Black Lives Ruined: The effects of racial profiling by police

Racial profiling is a systemic problem plaguing Montreal police (SPVM), according to a judgement by Superior Court Justice Dominique Poulin.

But what does that mean in the lives of the victims?

This is part one of a CTV News three-part series called Black Lives Ruined: The effects of racial profiling by police.

CTV News spoke to eight Black male Montrealers about how racial profiling has impacted them.

These are their words.

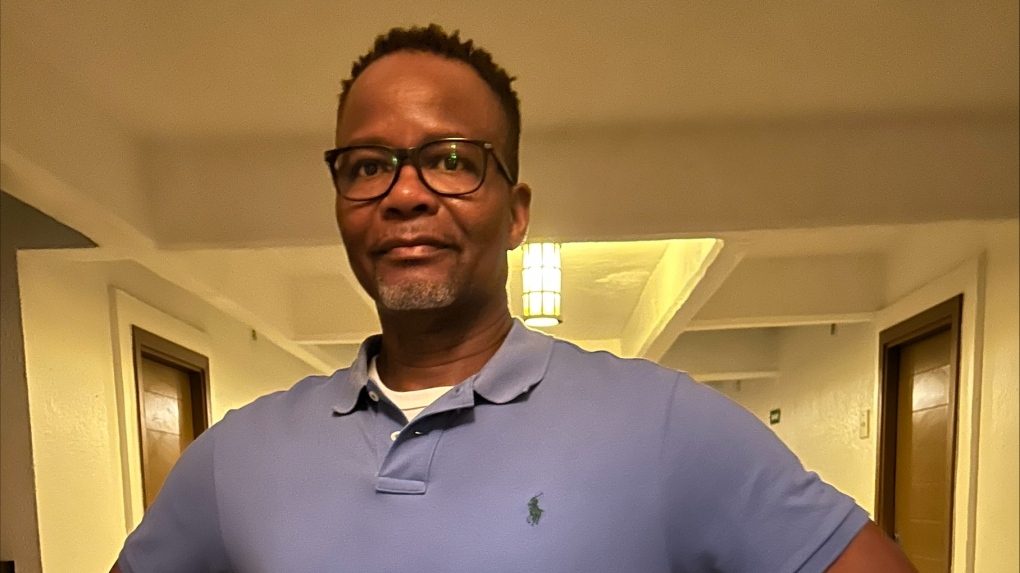

Errol Burke. (Errol Burke)

Errol Burke. (Errol Burke)

Errol Burke

First time stopped by police: 1974

"Many times in my long life, as I look at it now, I've had to deal with being what I always perceived as being persecuted by the police, which amounts to exactly that, being profiled, having been pinned or viewed as someone who's suspicious of doing something, for merely being out in public.

Even though I know, personally, that it actually happens, even I get tired of hearing about it; some people, maybe, to the point where they don't even want to believe it's a thing anymore.

I'm very much hyper-aware about how I'm feeling when I have to encounter the police or if the police are around me because it does have a traumatizing effect.

I very much have a physical reaction to the presence of the police. That's just an acquired reaction over the years.

I'm also very, very concerned about having my phone with me because [the last time] it happened to me, I was out buying milk, and I just left my apartment and said, 'I'm not going to bring my phone, I'm not going to bring my keys.'

The first thing I was thinking was, 'Oh my gosh, I don't have my phone with me' to make sure that I can tape what's happening.

It's a little bit disconcerting that you're always thinking about having this safety device that you need to carry to protect you from the people that you should be thinking are protecting you.

Unfortunately, I go out on the street, and I don't feel like the police are there to protect me. I feel like I need to protect myself from the police, even though that may not be the case.

I'm sure there are plenty of police officers who are fine people, but the institution itself has this problem of defining people based on irrelevant factors like skin colour or culture."

François Ducas. (François Ducas)

François Ducas. (François Ducas)

François Ducas

First time stopped by police: 2017

"If I think about it now, I don't consider myself part of Canadian or Québécois society. I don't feel like an equal citizen. I feel like a number, like a Black person living among white people.

