MONTREAL -- Outpourings of grief and outrage have rippled across Canada in recent weeks after 215 children's bodies were found on the former site of the Kamloops residential school.

Not much is known or spoken about the government of Canada's 699 Indian day schools (including 54 in Quebec) where about 200,000 Indigenous children attended federally-run schools, mostly operated by various non-Indigenous religious orders such as the Catholic and Anglican Churches.

"More people went to day schools than residential schools and we still know very little about it," said Wahéhshon Shiann Whitebean, who will enter her the third year of her Ph.D. in the fall.

Her research focuses on the 10 day schools that operated at different times in her Kanien'kehá:ka (Mohawk) community of Kahnawake.

About 5,000 Kahnawake students attended day schools run by Catholic or Protestant churches, according to Louise Mayo, who is the coordinator for the Indian day schools class action settlement.

The schools, like residential schools, featured no Indigenous content until the final decades of their operation.

"The only thing Native in the schools were the children," said Kaia’titahkhe Annette Jacobs, who started attending day school in Grade 6 in 1949.

"There was no culture, there were no pictures, there was no singing, there was no dancing, there were no stories. There was nothing that you could identify with as an Onkwehón:we (Indigenous person).

"It was there to change you. There to make you a regular Canadian with no background in your identity."

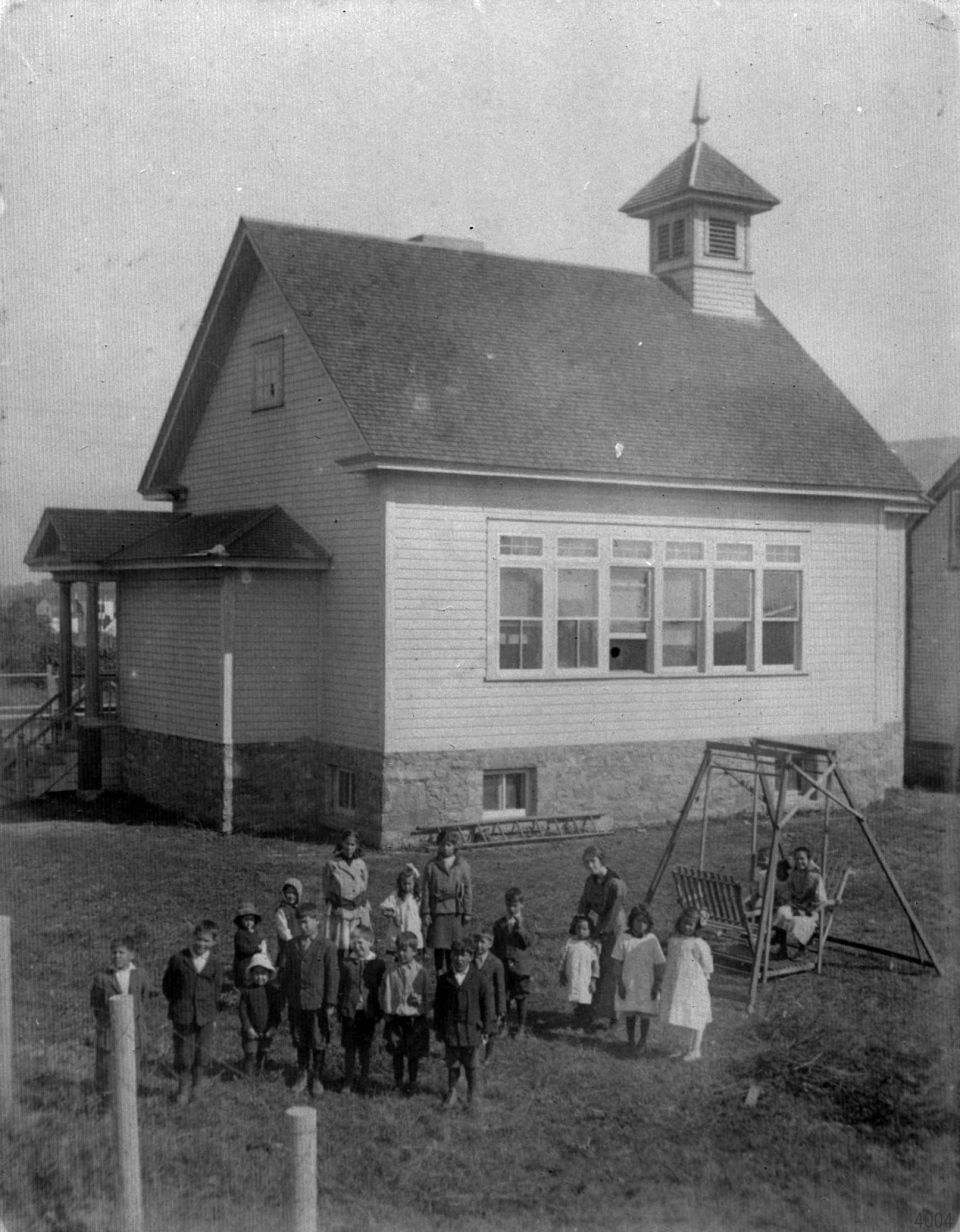

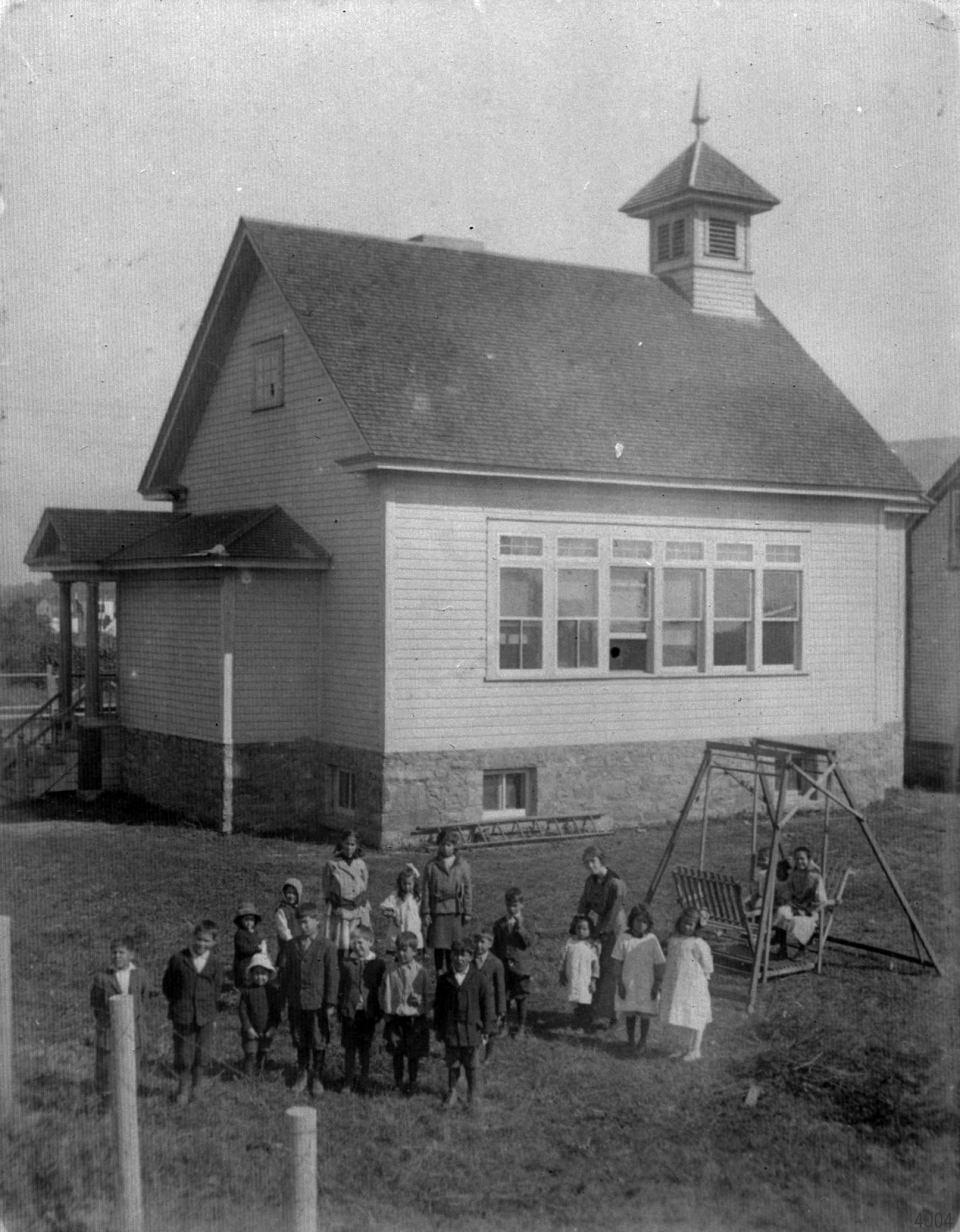

Around 5,000 students from Kahnawake attended one of its Indian day schools that were run by the Catholic and United Churches until 1988. SOURCE: KOR cultural center

INDIAN DAY SCHOOLS SETTLEMENT

Between 1920 and 1988, federally-run day schools operated across the country.

