Mayoral candidates promise to make Montreal safer — but will their proposals work?

At the opening of the English-language mayoral debate last Thursday, Onica John asked the top three contenders for mayor of Montreal what they promised they would do to make the city safer for youth.

Just 10 days before the debate, John’s 16-year-old cousin, Jannai Dopwell-Bailey, had been fatally stabbed in the parking lot outside his school in the Cote-des-Neiges neighbourhood. Another 16-year-old boy was charged with second-degree murder in the teen’s Oct. 18 killing in broad daylight, which was the city's 25th homicide of the year and one of five killings in Montreal in the month of October alone.

“What are you going to do about safety at school for our children since this incident?” the grieving woman asked Projet Montreal leader, incumbent mayor Valerie Plante, and candidates Denis Coderre and Balarama Holness.

- Watch the full-length Montreal English mayoral debate

- Montreal mayoral debate centres on crime, climate change, and housing

Plante committed to getting guns off the street, dismantling organized crime and enhancing community relations in a three-pronged approach to enhance public safety.

Coderre, leader of the Ensemble Montreal party, answered the question by saying he would hire 250 more police officers and coordinate a “pan-Canadian” network to establish best practices to tackle the root causes of crime. Coderre has also previously pledged to equip officers with body cameras — a commitment he said would be implemented in the first 100 days of his mandate.

Meanwhile, Holness, the Mouvement Montreal leader, said youth are missing the opportunities “to flourish in society” and offered a “new approach” to invest in more social services and less in policing budgets and to support underfunded communities.

Police officers investigate a crime scene following a shooting leaving three people dead and two injured in residential neighbourhood of Montreal on Tuesday, August 3, 2021. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Paul Chiasson

Police officers investigate a crime scene following a shooting leaving three people dead and two injured in residential neighbourhood of Montreal on Tuesday, August 3, 2021. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Paul Chiasson

Police officers investigate a crime scene following a shooting leaving three people dead and two injured in residential neighbourhood of Montreal on Tuesday, August 3, 2021. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Paul Chiasson

Three different answers to the same question gave voters a glimpse into the priorities of the major parties heading into the Nov. 7 municipal election when it comes to public safety.

What’s different this year is that Montrealers have a leading candidate who, for the first time, has pledged to defund the Service de police de la Ville de Montréal (SPVM).

WHY SHOULD VOTERS CARE?

This is significant for many reasons, but one is that the key to defunding the police is shifting taxpayer dollars. The largest portion of the city’s $6 billion budget for 2021 was dedicated to public security — policing and fire services. Just over $679 million went to the SPVM alone.

Last November, a coalition of people representing 57 community organizations stormed City Hall during the 2021 budget presentation to voice their opposition to the sizable chunk of money for the SPVM’s total budget.

Their demand: cut the police budget in half — which would be about $340 million — and to reinvest the rest in community services in areas like homelesses, mental health, and gender-based violence.

Advocates of defunding the police argue that armed police officers shouldn’t be the ones responding to all 911 calls, especially ones that have no criminal element or that can be better addressed by social services. For example, a person with mental health issues who is in distress or assisting someone with an addiction.

