MONTREAL -- Quebecers will know for certain by Dec. 17 whether they will be permitted to gather for the Christmas holidays, officials said Friday, but even health experts who support the plan say it comes with risk.

Premier Francois Legault said Thursday he would lift restrictions on gatherings for four days -- between Dec. 24 and Dec. 27 -- giving Quebecers time to see friends and family. He asked Quebecers to isolate one week before Christmas and one week after to reduce contagion.

But during a technical briefing a day later, public health officials warned Legault's plan could change if the situation in the province -- which has remained relatively stable for several weeks -- begins to worsen.

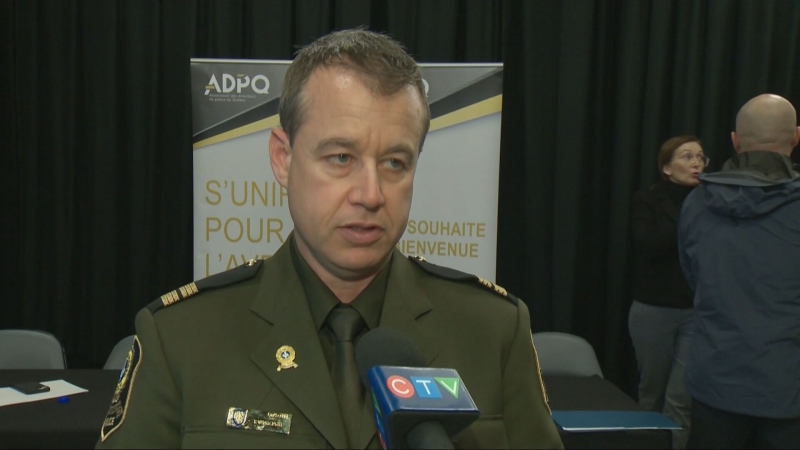

Officials admitted during the briefing, in which public health director Dr. Horacio Arruda participated, that allowing Quebecers to gather during the holidays carries a risk. But, they said, Quebecers would most likely see each other during that period regardless of the rules.

By providing a framework for holiday gatherings, officials said they believed Quebecers would be more inclined to follow the recommendations.

Dr. Earl Rubin, a pediatric infectious disease specialist and medical microbiologist at the Montreal Children's Hospital, said the government's strategy makes sense.

If Legault didn't allow gatherings for Christmas, he said, "people were still going to do it." Rubin said he didn't think it was a "hopeful expectation" that people wouldn't see each other for the holidays.

The premier is "trying to strike a balance between psychological needs of people, the realistic expectations of what people will do, with trying to mitigate the risks of transmission," Rubin said. "I think it was a decent plan."

But there are risks, he warned: "You now have to really cross your fingers and hope for the best that people aren't going to break the rules for New Year's."

Dr. Andrew Morris, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto, said if the government wants to control the pandemic, it needs to send a clear message and discourage gatherings and travel within the province.

"If you're trying to get control of a pandemic, you try and get control of a pandemic," he said in an interview Friday.

"I guess the premier thinks that those gatherings over Christmas are so important that the anticipated increase in cases because of this is worth it."

Morris said he thinks allowing gatherings will send the message that meeting other people indoors isn't dangerous.

"To me, it sends confusing messaging to people," he said. "I'm not sure it's going to make people less likely to gather before that date or after."

On Thursday, Arruda said that while gatherings of up to 10 people will be allowed between Dec. 24 and Dec. 27, they are not encouraged.

For Morris, that's another example of poor communication. "To permit one thing and ask people to do something entirely different makes no sense," he said.

Morris said he didn't know what will happen, but said, "the likelihood that we will see a spike in cases is fairly high."

Dr. Leighanne Parkes, an infectious disease specialist and microbiologist at Montreal's Jewish General Hospital, said it's difficult for governments to "balance societal well-being and morale with maintaining the health of that society."

She said it will now be up to individual Quebecers to ensure that people stay safe during the four day period. "What happens after those four days really depends on the population," she said.

If people isolate before and take precautions when they meet, then COVID-19 won't be "a gift you give the ones you love the most," she said. But, she added, Quebec is still in a "limbo" of partial lockdown with slightly more than 1,000 new cases a day. She said she worries people won't be careful enough.

"It has the possibility of leading to a surge in cases but really the responsibility lies with us," she said. "We have to work together to protect each other."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Nov. 20, 2020.