MONTREAL -- Kamala Harris may not have ever claimed she has fond memories of Montreal, or anything approaching nostalgia for Canada—but maybe that’s not the most important question about the years she spent here as a teenager.

What Anu Chopra Sharma’s daughter wanted to know, when Harris rose to prominence a few years ago, was how much Canada had seeped into her bones during those formative years.

So she asked her mother, who went to high school with Harris.

“My daughter asked me the same question,” Sharma says, that’s on many Canadians’ minds now that Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden has picked Harris as running mate.

“How Canadian is she?”

Sharma told her daughter that Harris seemed very Canadian when she knew her, at around age 15 and 16.

“There’s no way I could have told you that she was American,” she said.

“I personally think universal health care is going to be her baby,” said Sharma, if Harris does end up as VP.

“And I think it has to do with the fact that she’s…lived in Montreal and seen what [public health care] can be,” she said. “She got to see the other side of the coin, growing up.”

Another former classmate, Dean Smith, said Harris was a creative thinker and “the way she thinks… she will change America.”

A POLITICALLY CHARGED ERA

If Harris hasn’t spoken or written much about her years in Montreal, it’s not because she was in town at a boring time.

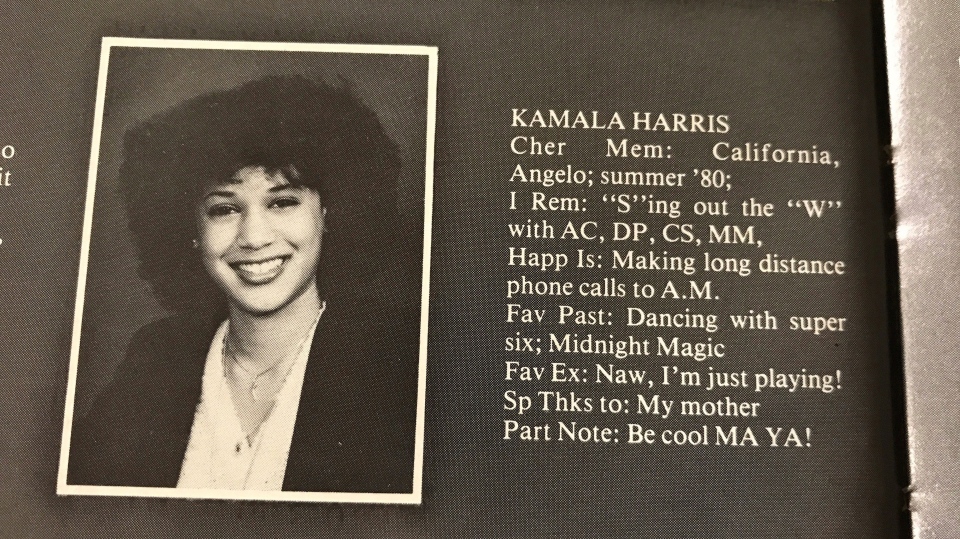

Sharma and Harris both attended Westmount High, a public English-language high school near downtown Montreal, in the late 70s and early 80s. Both graduated in 1981. The school tweeted a message of support Tuesday afternoon when the news about Harris was made public.

Harris moved from California to Montreal at age 12 when her mother, scientist Shyamala Gopalan Harris, got a job researching breast cancer and teaching at McGill University. The girl wasn’t happy about it.

“The thought of moving away from sunny California in February, in the middle of the school year, to a French-speaking foreign city covered in 12 feet of snow was distressing, to say the least,” Harris wrote in her memoir.

She left Canada after graduating from high school, which in Montreal is at around age 16.

Those years happened to be some of Quebec’s most tumultuous, with the province holding its first referendum in 1980 over seceding from Canada.

Westmount High, where Harris landed after struggling in a French-language school, was not representative of the tony, largely white neighbourhood along whose border it lays, said Sharma.

Quebec’s English-speaking population was shrinking and its schools closing, meaning students were suddenly commuting long distances to Westmount High.

“You had a huge melting pot of cultures in that school,” said Sharma, who grew up on Nun’s Island.

There was a group from Montreal’s “east end who were all francophones but spoke English,” she said. “We had the Little Burgundy group of kids,” from a historically Black neighbourhood, and “the Westmount kids.”

It was a politically charged time and school was lively—everyone had an opinion on separation. “I think we all absorbed it,” said Sharma.

Shortly before the girls’ graduation, the school made citywide headlines when some students were caught overcharging their parents for grad tickets in order to raise money for graduation-night pot, Sharma said, laughing. (She didn’t suggest that Harris was part of the scheme.)

'VERY LIBERAL-MINDED'

Quebec must have seemed alien in many ways, but Harris was anything but an outsider, said Sharma.

“She was one of the most focused people I knew,” said Sharma, who took math and French with her. “Always doing something after school, be it a club, be it her dance [troupe], be it going to see a game with somebody. She was always doing something. She never just sat still.”

She was also “a social butterfly” who found a way to relate to all types, said Sharma. “She didn’t snub her nose to anybody.”

Sharma and Harris both came from families that were at least partly of Indian origin—Harris’ mother was Indian, which Sharma knew because she’d seen her picking her up after class.

But it was clear that “she identified more as an African-American than as an Indian,” said Sharma. “She was an African-American, as far as I knew.”

Navigating a dual cultural identity wasn’t necessarily the same then as now. Sharma said that she herself didn’t identify as Indian, though she’d been born in India. Almost all classmates from Indian families tended to meet the wishes of traditional parents, living conservatively, Sharma said. But her own parents were unusually liberal, so culturally she was on a different page.

Divorce in the Montreal Indian community was also taboo then. Sharma knew that Harris’ parents were divorced, which told her that Harris’ mom wasn’t your average Indian mother either, she said.

Harris “was very liberal-minded, and that was one of the things that I liked about her,” she said.

THE REAL CANADA

What Harris took from those four or so years is a different question. At the least, she must know Canadian geography better than most Americans, said James Anderson, a recent Fulbright scholar at Queen's University who studied Canada-U.S. relations.

But she would have seen the outcome of a few policies done differently in Canada, he said, including its immigration system.

“I do think there are some things to learn from Canada,” he said.

Biden, if he wins, could also begin to repair the much-stressed Canada-U.S. relationship without much effort by planning an early state visit to Canada and sending Harris—who Canadians have been quick to claim—in his place, he joked.

Sharma says she’ll be watching. She didn’t follow her classmate’s career until her daughter put two and two together a few years ago, though now, “when I look at her on TV and I see the way she talks and stuff, she’s exactly the same person I knew,” she said.

As a Canadian in the U.S., the tropes can get old, Sharma said: “I’m tired of being told Canadians are so friendly and so nice.”

The truth is more interesting, and Sharma hopes Harris feels the same way she does.

“I hope she has a soft spot for Canada.”

-- With files from The Canadian Press