The revelry at the Montreal St. Patrick’s parade may turn to protest chants as organizers of the annual anti-police brutality demonstration have decided to merge their march with the parade.

The Collective Opposed to Police Brutality posted on its website the dates of two demonstrations, one of them to coincide with the St. Patrick’s parade.

The protest announcement on the site is calling for people to dress in green and blend into the crowd, and titled their demonstration in French, “La St-Patrack.”

Kevin Murphy, a spokesperson for the St. Patrick's parade, said he hopes the protest will not get out of control.

"We are a little disappointed to hear that there is going to be a demonstration alongside the parade or within the parade itself," said Murphy. "We're hopeful that they decide instead to celebrate with the rest of Montreal and enjoy the good spirit that's there that day."

Originally, the anti-police brutality protest was to be only on March 15. However, the organizers decided to add a second protest date to join the St. Patrick’s parade on March 22. Demonstrators will be meeting at 1:30 p.m. at Normand Bethune Square.

Francois Du Canal, a member of the collective, explained that protesters wanted to add a second date so they could blend into an existing event and police would not be able to stop their demonstration.

“In the last two years, the protests didn’t even start because police have blocked us,” said Du Canal. “So we’re obliged to do this so we can exercise our right to protest and take to the streets.”

Du Canal acknowledges that families with young children will be at the St. Patrick’s parade, but he said it will not be the fault of protesters if there is any violence.

“One thing for sure, no one will hurt families,” said Du Canal. “We’re not against St. Patrick’s Day. If there’s any violence, it will be coming from police.”

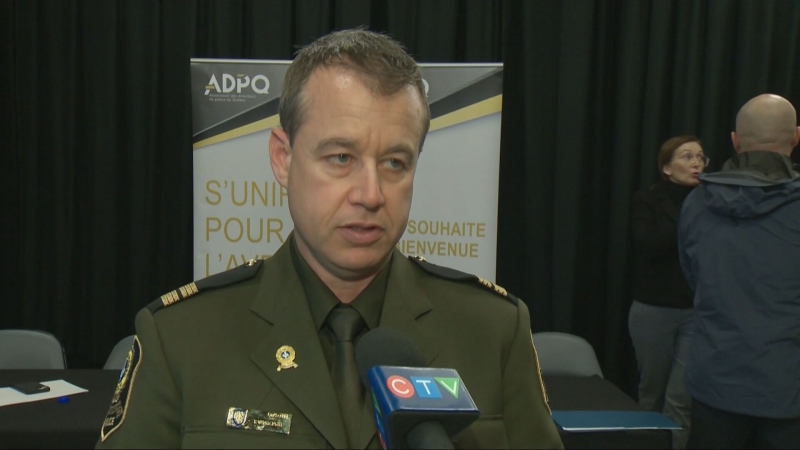

The parade’s organizers haven’t approached police about extra security for the parade, but Montreal police Cmdr. Ian Lafreniere pointed out that with warmer weather comes protests, and with protests come reminders from the police regarding what the law allows.

“There’s been some talk lately about [bylaw] P-6, but it’s still there and it [obligates] a person in charge of a protest to share the route, share the itinerary, and if not the people who take care of that protest that is declared illegal will be booked and will receive a ticket,” he said.

The anti-police brutality protests have a history of turning violent, ending with arrests and fines. Organizers for the collective do not provide police with their itineraries, which goes against municipal bylaw P-6.

In 2014, police declared the protest illegal, and gave out 288 fines and arrested five people.

The largest police roundup in the event's history took place in 2002, when 370 were detained.