MONTREAL—Laval’s “mayor-for-life” was once considered an untouchable force in Quebec politics. On Thursday afternoon, Gilles Vaillancourt sat in front of a judge in handcuffs, facing one of the most serious charges in Canadian law.

Vaillancourt had run Laval virtually unopposed since 1989, stepping down last November after a series of raids on his homes, office and bank accounts. The former mayor is now facing 12 counts, including two charges of gangsterism.

Pleading not guilty and released on $150,000 bail, Vaillancourt is the most high-profile casualty yet in the Charbonneau Commission era of Quebec politics.

The lengthy list of other arrestees includes politicians, political aides and people with ties to the construction industry.

It includes, among others, former construction magnate Tony Accurso, Marc Lefrancois of Poly Excavation, former city manager Claude Asselin, and Jean Bertrand, Vaillancourt's former right-hand man.

Those arrested Thursday were arraigned on charges including fraud, breach of trust, corruption in municipal affairs, money laundering.

Robert Lafreniere, the commissioner of UPAC, the permanent provincial anti-corruption squad, said the investigation into criminal activity began three years ago and uncovered a group that conspired to control construction in Laval for their own personal profit.

"We have met with 150 witnesses, we have obtained 164 judicial authorizations and we realized 70 search warrants. We captured approximately 30,000 wiretap conversations, we have recovered $483,000. 120 police officers are involved in today's police operation," said Lafreniere during a morning press conference.

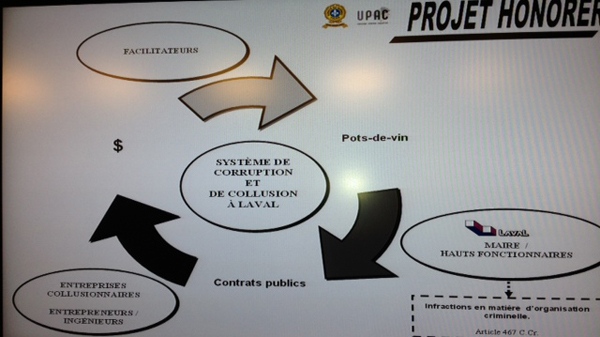

Behind the commissioner was a chart of the criminal organization believed to be in place in Laval, one Vaillancourt is now alleged to have overseen. Lafreniere took pains to point out the three distinct groups in the wide-ranging corruption scheme: entrepreneurs and engineers, lawyers and notaries, and politicians.

This is the first time that gangsterism has been used against a politician in Quebec’s corruption battle, a charge that could be a life sentence for the 72-year-old.

"I will devote all the time that I have to prove my innocence and I think I have very strong points to make," Vaillancourt said Thursday while leaving a Laval courthouse. "I will prove my innocence, I have become a private person and I would like you to respect my private life.”

Not surprised

Emilio Migliozzi of the Mouvement Lavallois told CTV Montreal he was not surprised when he heard of Vaillancourt's arrest.

"It's really a sad day for democracy but a happy one for justice. Justice now will prevail and we hope that the clean up across the city, across the administration of this city will be done next," said Migliozzi.

Robert Bordeleau, leader of the Parti au Service du Citoyen agreed.

"We're on the ground every day or every weekend talking with the citizens and the first question they were asking me is: What's happening with this file. Now everybody knows."

Laval city hall has not had any elected opposition members since 2001, with Vaillancourt and his Parti PRO des Lavallois holding all seats.

Members voted to dissolve the party in Nov. 2012 and all 20 councillors on Laval council now sit as independents.

Resigned following raids

Vaillancourt resigned under a cloud of suspicion on November 9, 2012, following two years of whisperings that he was corrupt.

One month before his resignation police raided his office and his home—returning the next day to raid a condo the mayor also owned.

The then-mayor's name had been mentioned repeatedly by witnesses at the Charbonneau inquiry into corruption in the construction industry.

Former contractor Lino Zambito told the inquiry that Vaillancourt had a hand in every construction project in the fast-growing suburb north of Montreal, personally skimming 2.5 per cent of every publicly financed project.

There are reports that police turned up $40 million in overseas accounts that were traced to Vaillancourt.

In 2010 the mayor faced allegations that he gave the Parti Quebecois envelopes stuffed with cash during the 1994 election and that he gave public contracts to friends and family members.

When those allegations first surfaced Vaillancourt was forced to step down from Hydro-Quebec's board of directors and the Quebec Union of Municipalities.

He has always denied the accusations that he was corrupt, adamantly threatening to sue people who described him as such. That stance faltered as the mayor neared his resignation.

The reaction in Quebec City

In Quebec City, the province’s three main political parties were quick to react to the arrests, each putting its own spin on the news.

Stephane Bergeron, the Parti Quebecois’ public safety minister, told reporters in the National Assembly that his party’s anti-corruption legislation had made suspects nervous—he stopped short of claiming credit for the nine-month-old government.

“I don’t see that as a victory for our government, I see it as a victory for our democracy,” said Bergeron.

The Liberals fired back that they were responsible for establishing UPAC, an attitude Bergeron didn’t appreciate.

“Maybe we should pat ourselves on the back because we helped set up UPAC with them,” said Bergeron.

The Coalition Avenir Quebec’s Jacques Duchesneau, once Quebec’s anti-corruption czar, said not so fast to both parties, pointing out that the Liberals and PQ stalled for 948 days before establishing the specialized unit.

“Where were they?” asked Duchesneau.

Quebec’s mayors were gathered in Montreal for the province’s annual federation of the municipalities meeting on Thursday. Incumbent Laval Mayor Alexandre Duplessis, who once described Vaillancourt as his political mentor, called the arrests a “dark day” for the suburb.

Saguenay Mayor Jean Tremblay voiced his disbelief that corruption might have been going on at a high level for so long without it being detected by authorities.

"When you're a mayor like me, making $135,000 a year plus an expense account, if you want to make more than that, do something else in life," said Tremblay, known for his colourful and sometimes controversial remarks.

"If you feel obliged to rob your citizens on top of that, to do your work, it's serious."

During Vaillancourt's 23 years as mayor Laval grew from a suburb dominated by farmland to the third-largest city in the province. Vaillancourt was known as an effective, powerful mayor who got things done for his citizen, including bringing the metro to Laval.

—with files from The Canadian Press.