'They didn't want to help': Teen with ADHD says Marianopolis College denied her right to accommodation

For years, 17-year-old Katrina's ADHD flew under the radar.

Despite difficulty concentrating, young Katrina* was a star student. She recounts re-teaching herself the material at home after spacing out in class, determined to get up to speed -- and beyond.

But when high school rolled around and the schoolwork piled up, Katrina's mother, Helen Brindalos, said the symptoms became impossible to ignore.

In Grade 8, she was officially diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Brindalos said the response at her daughter's Montreal high school was swift. Katrina was granted several accommodations to help her keep up, including the option to type in-class essays on a computer rather than write them by hand.

The hope was to secure a similar arrangement at college.

But the process would be far rockier than Katrina expected -- culminating in a months-long clash between her parents and the school, tens of thousands of dollars in legal fees, and a complaint with Quebec's youth rights commission.

'WE WERE LIED TO'

Katrina spoke to CTV News in June, fresh out of her college exams.

In Quebec, students graduate high school in Grade 11 and go to general and vocational colleges, called CEGEPs, before moving on to university. Katrina's CEGEP of choice is Marianopolis, a private, prestigious college in the Montreal-area municipality of Westmount.

"I heard Marianopolis is a small school, so I liked that it wasn't too big, not too many people. That there was this proximity with the teachers, so I knew that if I ever needed anything, I can go see them," Katrina said on her decision to enroll.

Marianopolis granted Katrina some accommodations, such as extra time on her exams. But her request to type in-class essays on a computer -- like she did in high school -- was repeatedly denied.

Katrina said her ADHD makes writing particularly challenging. Connecting ideas is a struggle and her in-class essays often go unfinished, even when she's given extra time.

"I just always have thousands of ideas at once, and I can't seem to always choose. I always change my mind -- I have to put things in order."

Using a word processor like Microsoft Word helps her synthesize ideas more efficiently and keep up with the other exam-takers, she explained, specifying that the computer would not have access to the internet or other tools.

Katrina says typing her exams rather than writing them by hand makes it easier to synthesize information and complete her work on time -- something she struggles with because of her ADHD.

Katrina says typing her exams rather than writing them by hand makes it easier to synthesize information and complete her work on time -- something she struggles with because of her ADHD.

Marianopolis declined a request for an interview, but said in a statement to CTV News that Katrina's request was rejected due to a lack of supporting documentation.

"The student later asked to receive additional accommodations that were not supported by the documentation initially provided. Additional documentation was eventually provided by the student and she received the additional accommodations," the statement reads.

But Katrina and her mother say there's more to the story.

According to them, Marianopolis refused to grant the accommodation because Katrina's writing scores didn't fall below the 25th percentile.

The CEGEP allegedly claimed this was a criterion established by Quebec's Ministry of Education and that the school could be fined if it did not comply.

But when Brindalos reached out to the ministry to confirm, she received a different answer.

"That criteria that [Marianopolis] was basing [itself] on does not exist," said Brindalos, who forwarded her correspondence with the education ministry to CTV News.

"We were lied to."

In a separate email to CTV News, a ministry spokesperson also confirmed that "no, this is not a criterion known to the ministry."

"Institutions are autonomous in their choice of measures. However, the measures must respect the student's right to equal opportunity," the statement added. "Measures must meet the needs of the student and be agreed as part of an individualized intervention plan."

Marianopolis declined to answer specific questions about the alleged 25th percentile criterion and whether it was used as part of Katrina's assessment.

TOO CLEVER FOR A COMPUTER?

Katrina said testing her writing skills misses the point all together because she doesn't have a writing disability.

"I don't make spelling mistakes, I can write words. I can write a text. It's the organizing, the way my brain functions -- that's the part of ADHD that affects me in my writing," she said.