I feel like I'm in a prison, where I'm always being watched. I have to move properly, and even if I do things properly, I could get stopped.

I live with this anxiety.

Sometimes, I think about returning home to Haiti, which the police would probably prefer because that's the message they're sending: you're not from here.

Unfortunately, it's not safe in Haiti, and that's why I haven't returned.

But I'm not the same person; this François Ducas who's happy and maybe a little naive. Over the years, I've become angry, though that anger is slowly starting to disappear.

I don't think about what happened anymore, but I won't ever forget it. I live with it. I've almost become a recluse.

When I'm out, I'm not safe. I have to think before I do anything. I can't be spontaneous.

I live with this anxiety."

-- Translated from French.

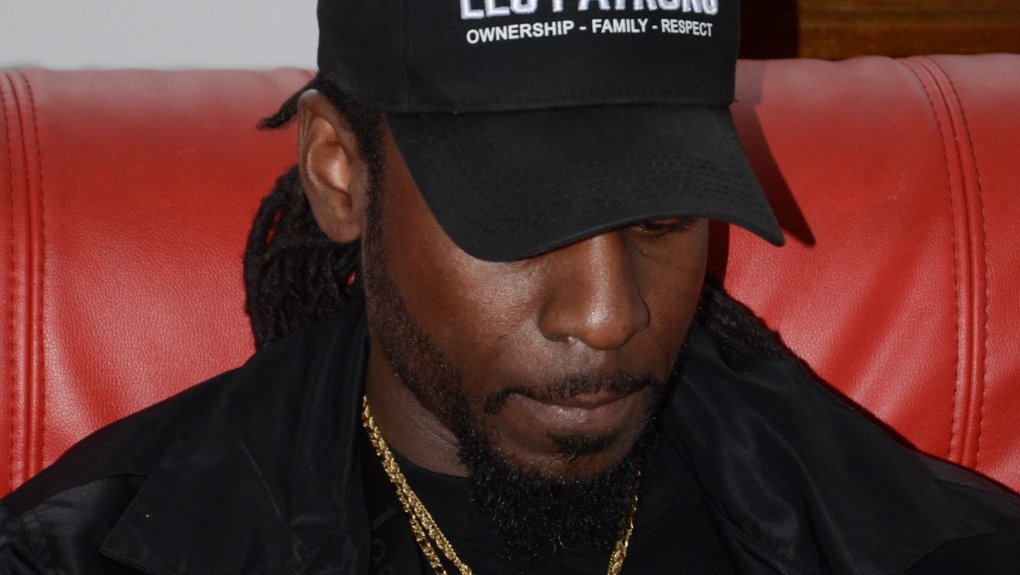

Marcus Gordon (Marcus Gordon)

Marcus Gordon (Marcus Gordon)

Marcus Gordon

First time stopped by police: 2004

"It's just frustrating. You never know what's going to happen. Your safety is always jeopardized by these characters in uniform that are definitely not here to protect and serve us.

Just leave me alone.

I'm trying to live my life and earn a living with everybody else. We're all thrown into this system where we have to acquire food and pay bills.

[One time] I went to work, and while looking for parking, they pulled me over, and they're like, 'licence and registration.'

I was like, 'Is there a reason that I'm being pulled over because I'm literally late for work.'

While I'm explaining this, she [the police officer] does a hand signal, and these two guys pick me up and slam me on the hood [of the police cruiser].

The other gentleman goes around the car and pulls on my head from under my jawline. It's like he's pulling, trying to pull my head off.

While I'm enduring that, they throw me in the back of the car and take me down to the station, charge me with damaging a police vehicle and then they charge me with assaulting officers -- and I lost the case.

[The police are] the last thing I'm trying to think about because I'm about protecting my energy. I'm just focusing on what I've got to do.

I'm really managing how I operate within myself. They just stress and tend to block that frequency from my system.

I can't live in fear anymore.

I refuse to have that mentality because then they're winning. I'm just going to be the best version of myself and not allow them to hinder my experience as much as possible."

Pradel Content. (CTV News)

Pradel Content. (CTV News)

Pradel Content

First time stopped by police: 2012

"The first time I was stopped by police, I was in downtown Montreal. I got stopped three times within the span of an hour. Three times by three different cops.

