Referendum day, Oct. 30, 1995. The tension was palpable as Quebecers prepared to cast their ballots.

The No camp was gripped with fear that the country's breakup was imminent, while the Yes side was filled with the hope that their dream was finally about to come true.

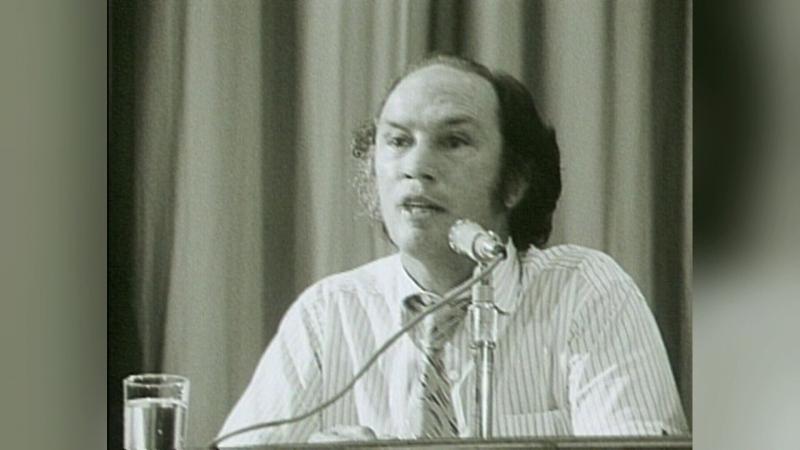

“I'm very happy that at last we've come to the moment of decision. I sincerely hope that everyone who can vote, votes today,” said then-premier Jacques Parizeau at the time.

Robert Valdmanis was on the front lines in Pointe Claire, on a mission to get the No vote out.

“We were certainly nervous but we believed that if we executed it well we would save the country,” he said.

No campaign strategist John Parisella remembers feeling confident, even though the Unity Rally had been held days before the vote. Thousands of Canadians from across the country flocked to Place du Canada downtown for a rally meant as a show of love for Quebecers. Parisella saw the move as a misstep.

“It’s a lot but it’s too late, and it might get a backlash,” he recalls thinking.

On voting day, the turnout was unprecedented: almost 94 per cent of eligible voters made their voices heard. PQ MNA Jean-Francois Lisee was an advisor and speechwriter to Parizeau. The two were side by side at the Palais des Congres watching the results.

Lisee says the Yes camp started the night believing it would win.

“It’s the leader who sets the tone. If he's talkative we're talkative, if he's silent we'll be silent. He decided to be silent. It was a very silent room,” he said.

The Yes vote came out of the gate stronger than expected in parts of the province, but then came surprising results: fewer yes votes in Quebec City and the Beauce. As the votes from Montreal began to trickle in, it became apparent that the tide had turned.

Those at the No headquarters were elated, waving Canadian flags and professing their love for Jean Charest, who at the time was a federal politician involved in the No campaign. At the Yes camp, reality began to set in – stunned faces, tears and hugs as a deep sense of loss hung over the room.

Lisee wrote a concession speech for Parizeau, which Lisee says he read, then put it in his pocket. He never it took out.

“When you look at the speech now, he picked up some of my lines, but not all of them,” Lisee recalled with a laugh. “And he added a couple, and so the night transformed.”

Parizeau blamed the loss on money and the ethnic vote, a statement that would haunt him for the rest of his life.

“My feeling is that he took away the pride that we had had in the campaign,” Lisee said.

On the street, weeks of tension erupted in chanting and in violence. Store windows were shattered and some blood was drawn. But in the end, fewer than 40 people were arrested, only on minor charges.

After the referendum, allegations of spoiled ballots and overspending flew, but went nowhere.

For many on either side, the campaign left a bitter taste time has not erased.

“It’s still very emotional for me. I liken it to having to gamble with someone who doesn't have to ante up. We've done it twice now with great cost, and ever greater potential cost,” said Valdmanis.

Lucien Bouchard, who was the Bloc Quebecois leader at the time, promised Yes supporters that the next time, they’d make it. Twenty years later, the dream appears to be on the backburner, but both sides agree – it’s far from dead.