When these day schools were not included in the residential school class action lawsuit, Saulteux Ojibway Garry McLean, from the Lake Manitoba First Nations, spearheaded a $15-billion class action lawsuit against the federal government for the trauma and harm the day school system did to those who attended.

McLean died in 2019 before the suit was settled in 2020 by the law firm Gowling WLG.

Compensation ranged from $10,000 for verbal or physical abuse to a maximum of $200,000 for repeated sexual abuse and/or physical assault leading to long-term injury. Claimants have until July 2022 to file a claim.

Mayo attended Caughnawaga - R.C. (1924-1969), which later became Kateri School, running as a day school until 1988.

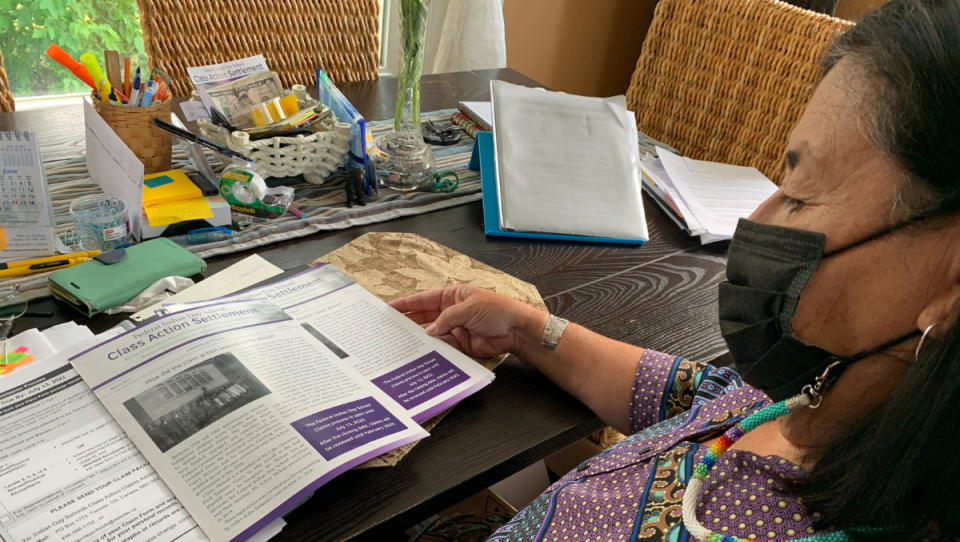

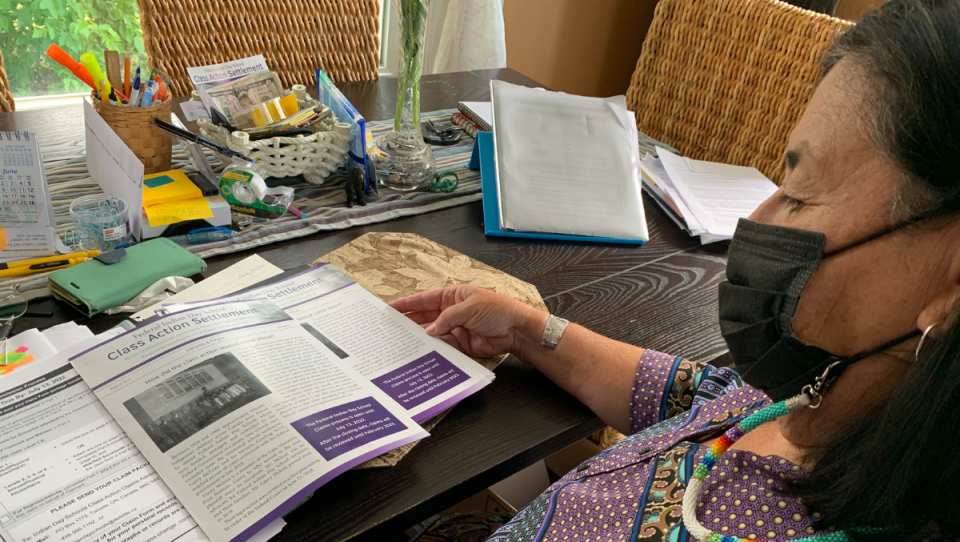

She now helps survivors recount their often traumatic experiences at day schools as they file claims.