The third time, I got mad at the cop and told him, 'you guys don't have a police radio? You don't know what guys you pull over? A Black man with an Escalade?'

He just looked at me like I'm crazy. It was the third time. I'm not supposed to act like that, but I did. All those times, I didn't get a ticket or nothing.

I know what living while Black is and driving while Black, but I never got pulled over three times in the span of an hour before I moved back to Quebec [from the U.S.]

I get pulled over; they make U-turns like I just robbed somebody or I committed murder.

It's condescending.

Right now, I stay home and I do the minimum to go out. One minute is the tail light; one minute is which car I'm driving; the next minute, the music is too loud.

I live in hell.

Even when people invite me to go somewhere, I have to think about it because I'm being hawked, and it makes no sense.

(pause)

This is probably the first time I've ever cried talking about when something happened to me like that because it's dehumanizing.

I'm still living this nightmare.

One officer, he told me I'm lucky to be in Quebec because if I was in the States, they'd shoot people like me. I don't feel like a grown man anymore."

Amaëchi Okafor. (Amaëchi Okafor)

Amaëchi Okafor. (Amaëchi Okafor)

Amaëchi Okafor

First time stopped by police: 2021

"Fear. It's mostly fear. It controls my movement now. It's really had a mental drain on me.

It's something you relive every time you see a police car: are they going to be looking?

It's like someone losing the trust. I once had it with the police. I think I lost it.

As a graduate student here, I did a lot of research before coming to Montreal because I was careful about the kind of society I went to for my doctoral studies.

I'm not going to the U.S., so it's scary to try to avoid something, thinking it would be way better in Montreal or in Canada, and coming to see that it's almost the same thing.

If you're going to be coming here, you should be ready for a little bit of racism. You should be aware. You should be ready for it.

I wasn't prepared that way because I actually did my research, but it wasn't obvious that it was this prevalent.

It was a brandishing. It's something I always try to avoid remembering.

My doctorate is supposed to contribute to Quebec, to Montreal, but if I don't feel safe, then I don't think staying in Montreal will be the best-case scenario.

This is the reality of actually being Black, and that shouldn't be a reality in this age and time where everybody knows it's not the right way to treat any human, irrespective of race or gender or nationality or anything at all."

Kwadwo Yeboah. (Kwadwo Yeboah)

Kwadwo Yeboah. (Kwadwo Yeboah)

Kwadwo Yeboah

First time stopped by police: 2000

"When we were younger, I lived in a neighbourhood where it was really a game of cat and mouse with the police.

The last thing somebody wanted is to even see a police car. From a very young age, you see a police car and run.

We know that even though we didn't do anything wrong, we just knew that that encounter was not going to be a good one.

One time, the police just stopped me, asked me for my name. They said I looked like somebody that had committed a crime.

After that, they handcuffed me and drove me all the way to [Rivière-des-Prairies] RDP, which is close to 40 to 50 minutes from my house, and they just left me there.

He's like, 'Good walk back home.'

When I became a lawyer, I'm like, my God, these things haven't changed. Nothing has changed throughout the years. They don't care.

Even though you changed, I don't live in the same area, I don't go to the same places, but guess what? It's still happening to me."

-- Yeboah works as a criminal defence lawyer, defending many cases of racial profiling.

Kenrick McRae. (Kenrick McRae)

Kenrick McRae. (Kenrick McRae)

Kenrick McRae

First time stopped by police: 2010

"I'm fearful, struggling, especially when I leave my home. The police, it's always an intimidation tactic. They keep looking at you.

One white officer called me, 'Boy.' I was twice the age of this officer.

If it doesn't happen to me, it happens to somebody else tomorrow, even though it's highlighted, even though it's reported, even though it made the news.

They still feel comfortable doing what they do.

The first time I was ever stopped by the Montreal police (SPVM) was when I was walking with my two kids. I took them out to get ice cream.

We were walking, and two female white cops, I see they're looking at me all the time, and then they came up to me, and they asked me if these kids belonged to me.

