QUEBEC CITY -- The Legault government has still not tabled a bill to extend medical aid in dying (MAID) to people suffering from Alzheimer's disease, almost four months after receiving the report it was waiting for.

On Dec. 8, a special commission recommended that anyone diagnosed with a serious and incurable illness leading to incapacity should be able to sign an advance application for MAID.

This excludes people whose only medical problem is a neurological disorder.

On Monday, with time running out and the election deadline looming, MNAs on the committee worked together to call on the government to make its intentions known.

They argued that there is a segment of the population that is looking forward to this bill.

"If your mother learns today that she has Alzheimer's and that she is already at stage 3, (...) she cannot apply for medical aid in dying," Vincent Marissal of Québec solidaire said in an interview.

"I don't want to scare the world, but (...) if we are not able to adopt the bill this session, well, in my opinion, we'll start again and we'll have a year's worth of work ahead of us," he summarized.

Recall that the current law, passed in 2014, sets very strict criteria to be able to claim from a doctor to end their life.

The patient's informed consent, up to the point of death, is central to the process, with some exceptions. People diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease do not have access to it under any circumstances.

According to the members of the commission, their position reflects "the major trends" in opinion seen in Quebec society on this subject in recent years.

There is now, they say, a "social consensus" in favour of extending the law to persons who have become incapacitated.

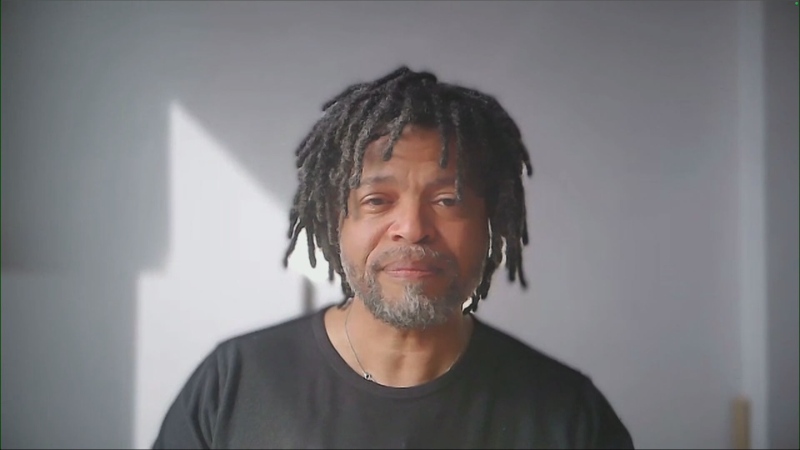

"If I become incontinent, unable to identify my children, (...) in a very clear way, I will be able to know that my life will be able to end in dignity," said Liberal MNA David Birnbaum.

"That's what's at stake, so let's go," he added in an interview.

The National Assembly has only about 30 sittings left, which is not very many considering that any potential bill will have to be studied in detail.

Moreover, there are already three bills pending in the Health and Social Services Committee, which is currently studying Bill 15 on youth protection.

"It's unfortunate, because if (the MA) had been prioritized when we came back in February, (the bill) would already be passed," said Marissal, who criticizes the government for its "mismanagement of the legislative process.

STILL POSSIBLE?

Despite this, PQ MNA Véronique Hivon, a former member of the commission and considered the 'mother' of the current law, believes that the bill can still move forward.

According to her analysis, a minister other than Health Minister Christian Dubé could table the bill on MAID, and entrust its study to the institutions commission, for example.

"There is nothing impossible," she said in an interview, before adding: "I don't see how the government could ignore such a thorough work that has been done, which carries such a large consensus of the population."

In their report, the members of the special commission said the role of physicians would be a deciding factor in ensuring the proper management of directives for the future.

The attending physician should ensure that the request is free and informed. He or she should also ensure that the patient understands the nature of the diagnosis and the expected course of the illness.

The applicant could even write on the form the stage of the disease at which he or she wishes to receive treatment to end their life.

He or she should identify a "trusted third party" who would be responsible for alerting the medical authorities when he or she feels that the time has come to act on his or her wishes.

This person would be responsible for "waving the flag," according to Hivon, who reminded us that Quebec is "a forerunner" in this area of end-of-life care.

According to the commission's wishes, the form should be signed in the presence of two witnesses and a physician, and the procedure could in future be administered by either a physician or a specialized nurse practitioner (NP).

It would be up to the medical authorities to decide whether the request met the criteria and when to proceed.

A seven-day consultation on this sensitive topic was conducted last spring and August. A total of 77 individuals and organizations were heard and 75 briefs were submitted.

- This report by The Canadian Press was first published in French on March 21, 2022