MONTREAL -- New findings out of McGill University in Montreal have revealed a potential way to overcome aggressive brain tumours' resistance to therapy: by deleting a specific gene.

Researchers have long been searching for ways to treat Glioblastomas – the most stubborn type of brain tumour – as they’re well known for their resistance to treatment.

A few years back, they were able to confirm the key role a gene called the OSMR gene plays in the process of brain cancer growth. By deleting this gene in mice with tumours created from human patient cells, researchers at McGill were able to extend the critter’s life expectancy post-treatment by more than 50 per cent.

“We previously showed (the OSMR) gene regulates tumour growth,” said Dr. Arezu Jahani-Asl, assistant professor of medicine at McGill University whose lab oversaw the study, published in Nature Communications on Monday. “They produce more energy so the cancer cells can use this energy to survive."

The current process to fight Glioblastomas is to remove them surgically, then perform radiation and chemotherapy on the patient.

“Despite intense efforts, the patients die on average between 16 to 18 months" after diagnosis, Jahani-Asl said. “They always come back, these tumours, and it’s just impossible to get rid of them.”

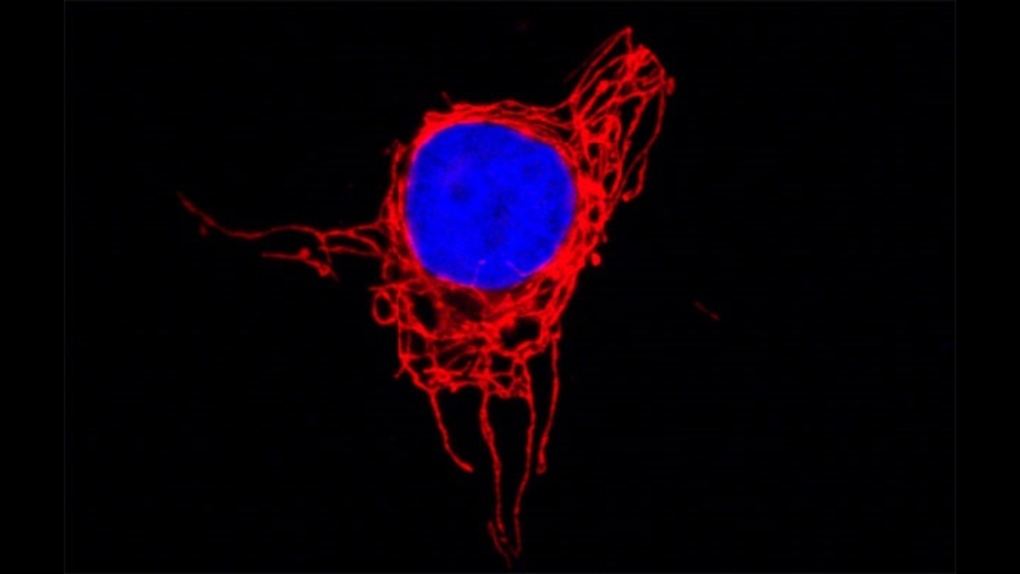

Glioblastomas are composed of several types of cells, including brain tumour stem cells, Jahani-Asl explained. These cells can divide to give rise to new tumours but at the same time can remain dormant – meaning they don’t divide – which makes it impossible to target them because therapeutic treatments are specifically designed to target dividing cells.

“It’s like sleeping; the stem cells go to sleep and then they can’t be targeted,” Jahani-Asl said. “They evade ionizing radiation and chemotherapy.”

So despite surgeries and treatments, the cancer cell can wake up -- or exit dormancy -- and grow back because it’s impossible to get rid of all the cells.

But when the OSMR gene is removed, "the cells don’t produce as much energy, and they respond better to (treatment),” Jahani-Asl said, adding that genes can be deleting using a technology called CRISPR.

While results in mice have been promising thus far, it takes time to transfer these types of discoveries to human patients, Jahani-Asl said. The next step will be to use these tools in a clinical trial.

Jahani-Asl has been working on the OSMR gene for upwards of 10 years, and this particular study for around five.

“We’re hoping we can put these little pieces together for something good to come out of it,” she said.