Why does a Montreal park have a plaque in French and Esperanto?

There is a plaque at the entrance to a small park in Montreal's Plateau that honours a Quebec workers' rights activist who learned a second language in the late 1800s and worked to spread it in the province.

That language was Esperanto, and the plaque at the entrance of the Parc Albert Saint-Martin includes in inscription in the invented language as well as French.

"Omago al Albert Saint-Martin, Pioniro de Esperanto en Montrealo," the plaque reads. (In honour of Albert Saint-Martin, pioneer of Esperanto in Montreal).

"Albert Saint-Martin was really a man who dedicated his whole life to help workers," said Norman Fleury, who helped organize the World Esperanto Conference in Montreal in 2022.

A plaque at the entrance of Albert Saint-Martin Park includes an inscription in both French and Esperanto, celebrating the workers' rights activist from the 1800s. (Daniel J. Rowe/CTV News)

A plaque at the entrance of Albert Saint-Martin Park includes an inscription in both French and Esperanto, celebrating the workers' rights activist from the 1800s. (Daniel J. Rowe/CTV News)

Saint-Martin, Fleury explained, founded cooperatives, libraries, and educational facilities for workers and was also an early convert to Esperanto.

"He actually learned Esperanto seven years after the creation of Esperanto in 1894," said Fleury. "He thought that this idea to have a common language for workers was a really good idea... He was really a pioneer to create an Esperanto movement in Canada."

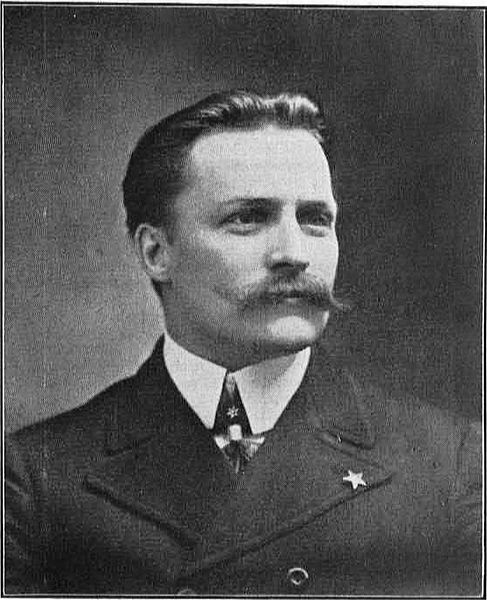

Workers rights activist Albert Saint-Martin was a leading Quebec socialist who worked to spread Esperanto in the late 1800s and early 1900s. SOURCE: Wikicommons

Workers rights activist Albert Saint-Martin was a leading Quebec socialist who worked to spread Esperanto in the late 1800s and early 1900s. SOURCE: Wikicommons

At the time, Fleury explained, many immigrant workers came to Quebec from European countries and did not speak English or French, so Saint-Martin hoped Esperanto would be a language that all could learn and speak.

Saint-Martin attended the first World Esperanto Convention in 1905 in France. In addition to having a park named after him, the University of Quebec at Montreal (UQAM) socialist student group commissioned a tribute mural to Saint-Martin which overlooks Parc Gilles-Lefebvre.

The Tribute to Albert Saint-Martin honours the workers rights activist from the late 1800s and early 1900s and overlooks Parc Gilles-Lefebvre in Montreal's Plateau. (Daniel J. Rowe/CTV News)

The Tribute to Albert Saint-Martin honours the workers rights activist from the late 1800s and early 1900s and overlooks Parc Gilles-Lefebvre in Montreal's Plateau. (Daniel J. Rowe/CTV News)

The plaque honouring him was installed after around 800 Esperanto speakers came to Montreal for the 107th annual event in 2022.

"It was awesome," said Quebec Esperanto Society president Nicolas Viau. "We'd been talking about it for the better part of a decade. That's a long time to be waiting for an event to happen."

The Quebec Esperanto Society includes around 200 people who meet monthly to speak and promote the language.

The 107th World Esperanto Conference was held in Montreal in 2022. SOURCE: Quebec Esperanto Society

The 107th World Esperanto Conference was held in Montreal in 2022. SOURCE: Quebec Esperanto Society

A NEUTRAL LANGUAGE IN AN UNEQUAL TIME

Jewish Polish doctor Ludwik Lejzer Zamenhof created the language in 1887, hoping to add a neutral language in Europe that discarded status or hierarchy.

"Because Latin was really hard to learn, and he wanted to have a neutral language so that doctors around the world could learn this language and communicate," said Fleury. "But it wasn't the doctors that did learn it, but ordinary people, so the language spread out really fast."

Neutrality was important for Zamenhof. Viau explained that as a Jewish person living in Poland at that time, Zamenhof would have experienced a lot of inequality and prejudice.

"This pushed him to create a tool for people to better understand each other, to bridge differences, to allow people to communicate without one bowing to the other essentially," said Viau.

