After wave of teen arrests tied to organized crime, experts say it's 'nothing new'

After police arrested a dozen teens in the span of a week, parents are worried their kids are being recruited by organized crime groups. But experts say it's nothing new and more prevention work is necessary.

After police arrested a dozen teens in the span of a week, parents are worried their kids are being recruited by organized crime groups. But experts say it's nothing new and more prevention work is necessary.

Parents of Quebec teenagers are worried that high schools are becoming "recruitment grounds" after police arrested a dozen teens it believes have ties to organized crime. But experts say it's nothing new and better prevention measures are needed.

Last week, Montreal police arrested seven teens between the ages of 14 and 17 who allegedly belonged to a gang based in the St-Leonard borough.

Police also arrested a 15-year-old in connection with a weekend arson attempt, and this week, three people aged 17 to 19 years old were arrested in connection with shooting up a building in Old Montreal. Nobody was injured in the shooting.

The targeted building is owned by Montreal businessman Emile Benamor, who also owns two Old Montreal buildings that were hit by suspicious fires — one last week and the other in March 2023. A total of nine people died in the two fires.

One of the suspects arrested in connection with last week's fire is 18.

Police officers were in Old Montreal as a fire broke out on Oct. 4, 2024. One of the suspects arrested is 18. (Cosmo Santamaria, CTV News)

Police officers were in Old Montreal as a fire broke out on Oct. 4, 2024. One of the suspects arrested is 18. (Cosmo Santamaria, CTV News)

There was also the case of a 14-year-old from Saint-Leonard who died in the Beauce region after reportedly being sent to attack a bunker allegedly belonging to a Hells Angels puppet gang in Frampton, Que.

Pietro Bozzo, head of the Maison de la famille de Saint-Leonard, said although a minority of kids are getting involved in crime, it's been giving teenagers in the area a bad reputation.

"It's been very, very emotional for a lot of the families, and especially because it's a close-knit group, everybody knows each other, and word of mouth gets out," he said.

"Nonetheless, here we are, and parents are really at a loss to see how they can control these gangs going in and trying to recruit their teens."

'Loss of confidence'

On Thursday, Montreal Police Chief Fady Dagher called on parents to work with police.

"If officers knock on your door with concerns about your kid being headed for trouble ... don't close the door," he said at a news conference.

However, Pietro said many families might not trust the police or youth protection services.

"There's a sort of a loss of confidence in the ability of the police and the establishment to take care of what they consider pretty serious security problems," he said.

Montreal police Chief Fady Dagher makes a speech after being sworn in during a ceremony on Jan. 19, 2023, in Montreal. Montreal's police chief made a plea Thursday to parents of youth being recruited by criminal gangs: if officers knock on their door with information about their kids heading down the wrong path, please hear them out. (Ryan Remiorz, The Canadian Press)

Montreal police Chief Fady Dagher makes a speech after being sworn in during a ceremony on Jan. 19, 2023, in Montreal. Montreal's police chief made a plea Thursday to parents of youth being recruited by criminal gangs: if officers knock on their door with information about their kids heading down the wrong path, please hear them out. (Ryan Remiorz, The Canadian Press)

Valentin Pereda, an assistant professor at the school of criminology at Université de Montréal, warns against sweeping statements like "we're seeing more street gangs, more youths involved in crime."

"This increased visibility in youth violence or youth involvement in gang activity is actually a side effect of other factors that are not necessarily related to an increase in marginalization or in youth crime," he said.

Though police might make significant arrests targeting criminal organizations, the root causes of crime aren't addressed, said Pereda.

"If the causes of crime remain, then those people will be replaced by somebody else," he said, like someone younger and more reckless.

Changing the rules

Dagher told journalists Thursday that 30 years ago, when he first joined the police forces, "it was the same," but the players and context have now changed.

"It's disgusting to use kids as footsoldiers," he said.

"These kids want to be heard and loved. They're looking for another vibe and criminal groups know how to trap them. They know how to make them feel important," he said.

Experts agree that with crime leaders getting older, the rules and codes groups and gangs live by are changing.

Maria Mourani, a criminologist and the head of Mourani Criminologie, said organized crime groups aren't "becoming more disorganized," as Public Security Minister François Bonnardel suggested at a news conference Friday.