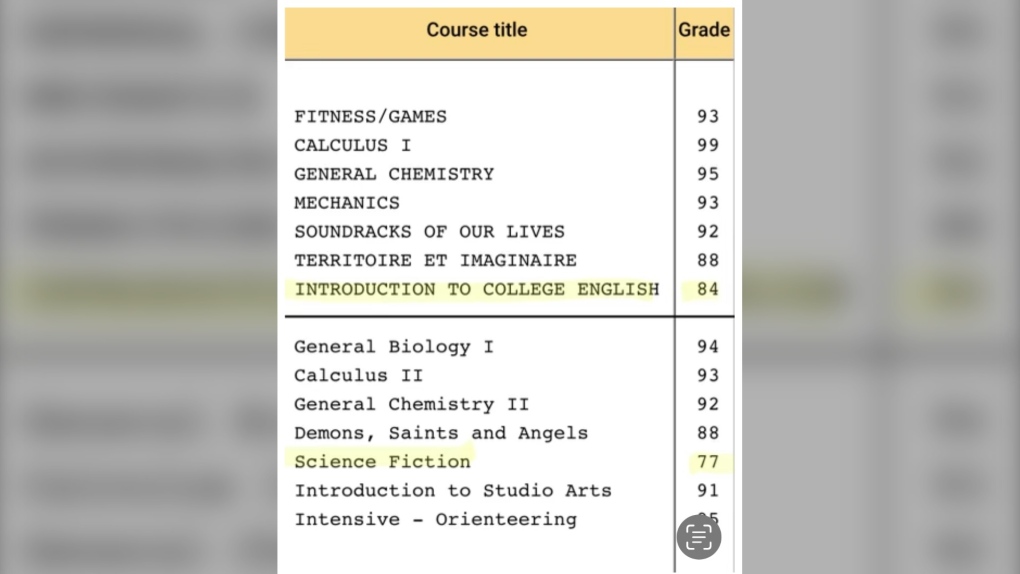

With the exception of English classes, Katrina is a nearly straight-A student. She believes she wasn't taken seriously by Marianopolis because of her high marks -- marks she says she must work three times harder for.

"If I can do better, why shouldn't I be allowed to? It's not giving me an unfair advantage; I'm at a disadvantage now."

She compares it to walking up the stairs with one leg while everyone else has two.

"The person without a leg can't get up the stairs easily. He may be able to make it up if he takes his time and struggles the whole way up, but it's not going to be easy," she described.

"If they were to ask, 'Oh, can I use the elevator' -- would you tell them no?"

Heidi Bernhardt is the founder of CADDAC, a national charity that runs ADHD support programs and advocates for the rights of student's with the disorder.

Heidi Bernhardt is the founder of CADDAC, a national charity that runs ADHD support programs and advocates for the rights of student's with the disorder.

Heidi Bernhardt is the founder and executive director of the Centre for ADHD Awareness Canada (CADDAC).

While she couldn't comment on Katrina's case specifically, she said misconceptions about ADHD often prevent students from getting the help they need.

"When they state something like, 'You're smart, so you wouldn't need this,' it is a clear red flag that they do not understand ADHD, they do not understand disability, and they do not understand a student's right to accommodations when they have a disability," Bernhardt told CTV News.

She stressed that many high-achieving children have ADHD, and that accommodations help them express the knowledge they otherwise struggle to convey.

"She's probably running out of time. Being able to put the content she has or that she's learned that's in her brain -- she can't get it all down on paper," she continued.

"Her being bright has nothing to do with it. ADHD has nothing to do with IQ."

Herself a mom to three sons with ADHD, Bernhardt said denying appropriate and reasonable accommodations to affected students is a "human rights violation."

"It is well documented that students with ADHD have the right to accommodations, and a very frequent accommodation is access to a computer to be able to write exams," she said.

A comparison of Katrina's grades between her first and second semester of CEGEP, showing a drop in a course where writing is involved.

A comparison of Katrina's grades between her first and second semester of CEGEP, showing a drop in a course where writing is involved.

Katrina argues that the difference a word processor makes is reflected in her English marks, which dropped 10 per cent between her first and second semester of CEGEP -- while her averages in other classes stayed roughly the same, transcripts show.

She didn't finish a single one of her in-class English essays last semester, Katrina claimed.

