MONTREAL -- With pandemic restrictions lifting and offices getting set to decide how they will operate after over a year of remote work and other non-traditional work settings, many are asking if it's time to reconsider the five-day workweek.

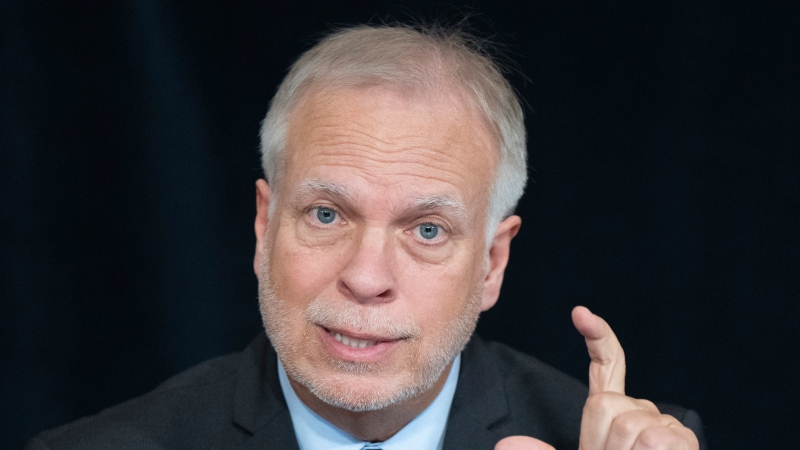

McGill University organizational behaviour professor Jean-Nicolas Reyt said CEOs are already speaking about hybrid work models with home and office time split, which would save massive amounts of money in real estate investment.

The next matter worth considering, he said, is giving employees an extra day off.

"This is a lot of savings," said Reyt. "So already you have that part, where if you could have people work four days a week instead of five days a week."

The David Suzuki Foundation implemented the four-day workweek in the early 2000s.

"It's worked out awesome," said director of innovation for Ontario and the North Yannick Beaudoin. "This is what it should be by now and I'm surprised we're not getting more attention and media requests on it by now."

Beaudoin said switching the schedule helped the company look more at the quality of productivity rather than the quantity.

"It does two things," he said. "They're still able to show that highly energized, work-life balance people will be quantitative as or more productive."

In addition, Beaudoin said it helps companies and organizations redefine what performance is.

"The foundation is much more inclined to look at the qualitative aspect of performance, so the quality of someone's work," said Beaudoin. "Now we are much more actively monitoring that aspect of people and their work rather than how many sprockets they make in a day."

The pandemic has altered perceptions of how, where and when to work, and Reyt said keeping an eagle eye on employees working from home is counterproductive.

"The pandemic has dissociated work from place and time," he said. "If you have all of the employees working from home, it's kind of like useless to try to track the time too much, or try to see if they're behind their computers and you hear clicks and things like that. All of these were like very poor indicators of performance and so I think a lot of companies just started to look at actual performance, not, how is the person showing up or are they late, which nobody cares about."

A study of Iceland's four-day workweek between 2015 and 2019 followed 2,500 workers and showed an improvement in the quality of work-life balance and did not show a drastic decline in productivity.

"The trials were an overwhelming success, and since completion, 86 per cent of the country's workforce are now working shorter hours or gaining the right to shorten their hours," reads a summary of the study by Autonomy - a U.K.-based research firm.

Microsoft Japan went to a four-day workweek in 2019 and saw productivity rise by 40 per cent. Employees in the study took 25 per cent fewer days off during the month.

Reyt does not see a four-day week as a catch-all, but it is something to consider.

"It doesn't work for everyone, I think. You know, some people want it, some people don't want it. I think what's important is to have more flexibility and work arrangements."

Reyt said that while productivity has increased in the last half-century, the office employee can rarely support a family with only one salary, as they may have been able to five decades ago.

"It's an interesting question... Where is all of this productivity going? Because it's definitely not going into employees working less and it's not going into employees making more," he said.

The five-day workweek was something conceived in the early 20th century in an industrial setting, and people like Beaudoin and Reyt see the concept as something needing to updated at least to the 21st century.

"It comes from a time when we literally called it human resources; it wasn't humans, it wasn't people, it was labour and resources," said Beaudoin. "Who does that really serve?"