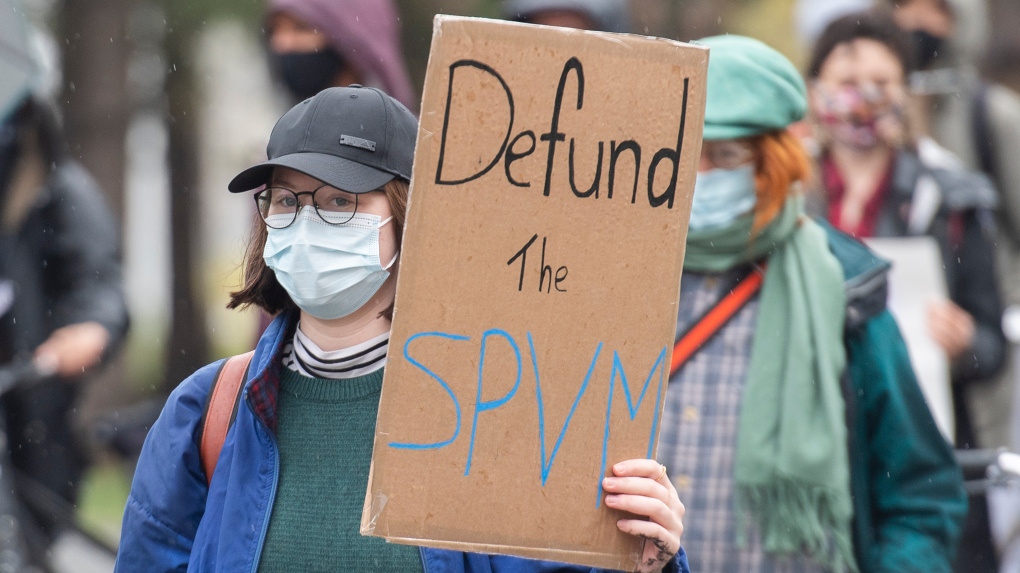

People take part in a demonstration against police brutality in Montreal, Sunday, April 25, 2021. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Graham Hughes

People take part in a demonstration against police brutality in Montreal, Sunday, April 25, 2021. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Graham Hughes

People take part in a demonstration against police brutality in Montreal, Sunday, April 25, 2021. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Graham Hughes

Holness, leader of the Mouvement Montreal party, is proposing the closest thing to what those protesters were calling for last fall. He has pledged to cut $100 million of the $550 million that goes into the police officers’ salaries and reinvest it in social services.

POLICE OFFICERS SHOULDN'T RESPOND TO EVERY 911 CALL: CONCORDIA PROFESSOR

Ted Rutland, a Concordia University professor whose research focuses on policing in Canada, has been a vocal advocate for defunding the police and “civilian intervention teams” because it “ensures that you actually have the best people sent to deal with the problems at hand.”

“We see cities moving towards this across North America, including Toronto, but the primary, historical examples are Eugene, Oregon. And I think that it's great to see these ideas for the first time and in this local election campaign,” he said. “I think that if Montreal takes time to learn about these examples, they'll see that these are really important things.”

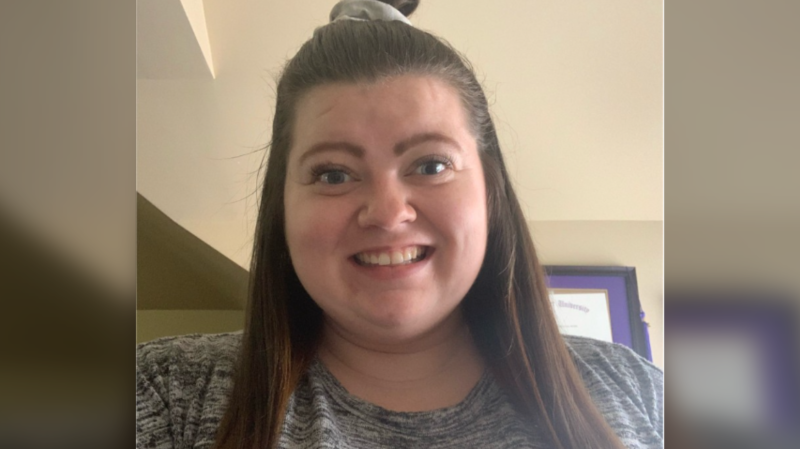

Ted Rutland, a Concordia University professor, says a hiring freeze in the SPVM would be the easiest way the City of Montreal could reallocate policing funds to social services. (Joe Lofaro/CTV News)

Ted Rutland, a Concordia University professor, says a hiring freeze in the SPVM would be the easiest way the City of Montreal could reallocate policing funds to social services. (Joe Lofaro/CTV News)

Ted Rutland, a Concordia University professor, says a hiring freeze in the SPVM would be the easiest way the City of Montreal could reallocate policing funds to social services. (Joe Lofaro/CTV News)

The small town of Eugene is often used as an example of how the defunding police approach can work. A mobile response team comprising a medic and a crisis worker has been established since the late 1980s and has helped save the Oregon town about $8.5 million in annual public safety funding. Of the roughly 24,000 calls it responded to in 2019, about 150 of them reportedly required a police response.

