Sexting is a 'constant problem' in Quebec schools: experts

With Quebec high school and elementary students potentially stuck at home due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the temptation to spend time online could increase.

On one hand, it could be a way for kids to stay connected to their friends and feel less isolated.

However, there isn't a guarantee that what they're talking about is completely healthy and harmless.

Every year, school authorities receive numerous reports of sexting incidents that put students in dangerous situations.

Oftentimes, it involves one student asking a classmate for an intimate photo or video and then sharing those private images to others -- or a child sending someone unsolicited sexual photos of themselves.

This “problematic sexual behaviour” is not limited to high school students, stressed an English Montreal School Board (EMSB) psychologist in an interview with CTV News.

“It does occur in elementary school. Probably not as often as in high school, but every year I have to do some sort of intervention,” said Lena Celine Moise, who works with students in Grades 1 to 6.

The idea that young kids could engage in that kind of behaviour or be victimized by a student of the same age can be hard for parents to grasp, she adds.

“They will say, 'oh, dear, sweet, young, innocent ones don't think about these things at those ages,'” Moise said. “Mentally, they're much more precocious than we were at their age, I think because they're exposed to so much more and more is accessible."

Easy access to sexually provocative content on websites and gaming platforms, combined with the early stages of puberty, can blur the lines between what is and isn’t appropriate in the real world.

“Romantic attraction, feelings for somebody else and their sexual impulses,” are starting to burgeon, explained Moise, but “they kind of don't know how to use them appropriately.”

A LEARNED BEHAVIOUR

Moise shares a situation she helped handle that involved a child in Grade 4 who was “preyed upon” by an adult, like “a lot of kids” who are online.

This nine-year-old boy's “first exposure to sexting had to do with some people on the internet asking him to reveal his private parts,” she said.

When the child's parents heard what had happened, they took immediate action and explained to their son why it was inappropriate, Moise adds.

They also confiscated his phone and monitored his social media for incoming messages.

“They did intervene with him,” she said, adding a couple of years later, when he was in Grade 6, the boy asked some girls to do the same thing. "He asked them to show [intimate] pictures of themselves.”

The girls didn’t comply, but Moise says the inappropriate sexual request caused a lot of discomfort and confusion.

“Because this is a classmate, I like this person as a friend, and I'm going to hurt their feelings,” Moise said.

After some modelling of appropriate behaviour and lots of discussions, the young students at the Montreal school learned how to be assertive and set boundaries.

Regardless, if there is no support or reeducation, “a lot of those behaviours become normalized,” Moise said, explaining sometimes younger kids think that everything they see online is “real life” and therefore, “anything goes.”

Sometimes, school experts do call in authorities from the province’s youth protection system to consult.

“We want to make sure the child is not engaging or wanting to engage in such sexual behaviour because he's been victimized in the home or he’s not properly supervised,” Moise noted.

SEXTING AND CONSEQUENCES

The fact that sexting is an ongoing issue among high school students doesn’t surprise sexologist Myriam Le Blanc Elie, but she says it is “preoccupying.”

A study she conducted in 2018 for Fondation Marie-Vincent (FMV) underscores how common it is, she said.

The organization supports children who are victims of sexual and physical violence.

“We noticed that 36 per cent of girls and 16 per cent of boys already received an intimate photo from someone, or were sent a photo or were asked for an intimate photo,” Le Blanc Elie said. “That really hit us. Thirty-six per cent, that’s more than one girl out of three.”

She adds there are “big consequences for the victims and big legal consequences in certain cases,” for teenaged perpetrators.

Nevertheless, no matter how many times that message is repeated, Le Blanc Elie says it just “doesn’t get through” to all the kids.

Five Montreal high schools participated in the research project in the hopes of getting a better sense of student needs in order to create a new cyber-violence prevention program.

About 850 students answered survey questions about time spent online, which applications they use, parental supervision, rules at home and experiences with online victimization.

“We try to identify novel solutions,” said Le Blanc Elie. "It’s hard sometimes to be empathetic when you’re in front of a computer screen... [and] young people reflect society in how we treat men and women, with regard to sexuality.”

She notes schools play an important role in teaching prevention and sex education.

“Parents need to play a significant role in the life of their kids,” the sexologist said, adding it's important to talk about sexting “so it’s not a taboo and not something we only talk about when it’s too late.”