"Each time, I'd lose marks just because it was incomplete," she said.

"I really feel like my grades really were affected."

A MONTHS-LONG BATTLE

Marianopolis held firm to its decision for many months, despite multiple meetings with Katrina and her parents and an official complaint letter filed with the Dean.

Brindalos also forwarded letters to the CEGEP from Katrina's psychologist and psychiatrist to substantiate her needs, but with little success.

The letters, reviewed by CTV News, confirm Katrina's ADHD diagnosis and highlight her struggle to sort her thoughts when writing.

Katrina, who turns 18 in August, says she didn't feel heard by the school's accommodations department or its administration.

"I feel like they didn't want to help," she said, describing an evaluation process that felt brief and impersonal.

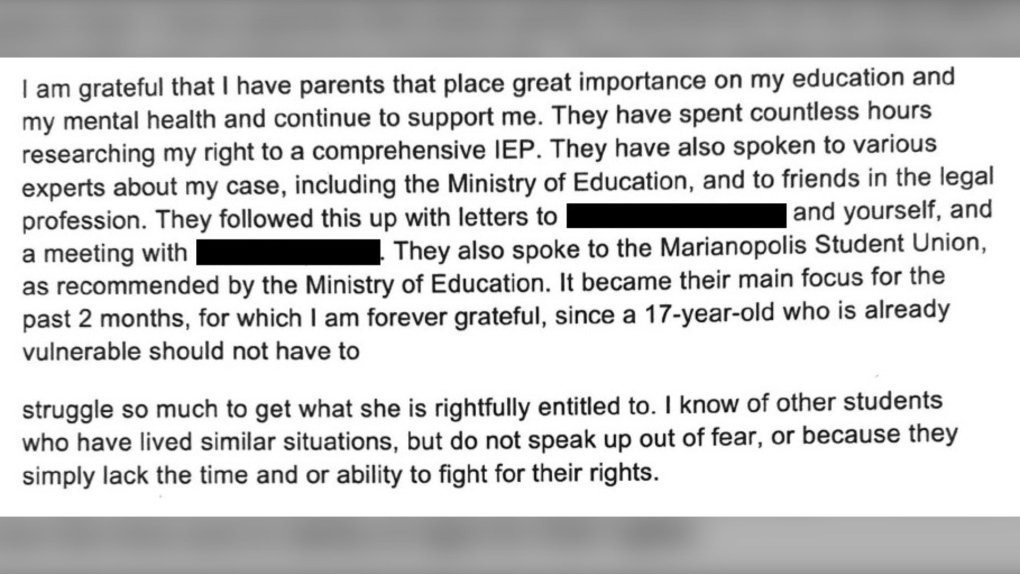

An excerpt from Katrina's complaint letter to the Dean of Marianopolis regarding her struggle to obtain use of a word processor as part of her individual education plan.

An excerpt from Katrina's complaint letter to the Dean of Marianopolis regarding her struggle to obtain use of a word processor as part of her individual education plan.

She says things only started moving in late February when her parents got lawyers involved and filed a complaint with the Commission des droits de la personne et des droits de la jeunesse (CDPDJ), Quebec's human and youth rights tribunal.

"The only reason I ended up getting them, months later, was because my parents got involved, with lawyers, $30,000-plus later."

While taking this step accelerated tensions between the family and the school, Brindalos said they had exhausted every option.

"A child who has an issue at school doesn't have very many ways of navigating the system," she said, noting that Katrina is still underage.

Helen Brindalos (right) has filed a complaint with the CDPDJ, claiming the her daughter's rights as a student with a disability were not respected by Marianopolis College.

Helen Brindalos (right) has filed a complaint with the CDPDJ, claiming the her daughter's rights as a student with a disability were not respected by Marianopolis College.

The complaint with the CDPDJ is under review and will soon enter the mediation phase.

Marianopolis said it "intends to fully cooperate" with the process and "show that the College's actions were appropriate in the circumstances."