One of the easiest ways to reallocate funds from the police budget, Rutland said, is for the city to issue a hiring freeze for Montreal police to avoid replacing officers who retire or leave the force.

“We've seen hiring freezes as a way of ensuring proper allocation of public resources in the past, but we haven't applied that to the police yet, which sort of means that we've seen the police budget increase consistently,” he said.

“Whereas budgets in other departments can go up at times when it's a priority and can decline at other times when we're de-prioritizing them.”

'IT PROBABLY WON’T WORK’

However, not everyone who studies policing practices is convinced defunding is the best solution to making cities safer. Rémi Boivin, a criminology professor at the Université de Montréal who also spent almost five years as a crime analyst at the SPVM, said there is a lack of empirical studies to show it would work here.

He doesn’t believe defunding the Montreal police service is a “feasible” alternative, at least in the short-term.

“It probably won’t work,” Boivin told CTV News.

“In the U.S. yes [some cities have tried it], but it's always in the context of, for example, a federal investigation or major problems often related to the use of force. The American context and the Canadian or Quebec context are so different that it's difficult to translate the American literature to the Canadian context.”

Rémi Boivin, a criminology professor at the Université de Montréal, believes it's not 'feasible' to defund the Montreal police as a short-term solution. (Joe Lofaro/CTV News)

Rémi Boivin, a criminology professor at the Université de Montréal, believes it's not 'feasible' to defund the Montreal police as a short-term solution. (Joe Lofaro/CTV News)

Rémi Boivin, a criminology professor at the Université de Montréal, believes it's not 'feasible' to defund the Montreal police as a short-term solution. (Joe Lofaro/CTV News)

Police organizations in U.S. cities are more independent than in Quebec or elsewhere in Canada where the political structures are more centralized, he said.

Hotspot patrolling — whereby police officers focus their resources in areas with the most concentrations of crime — has proven to be more effective at reducing crime, according to Boivin.

“I would say [to] defund the police to have an immediate impact would not have the effect that we want, which is crime [decreasing], crime prevention, and the development of community interventions,” he said.

“I think in the longer term, it would be a very good idea to actually change the trend, which is to increase police budgets. It would be a good idea in the longer term to actually decrease the budget but not necessarily to put on a drastic measure.”

CRIME IS GOING DOWN IN MONTREAL

One argument to be made for de-prioritizing police budgets is that overall crime in Montreal, like other cities, has been trending downward over the last several years. The number of criminal code violations in 2015 was 101,976, which is far higher than the 87,842 violations there were in 2020, according to SPVM annual reports. The crime variation rate for Montreal in 2020 was also 11 per cent lower than the rate in 2019.

Still, those numbers might not be enough to convince voters when they see reports of shootings and killings on the streets of Montreal this year, particularly this summer.

In fact, there have been 28 homicides so far in 2021 — a number Montrealers haven’t seen this high since 2018, when there were 32.

There are also a concerning number of femicides in Montreal and elsewhere in Quebec this year — an issue the provincial government has promised to address with funding for things like women’s shelters and dedicated police units for domestic violence.

Quebec’s public safety minister noted armed offences have more than doubled in Montreal from 2019 to 2020 when she announced $5 million in the summer for Montreal’s anti-gun squad, the équipe dédiée à la lutte contre le trafic d’armes (ELTA), which was created in January to stem the flow of illegal guns into the city.

Montreal has already surpassed the number of gun-related crimes there were in 2020, according to data provided to CTV News by the SPVM. By the end of August, there were 39 crimes involving a firearm. By this time in 2020, there were 38, and 33 in 2019.

The data covers all types of crimes in which a firearm was present, whether real or fake and whether it was used or not.

PLANTE, CODERRE PROMISE 250 NEW POLICE OFFICERS

Plante and Coderre have both said in the election campaign they would not cut police funding. Instead, Plante has pledged to support the fight against organized crime by permanently funding the ELTA team to tackle Montreal's gun problem.

She also promised to invest $5 million annually for community organizations that work in crime prevention among youth and to create a “mobile mediation and social intervention team” to assist marginalized people who are in crisis or distress.