RETALIATORY SEXTING

One of the more common forms of sexting aggression can occur after a high school break-up, Le Blanc Elie notes.

“Kids have already spoken to me about keeping a collection of photos they received [from their romantic partner] just in case -- if one day the other person makes me angry or bugs me I can always send the photos to other people,” she said.

She gives the example of one young high school girl who met an older boy online.

As they chatted they exchanged intimate photos.

The older boy, who attended a different high school, apparently threatened that if she didn’t continue to send him photos he would send the ones he already had to all her friends on social media.

She refused and he followed up with his threat, sending the images to a large group of people.

The aftermath, Le Blanc Elie explains, was devastating for the girl.

“You have a student who doesn’t want to go to class because she feels everyone is staring at her, she can be intimidated in the hallway, and this is just one case,” she said.

PROJECT SEXTO

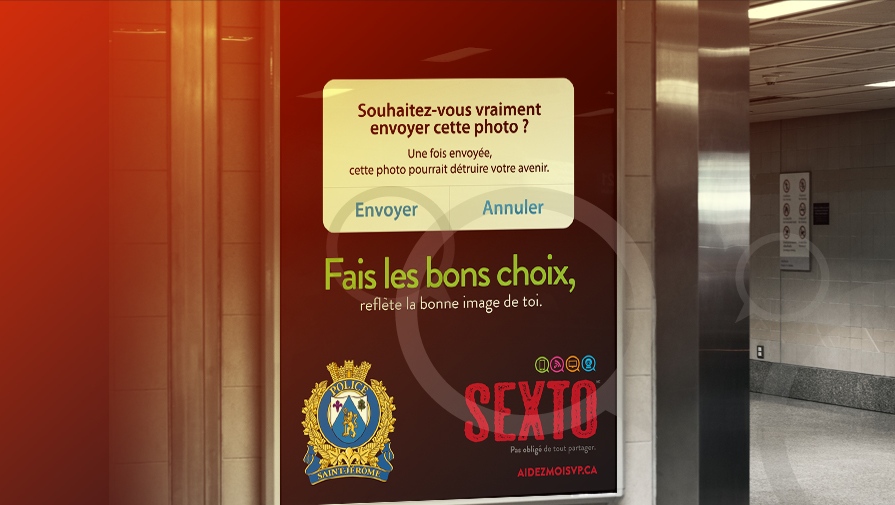

Along with the prevention and support programs offered to schools by FMV, Quebec is combatting sexting through an initiative called Project Sexto, launched in Saint-Jérôme in 2016.

A Crown prosecutor who works with youth offenders in the small Laurentian city says not only does the project get results, but partners all over Quebec work quickly when a case is brought to their attention.

“With the ‘sexto’ method, there is an average delay of four days for the intervention,” Aubree Coutanson told CTV News. “It’s very fast, which is good because we know the images can be shared quickly and the situation can degenerate.”

The humiliation that can follow after nude photos are leaked can lead victims to drop out of school, develop depression or even suicidal ideation, according to the program’s website.

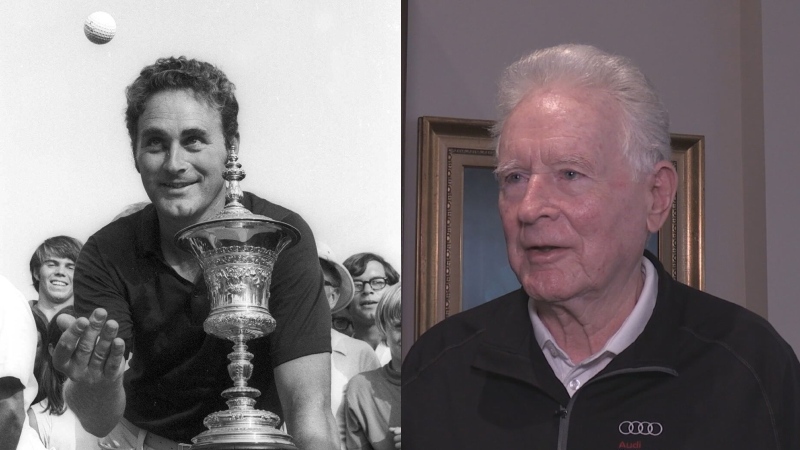

Police, prosecutors and school staff are launching Project SEXTO province-wide to draw attention to the phenomenon of sexting among youth. SOURCE: SQ

Police, prosecutors and school staff are launching Project SEXTO province-wide to draw attention to the phenomenon of sexting among youth. SOURCE: SQ

Project Sexto brings together Crown prosecutors, schools and nearly two dozen participating police forces.