I say. 'Yes. They're my daughters.'

And then, they had to confirm with the kids that these kids are my daughters. That was the first time.

Now it's driving this car, going to work.

They stop me, always ask me whatever foolish questions, like what kind of job I do, where you get money from to buy this car?

Ten minutes into my drive, the police is going to tell me I don't have a licence plate.

I said, 'Sir, the licence plate is right here.'

He had a long night, and he didn't have a cup of coffee. This is the kind of thing that happens to me.

He could have shot me. Let's say it escalated, and he shot me. His excuse was because he didn't have a cup of coffee.

I'm scared, number one. I'm angry that it doesn't seem like the people in authority are really listening.

When you keep denying these facts, the systemic racism shows."

Stanley Jossirain. (Stanley Jossirain)

Stanley Jossirain. (Stanley Jossirain)

Stanley Jossirain

First time stopped by police: 2014

"At first, I didn't know my rights. So, for me, it was all normal; every question they would ask me, I would answer, and I would never go complain at the police station.

There's a bar in Repentigny, [and] at the end of every session, people go there. I went there with some friends, and when we left around midnight, we got stopped.

It was different police cars. At one point, they gave me the OK to leave, and I wanted to go see my friend.

I got out of my car, [and] I went to go to my friend and ask him if he was OK, if he wanted me to stay or just leave.

The next thing you know, there were two police officers who took out their guns and pointed them at me.

That was when it started to really hit me hard.

I wanted help, but usually, when you want help, you call 911, but they were the ones aiming their guns at me for no reason.

I had no one to hear, to scream at when I needed help. I had no one to help me at the moment. It was hard. It was really harsh, too.

When I go out, and I drive, [and] I see a police car, I still get some flashbacks, and I get some emotion, some fear.

I feel vulnerable. I feel like I don't have the same rights as the others. To this day, it still has a stain on me.

If I apply for a job, especially a government job, they see all the documents and everything I went through because it went viral, so for me to get a job, a decent job, it's hard for me."

-- Answers have been shortened for clarity.

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

BREAKING Suspect in killing of UnitedHealthcare CEO will return to New York to face murder charges

The suspect in the killing of UnitedHealthcare's CEO will return to New York to face murder charges after agreeing to be extradited Thursday during a court appearance in Pennsylvania where he was arrested last week after five days on the run.

Potential scenarios for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and the Liberals

The Liberal government was thrown into disarray this week when Chrystia Freeland stepped down from cabinet as finance minister, reviving calls for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to step down or call an election.

Will the Amazon strike impact Canadian deliveries?

As Amazon workers at several U.S. facilities begin a strike, Canadian shoppers are likely wondering how the job action will impact their deliveries.

Google Maps image provides clue in Spanish missing persons case

Chance images captured by a passing Google Maps camera showing a man leaning over a large bag or bags in a car trunk with what could be a human body gave police an extra clue in a murder investigation in the central Spanish village of Tajueco.

Gisèle Pelicot speaks after ex-husband found guilty of rapes, sentenced to 20 years in France

Gisele Pelicot spoke of her 'very difficult ordeal' after 51 men were all found guilty Thursday in the drugging-and-rape trial that turned her into a feminist hero, expressing support for other victims of sexual violence whose cases don't get such attention and 'whose stories remain untold.'

'This shouldn't happen': Calgary family seeks changes after WestJet accessibility incident

A Calgary woman wants WestJet to apologize to her daughter and to improve staff training on accessibility after an incident during their latest trip.

Mystery drone sightings continue in New Jersey and across the U.S. Here's what we know

A large number of mysterious drones have been reported flying over New Jersey and across the eastern U.S., sparking speculation and concern over where they came from and why.

What's the best treatment for ADHD? Large new study offers clues

Stimulant medications and certain therapies are more effective in treating ADHD symptoms than placebos, a new study on more than 14,000 adults has found.

'We'll never be the 51st state,' Premier Ford says following Trump's latest jab

Ontario Premier Doug Ford says Canada will 'never be the 51st state,' rebuking U.S. President-elect Donald Trump’s latest social media post.