DAWSON JOINS THE DISCUSSION

In March, Marianopolis made a proposal: have Katrina's ADHD needs evaluated by a different CEGEP instead.

According to Brindalos, the school wanted to bring a "neutral" party into the fold as the situation had grown increasingly contentious.

After some thought, the family agreed to have Katrina assessed by an accommodations counsellor at Dawson College. Katrina says the process was night-and-day compared to her experience at Marianopolis, describing it as more thorough and flexible.

"My mom was allowed to come with me, too, they didn't have any issues with that," she said.

Dawson ultimately concluded that Katrina should be given permission to type her in-person exams.

In a letter to Katrina's family, Marianopolis' lawyers said the school was "not entirely in agreement" with Dawson's assessment but agreed to follow its recommendation -- with some conditions.

Among them was a request to sign a confidentiality agreement, which the family refused.

"I said, 'Are you kidding me? You're gonna add conditions now that she was fairly evaluated because you want to negotiate with me now?' That's completely unacceptable," Brindalos recalled.

In a second letter, Marianopolis retracted its confidentiality request -- but suggested Katrina attend a different school next semester.

"In the circumstances, our client strongly encourages your clients to find another college for [Katrina's] second year of college studies. While [Katrina] is certainly a bright student with a promising future, it appears that Marianopolis cannot meet her parent's expectations. They should therefore try to find a college that will," it reads.

The CEGEP declined to answer specific questions about either of these letters.

Katrina said the school's message was harsh, but that it wouldn't change her mind.

"I'm not changing schools, I'm not leaving. I'm not going anywhere. I don't care if you think it's better for me, I think it's better for me that I stay."

Marianopolis College is pictured in this file image.

Marianopolis College is pictured in this file image.

In its statement to CTV News, Marianopolis said it follows "well-established procedures and regulations" to establish accommodations following a "detailed analysis."

"Marianopolis College provides students who have documented disabilities with a variety of accommodations. In fact, approximately 200 students receive accommodations from the College in a typical year," it reads.

"The vast majority of Marianopolis students that work with our team of experts for their accommodation needs are extremely satisfied with the services they receive."

*Katrina requested that we use a pseudonym in this report to protect her from potential discrimination by employers and schools.

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

W5 Investigates A 'ticking time bomb': Inside Syria's toughest prison holding accused high-ranking ISIS members

In the last of a three-part investigation, W5's Avery Haines was given rare access to a Syrian prison, where thousands of accused high-ranking ISIS members are being held.

'Mayday!': New details emerge after Boeing plane makes emergency landing at Mirabel airport

New details suggest that there were communication issues between the pilots of a charter flight and the control tower at Montreal's Mirabel airport when a Boeing 737 made an emergency landing on Wednesday.

BREAKING Supreme Court affirms constitutionality of B.C. law on opioid health costs recovery

Canada's top court has affirmed the constitutionality of a law that would allow British Columbia to pursue a class-action lawsuit against opioid providers on behalf of other provinces, the territories and the federal government.

Cucumbers sold in Ontario, other provinces recalled over possible salmonella contamination

A U.S. company is recalling cucumbers sold in Ontario and other Canadian provinces due to possible salmonella contamination.

Irregular sleep patterns may raise risk of heart attack and stroke, study suggests

Sleeping and waking up at different times is associated with an increased risk of heart attack and stroke, even for people who get the recommended amount of sleep, according to new research.

Real GDP per capita declines for 6th consecutive quarter, household savings rise

Statistics Canada says the economy grew at an annualized pace of one per cent during the third quarter, in line with economists' expectations.

Nick Cannon says he's seeking help for narcissistic personality disorder

Nick Cannon has spoken out about his recent diagnosis of narcissistic personality disorder, saying 'I need help.'

California man who went missing for 25 years found after sister sees his picture in the news

It’s a Thanksgiving miracle for one California family after a man who went missing in 1999 was found 25 years later when his sister saw a photo of him in an online article, authorities said.

As Australia bans social media for children, Quebec is paying close attention

As Australia moves to ban social media for children under 16, Quebec is debating whether to follow suit.