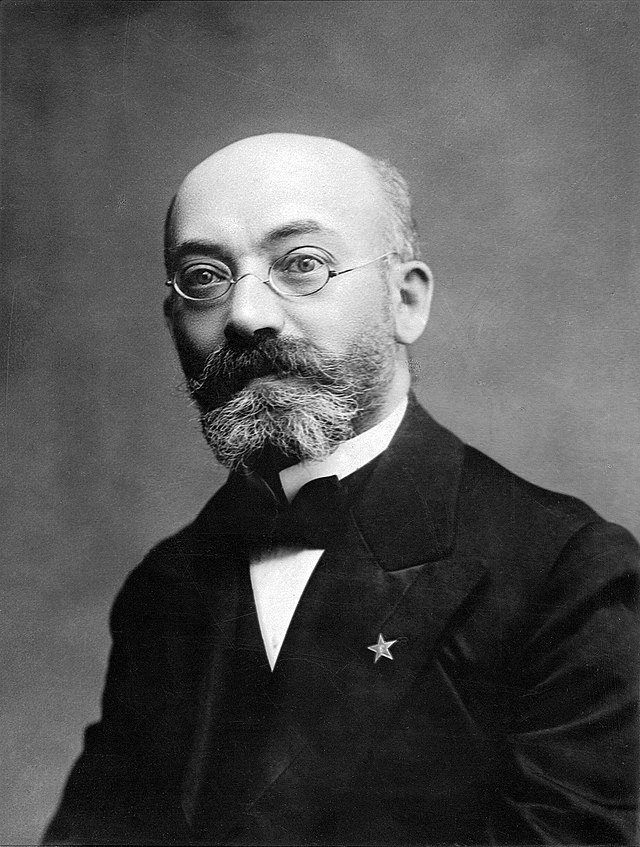

Ludwik Lejzer Zamenhof created Esperanto in 1873 as a neutral language based on Latin. SOURCE: Wikicommons

Ludwik Lejzer Zamenhof created Esperanto in 1873 as a neutral language based on Latin. SOURCE: Wikicommons

EASY TO LEARN

Learning the language, Fleury explained, is relatively simple.

"Esperanto is very easy to learn because out of one root, you can create many words," he said.

For example, in English, the words horse, mare, steed, equestrian, riding, and such all relate to the base word of horse.

In Esperanto, ĉevala (equestrian), ĉevalo (horse), ĉevalino (mare), ĉevaleto (pony) and other words come from the base: ĉeval

In addition, Fleury said those who speak the language are almost always non-native speakers of it.

"If you use Esperanto with Japanese people or Brazilian folks, then they made the same effort as you did to learn another language," said Fleury, who began learning Esperanto in 1979. "It's not their native tongue, it's not my native tongue, we're more on an equal level."

Fleury met his wife Zdravka Metz, originally from Croatia, at an Esperanto convention, and they speak the language at home.

"It's our common language," said Fleury. "It's neutral for both of us so we always use it with our children."

Normand Fleury and Zdravka Metz met at a World Esperanto Conference. Despite the couple's native languages being French and Croatia respectively, they speak Esperanto as a common language at home. (Daniel J. Rowe/CTV News)

Normand Fleury and Zdravka Metz met at a World Esperanto Conference. Despite the couple's native languages being French and Croatia respectively, they speak Esperanto as a common language at home. (Daniel J. Rowe/CTV News)

Viau, Fleury, and many of those who learn Esperanto speak multiple other languages. Fleury said his children speak French, English, Croatian and Esperanto and Viau feels confident speaking five languages.

Viau began learning the language in 2009 after being drawn to the idea of a neutral language.

"It puts everyone on a level playing field in terms of languages," he said. "Obviously, language issues are very big in Quebec. I speak French; I care about the status of the French language in Quebec, [and] that was the first spark that got me into these kinds of topics.

"When you use Esperanto, for me at least, you can be yourself. The fact that you don't have to use the language of another people, typically in a lot of places a more powerful nation or people, opens you up to the individual in front of you."

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Raised in Sask. after his family fled Hungary, this man spent decades spying on communists for the RCMP

As a Communist Party member in Calgary in the early 1940s, Frank Hadesbeck performed clerical work at the party office, printed leaflets and sold books.

Bird flu, measles top 2025 concerns for Canada's chief public health officer

As we enter 2025, Dr. Theresa Tam has her eye on H5N1 bird flu, an emerging virus that had its first human case in Canada this year.

DEVELOPING Body found in wheel well of plane at Maui airport

A person was found dead in the wheel well of a United Airlines flight to Maui on Tuesday.

Police identify victim of Christmas Day homicide in Hintonburg, charge suspect

The Ottawa Police Service says the victim who has been killed on Christmas Day in Hintonburg has been identified.

Christmas shooting at Phoenix airport leaves 3 people wounded

Police are investigating a Christmas shooting at Sky Harbor Airport in Phoenix that left three people injured by gunfire.

Ship remains stalled on St-Lawrence River north of Montreal

A ship that lost power on the St. Lawrence River on Christmas Eve, remains stationary north of Montreal.

Your kid is spending too much time on their phone. Here's what to do about it

Wondering what your teen is up to when you're not around? They are likely on YouTube, TikTok, Instagram or Snapchat, according to a new report.

Bird flu kills more than half the big cats at a Washington sanctuary

Bird flu has been on the rise in Washington state and one sanctuary was hit hard: 20 big cats – more than half of the facility’s population – died over the course of weeks.

6,000 inmates stage Christmas Day escape from high-security Mozambique prison

At least 6,000 inmates escaped from a high-security prison in Mozambique's capital on Christmas Day after a rebellion, the country's police chief said, as widespread post-election riots and violence continue to engulf the country.