The Quebec government has released a plan to build thousands of new seniors’ units across the province, but part of that plan includes putting cameras in each room – something that’s drawn controversy as some raise privacy and staffing concerns.

The province says the cameras will help staff monitor residents, especially those with dementia who may wander out of their living spaces.

"The cameras also allow for an in-depth analysis of the causes and consequences of certain events, such as a fall," wrote Noémie Vanheuverzwijn, a spokesperson for the health ministry, in a statement to CTV News.

Paul Arbec, presidents of Groupe Santé Arbec, which represents private long-term care homes, says surveillance can protect the elderly.

“I think it's an excellent tool, a clinical tool and a human resources tool,” he said. “When we have to do our inquiries into situations that may or may not have been abuse or mistreatment, it's a lot easier when we've got it on film.”

However, when it comes to the government's surveillance, Arbec has concerns about privacy and protecting the dignity of residents, and so does the union representing health-care workers.

“We don't know where this falls legally,” said FIQ president Julie Bouchard, “for employees or residents.”

It's been legal in Quebec for families to install their own cameras in rooms since 2018, with certain conditions.

The government says cameras will only be turned on with the permission of residents or their legal representatives.

"In seniors' homes, technology will make it possible to better meet the needs of residents, including the possibility of having acoustic, visual or motion detection surveillance in the rooms of residents whose condition requires it and who request it," wrote Vanheuverzwijn.

"In no case shall a surveillance mechanism be used automatically in a user's room, but rather be the subject of a clinical objective provided for in the resident's intervention plan," she continued.

But patients’ rights advocates say cameras don't work if nobody is watching.

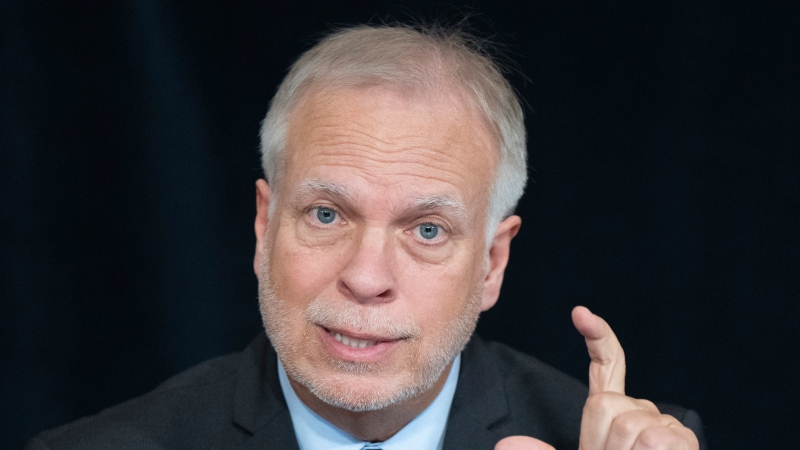

“Do we have sufficient personnel to on 24 hours a day to make the appropriate surveillance of what the camera is going to show?” asked Paul Brunet, CEO of the Council for the protection of patients.

“We're already lacking personnel to make decent food, for decent hygene,” he said.

The union also raised concerns that the surveillance tool could mean fewer jobs.

"We work with human beings," said Bouchard. "We need to check on people in person."

"This is absolutely not a tool to compensate for the lack of personnel," wrote the ministry spokesperson.

"The use of the camera must only serve as a clinical means to analyze a situation and to plan the intervention accordingly or to better respond to the needs of the residents."