It currently operates in 21 jurisdictions, including Laval, Longueuil, Deux-Montagnes and Sherbrooke, but it is not yet available in Montreal.

“We are deploying it around the province,” Coutanson told CTV News. The Montreal version is “in progress,” she notes, adding discussions are ongoing, but there’s no fixed start date.

HOW PROJECT SEXTO WORKS

Anyone implicated in a harmful sexting incident can get help from a person in authority at their high school wherever Project Sexto is being used.

When a victim tells a teacher they “shared some images and now they’ve lost control of them,” for example, the program is set in motion.

The school fills out a prepared evaluation grid designed to elicit as much detail as possible about what occurred.

School officials then send the evaluation form to the Crown prosecutor’s office.

The offending images or videos are not forwarded, but a description is included in the report.

Based on the information provided, prosecutors decide whether the act of transmitting the images to others was an impulsive act or if it was maliciously motivated.

If it is declared impulsive, police officers are sent to the school to hold a sensitization session with the student who shared the images.

Officers also do what they can to ensure the media is deleted.

“We know that youth are immature…they will act with their impulses. They want to please, sometimes they are pressured,” Coutanson said. “[Under] the Criminal Code, a charge of juvenile pornography can also apply to 12-17-year-olds,” said Coutanson.

She says the perpetrator “could be accused” if ever they do it again and the images are determined to be a form of juvenile pornography.

If the sexting was done with malicious intent, prosecutors will ask for a criminal investigation.

“That doesn’t mean that necessarily it will end up in the justice system, but the case will be investigated,” Coutanson said.

Out of 422 sexting files that came to Project Sexto from Quebec high schools before July 2021, almost 70 per cent led to sensitization sessions, and 30 per cent were criminally investigated.

“Education is a better way to prevent recidivism,” Coutanson said, noting only 1.2 per cent of those who received sensitivity and awareness training, repeated the behaviour.

Sexting is “a constant problem, but we saw that youth react positively to Project Sexto,” she said.

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

DEVELOPING Man sets self on fire outside New York court where Trump trial underway

A man set himself on fire on Friday outside the New York courthouse where Donald Trump's historic hush-money trial was taking place as jury selection wrapped up, but officials said he did not appear to have been targeting Trump.

BREAKING Sask. father found guilty of withholding daughter to prevent her from getting COVID-19 vaccine

Michael Gordon Jackson, a Saskatchewan man accused of abducting his daughter to prevent her from getting a COVID-19 vaccine, has been found guilty for contravention of a custody order.

She set out to find a husband in a year. Then she matched with a guy on a dating app on the other side of the world

Scottish comedian Samantha Hannah was working on a comedy show about finding a husband when Toby Hunter came into her life. What happened next surprised them both.

Mandisa, Grammy award-winning 'American Idol' alum, dead at 47

Soulful gospel artist Mandisa, a Grammy-winning singer who got her start as a contestant on 'American Idol' in 2006, has died, according to a statement on her verified social media. She was 47.

'It could be catastrophic': Woman says natural supplement contained hidden painkiller drug

A Manitoba woman thought she found a miracle natural supplement, but said a hidden ingredient wreaked havoc on her health.

Young people 'tortured' if stolen vehicle operations fail, Montreal police tell MPs

One day after a Montreal police officer fired gunshots at a suspect in a stolen vehicle, senior officers were telling parliamentarians that organized crime groups are recruiting people as young as 15 in the city to steal cars so that they can be shipped overseas.

The Body Shop Canada explores sale as demand outpaces inventory: court filing

The Body Shop Canada is exploring a sale as it struggles to get its hands on enough inventory to keep up with "robust" sales after announcing it would file for creditor protection and close 33 stores.

Vicious attack on a dog ends with charges for northern Ont. suspect

Police in Sault Ste. Marie charged a 22-year-old man with animal cruelty following an attack on a dog Thursday morning.

On federal budget, Macklem says 'fiscal track has not changed significantly'

Bank of Canada governor Tiff Macklem says Canada's fiscal position has 'not changed significantly' following the release of the federal government's budget.