harmony... it used to be for everyone."

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

A small plane crashes into a Brazilian town popular with tourists and the number of dead is unclear

A small plane crashed into a Brazilian town that is popular with tourists on Sunday, killing several people, local officials said.

Can the Governor General do what Pierre Poilievre is asking? This expert says no

A historically difficult week for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and his Liberal government ended with a renewed push from Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre to topple this government – this time in the form a letter to the Governor General.

'I'm still thinking pinch me': lost puppy reunited with family after five years

After almost five years of searching and never giving up hope, the Tuffin family received the best Christmas gift they could have hoped for: being reunited with their long-lost puppy.

Two U.S. Navy pilots shot down over Red Sea in apparent 'friendly fire' incident, U.S. military says

Two U.S. Navy pilots were shot down Sunday over the Red Sea in an apparent 'friendly fire' incident, the U.S military said, marking the most serious incident to threaten troops in over a year of America targeting Yemen's Houthi rebels.

BREAKING NEWS 6 adults, 4 children taken to hospital following suspected carbon monoxide exposure in Vanier

The Ottawa Paramedic Service says ten people were taken to hospital, one of them in life-threatening condition, following an incident of suspected carbon monoxide exposure Sunday morning in the neighbourhood of Vanier.

Big splash: Halifax mermaid waves goodbye after 16 years

Halifax's Raina the Mermaid is closing her business after 16 years in the Maritimes.

OPP find wanted man by chance in eastern Ontario home, seize $50K worth of drugs

A wanted eastern Ontario man was found with $50,000 worth of drugs and cash on him in a home in Bancroft, Ont. on Friday morning, according to the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP).

B.C. mayor gets calls from across Canada about 'crazy' plan to recruit doctors

A British Columbia community's "out-of-the-box" plan to ease its family doctor shortage by hiring physicians as city employees is sparking interest from across Canada, says Colwood Mayor Doug Kobayashi.

It was Grandma, in the cafe with a Scrabble tile: Game cafes are big holiday business

It’s the holidays, which means for many across the Prairies, there’s no better time to get locked in a dungeon with a dragon.