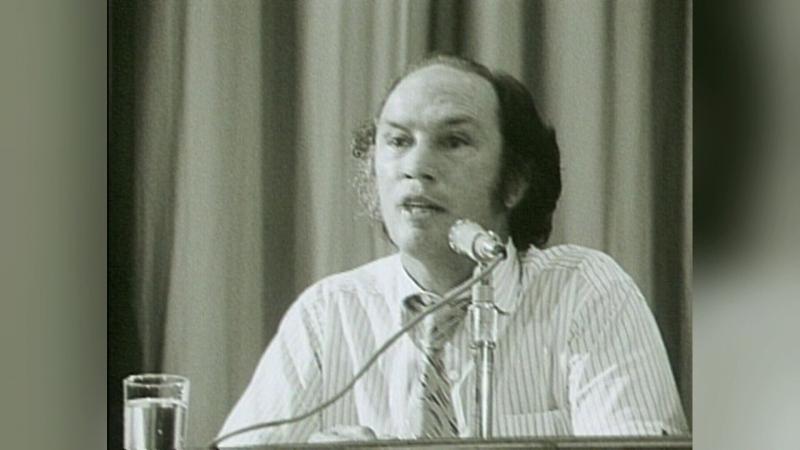

MONTREAL—On Monday afternoon, Jacques Duchesneau wore the calm mask available only to a man who had been in the public spotlight for the past year.

Fielding questions from journalists since 6:00 a.m., the newly minted star candidate for the Coalition Avenir Quebec had already made his first major gaffe as a politician, received a public reprimand from his leader and was making his third very public correction.

All within his first day on the campaign trail.

“I’m not a politician,” dropped Duchesneau in a half-whisper, leaning forward in his chair as though he was sharing a secret. “That’s the problem.”

It was hardly a secret. Lovingly described by struggling CAQ leader Francois Legault as the “everyman candidate,” the entire province of Quebec is keenly aware of Montreal’s former chief of police, whose tendency to charge into problems like a bull moose has earned him an Order of Canada ribbon.

For the past two years, Duchesneau’s name has been intertwined with Quebec’s fight to control corruption. Captivating audiences with his straight-talking testimony at the Charbonneau Commission over the summer, Duchesneau described a system of systematic corruption that shook the foundation of the province’s political order.

While describing a Liberal government throwing obstacles at his inspectors on a near daily basis, Duchesneau named names and spoke about a system of kickbacks far more complex and deeply-rooted than any of Quebec’s recognizable figures were willing to admit.

After an early-morning interview with 98.5 FM, Duchesneau fidgeted in his chair at CTV’s Montreal office. Admitting mistakes doesn't come easy to Duchesneau.

“I tried to make a short story too short this morning,” explained Duchesneau, as he started to backtrack. “Obviously the sole responsibility for nominating cabinet ministers falls on the premier.”

Slated to become the deputy premier of Quebec—if only the Coalition can convince Quebecers to put the untested party in power, an extreme long shot six days into the campaign—Duchesneau’s reveal as a candidate had sent Quebec’s two major parties scurrying.

After a nasty public fight with Premier Jean Charest over how hard the Liberals had combated corruption—Charest gave himself an eight on ten, Duchesneau a significantly more modest two on ten—the new caquiste lieutenant had given his opponents ammunition to fight back on Monday morning.

Duchesneau plainly told a radio host on Monday that if elected, he would have the power to appoint at least four cabinet ministers within Francois Legault’s government. Those ministers, responsible for transportation, public safety, natural resources and municipalities, would report to him as he rid the province of corruption.

“I goofed. It’s quite clear that the premier makes those nominations, there is only one chief,” the former top cop said, hours after his gaffe.

“What I tried to say this morning is that I decided to join the CAQ and go into politics because I would be focusing on the anti-corruption law that we would like to put in as law number one,” said the former investigator. “My main responsibility would be tackling that problem.”

While Legault charged that Jean Charest has run a government of post-it-notes, with all the problems of the sticky pieces of paper, he said that he was willing to step back as anti-corruption czar and whisper cues to the quite unlikely Premier Legault. He went as far as to say that he would be “very comfortable” as a corruption consultation in the government, mumbling agreement to the question.

“Legault talks, that’s the main difference,” he said. “With Jean Charest, we had to have an inquiry commission to know how judges are nominated. That’s not what we do at the CAQ, we talk.”

Cleaning up Quebec’s decades-old corruption mess, big business that might be robbing taxpayers of over $1 billion annually, would not be easy work for the former chief. While he has been described in a way befitting American legend Eliot Ness, Duchesneau wouldn’t walk onto the province's construction sites with a Prohibition-era grin.

His first act to clean Quebec would be more pedestrian, a whistle-blower act to protect those who know what is going on within the sphere of government contracts.

“There needs to be a will from top-down to change things. The problem isn’t tactical or mechanic, it is systemic,” said Duchesneau. “We did not touch the systemic aspect of the problem.

“People who are not elected are able to pull the strings in Quebec right now and that is what we want to change.”