Montreal Mayor Valerie Plante and Police Chief Sylvain Caron listen to a question a news conference in Montreal on Thursday, February 11, 2021. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Paul Chiasson

Montreal Mayor Valerie Plante and Police Chief Sylvain Caron listen to a question a news conference in Montreal on Thursday, February 11, 2021. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Paul Chiasson

Montreal Mayor Valerie Plante and Police Chief Sylvain Caron listen to a question a news conference in Montreal on Thursday, February 11, 2021. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Paul Chiasson

Another thing Plante and Coderre have in common — they both are promising body cameras for Montreal police officers in 2022 and, just on Tuesday, the Projet Montreal leader announced she, too, would hire 250 more police officers.

In contrast to Holness, Coderre’s Ensemble Montreal party has promised to not only hire more officers but also to ask the province to increase the police cap of 4,802 officers authorized by Quebec’s public safety ministry to 5,000 officers “if the need arises.” There were 4,496 sworn SPVM officers as of Oct. 15, 2021. Over the last few years, the workforce peaked in 2017 with 4,591 officers.

“More hires and retirements are expected before the end of the year,” the SPVM told CTV News.

Coderre, who was mayor of Montreal from 2013 to 2017, also wants to double the number of police officers in the SPVM psychosocial emergency support team (ESUP) and the Homelessnes Referral and Intervention Team (EMRII) at an estimated $10 million, “in order to ensure proper follow-up with hospitals and social workers and to divert homeless cases from the judicial process.”

Holness’ other campaign promises for public safety include mandating specialized police training for domestic violence incidents and yearly cultural sensitivity and anti-racism training. If elected, he said he would also create a special emergency phone line for intervention workers, social workers, and mental health professionals trained in de-escalation, domestic violence intervention, and substance abuse.

Whatever approach the city takes after the election, Boivin said he believes that Montreal is still a safe city overall.

“For sure, there's an increase [in gun crime] and so on,” he said, “but if we compare to other big cities in the world, Montreal is a very safe city.”

The municipal election takes place Nov. 7.

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Trump is open to using 'economic force' to acquire Canada; Trudeau responds

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said 'there isn’t a snowball’s chance in hell that Canada would become part of the United States,' on the same day U.S. president-elect Donald Trump declared that he’s open to using 'economic force' to acquire Canada.

Los Angeles residents flee wildfire as fierce winds gain strength

Firefighters scrambled to corral a fast-moving wildfire in the Los Angeles hillsides dotted with celebrity homes as a potentially 'life-threatening, destructive' windstorm hit Southern California on Tuesday, fanning the blaze seen for miles while roads were clogged with cars as residents tried to flee.

Patient dies in waiting room at Winnipeg hospital

An investigation is underway after a patient waiting for care died in the waiting room at a Winnipeg hospital Tuesday morning.

Canada has a navy ship near China. Here's what it's like on board

CTV National News is on board the HMCS Ottawa, embedded with Canadian Navy personnel and currently documenting their work in the East China Sea – a region where China is increasingly flexing its maritime muscle. This is the first of a series of dispatches from the ship.

New Westminster police incident that triggered evacuations of courthouse, college has cleared

A threat against the courthouse in New Westminster triggered evacuations in the city’s downtown Tuesday morning, according to authorities.

B.C. 'childbirth activist' charged with manslaughter after newborn's death

A British Columbia woman who was under investigation for offering unauthorized midwifery services is now charged with manslaughter following the death of a newborn baby early last year.

Man who exploded Tesla Cybertruck outside Trump hotel in Las Vegas used generative AI, police say

The highly decorated soldier who exploded a Tesla Cybertruck outside the Trump hotel in Las Vegas used generative AI including ChatGPT to help plan the attack, Las Vegas police said Tuesday.

David Eby among premiers heading to Washington to tamp down Trump tariff threat

The 'state of the federal government' following the announcement that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau would resign means Canada's premiers are taking the lead in the fight against threatened tariffs from U.S. president-elect Donald Trump, British Columbia Premier David Eby said.

Trump refuses to rule out use of military force to take control of Greenland and the Panama Canal

U.S. president-elect Donald Trump on Tuesday said he would not rule out the use of military force to seize control of the Panama Canal and Greenland, as he declared U.S. control of both to be vital to American national security.