"I cry for them," said Mayo. "I empathize with the fact that so many people have carried the shame for so long, and this trauma for so long."

Louise Mayo is the coordinator for the Mohawk Council of Kahnawake responsible for aiding former Indian day school students in completing their claim forms. (Daniel J. Rowe/CTV News)

Kahnawake is one of the few Indigenous communities in Canada with a coordinator to help former students file their complicated 15-page applications. The process often brings up trauma from experiences that are decades old.

"There are as horrific stories as... were addressed and presented at the Indian residential schools," said Mayo. "Everything that happened in residential schools happened in day schools."

Some Indian day schools were small schoolhouses in the farm areas of Kahnawake, while larger ones operated in the heart of the community. SOURCE: KOR cultural center

TRAUMA AT HOME

Listening to former students' stories and helping them recount their trauma for their claims has been emotionally difficult for Mayo.

She said just like residential school survivors, day school students suffered physical, emotional and sexual abuse, as teachers taught students English or French, made them recite the oath of allegiance and other non-Indigenous education, often while abusing students.

"They were so abusive to the students," said Mayo.

"There are so many stories of students' heads being slammed against the table, having been put in the corner, so many shared stories about being sexually abused in the schools."

Being able to go home after school often meant a different type of trauma as they hid their experiences from their parents or elders.

"The only saving grace was that we got to go home," said Mayo. "But even though we got to go home, we carried that trauma with us, we carried that shame."

Mayo, like many of her generation, spoke Kanien'kéha, the Mohawk language, when she started school, but lost it as she aged because she wasn't permitted to speak it at school.

Jacobs’ family spoke the language at home, but she did not teach her children, like many of her generation.

“Now when I think about it, I’m totally embarrassed about it. I didn’t realize what I was doing at the time,” she said. “I was just kind of following what other people were doing… I never even thought of that, but still I didn’t do it.”

Students, Whitebean added, were returning home to communities that had RCMP or Indian agents on the grounds.

"You had RCMP and Indian agents controlling movements on the reserves and in their communities," she said. "So you had a lot of cultural practices prohibited from being practiced publicly."

Wahehshon Shiann Whitebean attended an Indian day school in the final years of their existence and is now working to bring the stories from the era to the public through her research. (Daniel J. Rowe/CTV News)

Though there were multiple day schools in Kahnawake, some parents still were ordered to send their children to the Spanish Indian Residential School in Ontario.

Whitebean said poverty often pushed parents to send their children away, where they thought they would be safe.

The trauma and damage is something, Whitebean said, that lingers and is handed down intergenerationally.

"This is not something we can couch in the past," said Whitebean.

TRANSITION TO IMMERSION

Jacobs may not have taught her children her language, but she taught her granddaughter, who now speaks it fluently.

“I’m so happy because I feel that maybe I’m redeeming myself a little bit,” said Jacobs.

She was also one of those teachers who worked to have her language and culture put back in schools starting in the 1970s.

"We were mandated to teach French, and the parents said, 'Well, if we're mandated to speak French, we might as well teach our own language,'" she said.

The community now has two elementary immersion schools -- Karonhianónhnha Tsi Ionterihwaienstáhkhwa and Karihwanoron -- and Kanien'kéha classes are taught from daycare to post-secondary.

"We're working tirelessly to reform the education system and it's been very effective," said Whitebean. "It's a gradual process."

Whitebean said elders told her the education system forced students to go from speaking their language at home with family to top-down authoritarian instruction in English or French only.

"It's the opposite of who we are and what we teach as Kanien'kehá:ka people," said Whitebean.

"We talk about collective responsibility and knowledge and council process, whereas in a school, the teacher is solely the person there who's the authority figure and you have like a top-down kind of thing that happens in schooling."

Kaia’titahkhe Annette Jacobs spoke her language fluently but did not pass it down to her children, as many of her generation did not. However, she has helped her granddaughter learn to speak it fluently. (Daniel J. Rowe/CTV News)

Jacobs was one of the first teachers, but there are now Kanien'kéha teachers at all levels.

Now, she said, children in Kahnawake leave school with a much different identity than she did.

"Children leave school knowing exactly what they're all about," she said.

"It was fantastic to be a part of that. What's wonderful is that when these Kahnawake students leave and go off to universities, they take that pride with them, and they're not shy at all of sharing it, which is something that I never did."