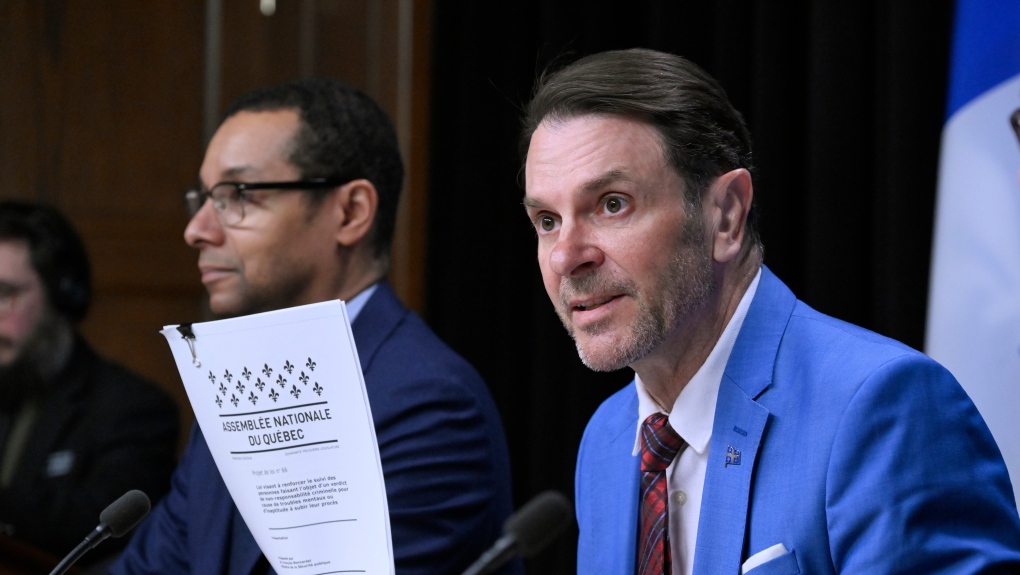

Public Safety Minister François Bonnardel wants to give police more funding to tackle organized crime. (Jacques Boissinot, The Canadian Press)

Public Safety Minister François Bonnardel wants to give police more funding to tackle organized crime. (Jacques Boissinot, The Canadian Press)

Kids as young as 11 years old have always been recruited into criminal groups, said Mourani, adding, "It's not new."

She said that from the mid-2000s until right before the pandemic, Montreal's criminal ecosystem had a certain balance because of alliances between the Hells Angels, the Italian Mafia and "OGs." They typically resolved conflict quickly and quietly.

"The new generation is breaking the rules," she said. "They don't want to work for the bikers anymore," and that makes it more likely for them to get caught.

Better prevention measures needed

Bonnardel boasted to journalists that the Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) government made massive investments in police corps since coming into power, "more than any other provincial administration." These investments allowed thousands of new officers to join the ranks.

But Mourani said that money is going to waste because not enough attention is paid to preventative measures, and the ones in place aren't always targeting the right kids.

She said it's true that schools are recruitment grounds for gangs — and always have been — because that's where kids are, and that's where the resources need to go.

"Kids who are in gangs or vulnerable, they're in schools. Schools have to get specialists in gang activity," she said.

Criminologist Maria Mourani said more resources need to be dedicated to schools and families to protect kids from being recruited by criminal organizations and gangs.

Criminologist Maria Mourani said more resources need to be dedicated to schools and families to protect kids from being recruited by criminal organizations and gangs.

Bozzo of Maison de la famille Saint-Leonard echoed the sentiment. He said that though his organization and others like his set up youth programs, the teens more likely to sign up "are not necessarily the teens that might get involved with the underbelly of the streets."

"Even though we do set up these programs, I don't know if they're as effective as they could be," he said.

Mourani believes that the focus should not only be on schools but also families themselves.

"These kids at age 12 aren't looking for money, they're looking for love. That means the family has failed them, and it has to be said and addressed," she said.

But focusing on repression without giving resources to families or schools is a "fatal mistake," according to Mourani.

With files from The Canadian Press

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

opinion Tom Mulcair: Prime Minister Justin Trudeau's train wreck of a final act

In his latest column for CTVNews.ca, former NDP leader and political analyst Tom Mulcair puts a spotlight on the 'spectacular failure' of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau's final act on the political stage.

B.C. mayor gets calls from across Canada about 'crazy' plan to recruit doctors

A British Columbia community's "out-of-the-box" plan to ease its family doctor shortage by hiring physicians as city employees is sparking interest from across Canada, says Colwood Mayor Doug Kobayashi.

'There’s no support': Domestic abuse survivor shares difficulties leaving her relationship

An Edmonton woman who tried to flee an abusive relationship ended up back where she started in part due to a lack of shelter space.

opinion King Charles' Christmas: Who's in and who's out this year?

Christmas 2024 is set to be a Christmas like no other for the Royal Family, says royal commentator Afua Hagan. King Charles III has initiated the most important and significant transformation of royal Christmas celebrations in decades.

Baseball Hall of Famer Rickey Henderson dead at 65, reports say

Rickey Henderson, a Baseball Hall of Famer and Major League Baseball’s all-time stolen bases leader, is dead at 65, according to multiple reports.

Arizona third-grader saves choking friend

An Arizona third-grader is being recognized by his local fire department after saving a friend from choking.

Germans mourn the 5 killed and 200 injured in the apparent attack on a Christmas market

Germans on Saturday mourned the victims of an apparent attack in which authorities say a doctor drove into a busy outdoor Christmas market, killing five people, injuring 200 others and shaking the public’s sense of security at what would otherwise be a time of joy.

Blake Lively accuses 'It Ends With Us' director Justin Baldoni of harassment and smear campaign

Blake Lively has accused her 'It Ends With Us' director and co-star Justin Baldoni of sexual harassment on the set of the movie and a subsequent effort to “destroy' her reputation in a legal complaint.

Oysters distributed in B.C., Alberta, Ontario recalled for norovirus contamination

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency has issued a recall due to possible norovirus contamination of certain oysters distributed in British Columbia, Alberta and Ontario.