Thousands are homeless and the death toll could rise as Biblical-scale inundations continue to ravage Houston, Texas.

The metropolis, overtaken by flood water, is emptying out—an estimated 30,000 people are in shelters, airports and major autoroutes are unusable, and experts estimate that damage caused by hurricane Harvey could have extended over 30-50 separate counties in the region.

However, science still has a way to go in assessing whether or not climate change is directly linked to the generation of such extreme weather events.

Meteorologists throughout North America continue to weigh in ominously on the “unprecedented” damage left by the hurricane as it continues its destructive path through coastal regions.

Some experts believe that the destruction could be attributable to the fact that Harvey – a “strong summer hurricane”—is hitting an unfortunate spot, where it’s expected to linger and continue to dump huge amounts of rain.

But will there be more Harveys on the horizon in light of climate change issues?

Although climate experts are hesitant to say that the hurricane is definitively linked to global warming—especially considering the “complicated” trajectory of hurricanes — there is a potential link between human activity and the storm’s breakneck momentum.

What does the science say?

According to experts in the field, climate change does generally cause average storms to intensify-- hurricanes will strengthen more rapidly in warming climates.

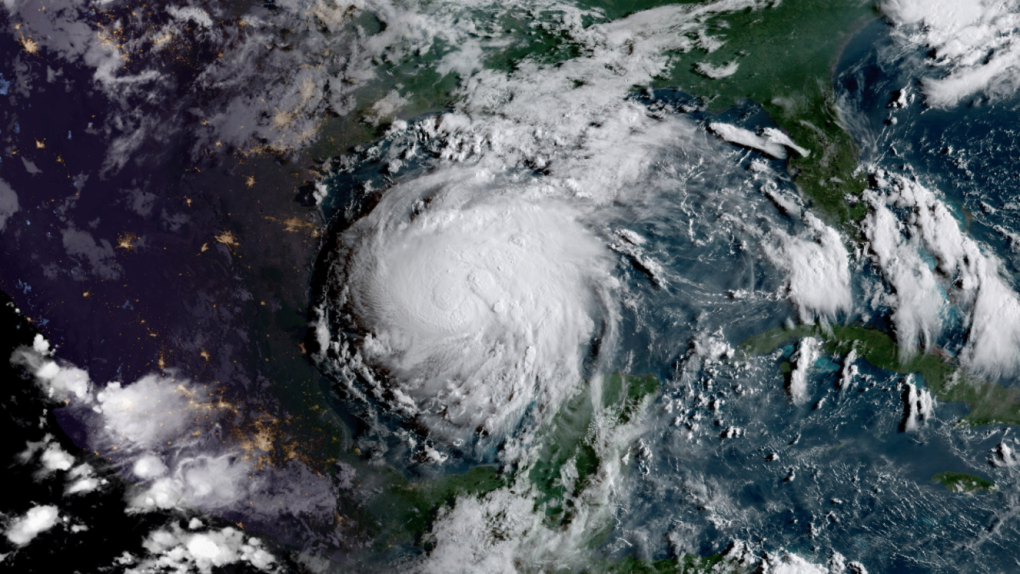

This is essentially what climate change experts consider the most striking aspect of hurricane Harvey: how quickly the storm intensified.

On Friday, Harvey was considered a tropical storm, with winds at 45 mph. By Friday, it had intensified to a category 2 storm, with roaring winds of 110 mph.

In the past 30 years of records, no storms west of Florida have intensified in the 12 hours before landfall—however, Harvey escalated to a category 4 storm before hitting the Texas coast.

“We normally see them coming, yet the character, the personality of them—sometimes you just don’t know it until the end,” Dave Phillips, a senior climatologist with Environment Canada, told CTV National News.

“It almost exploded—like a weather bomb. It went from a no-name event to a category four—with winds over 200 mph — in 56 hours,” Phillips explained.

A study published by the American Meterological Society earlier this year found that “24 hour pre-landfall intensifications of 100 [knots], which are essentially nonexistent in the late twentieth-century climate may occur as frequently as once per century by the end of this century,” and concluded that global warming “substantially” increases the rapid intensification of storms before they hit the ground.

Although analysts predict that there may be fewer hurricanes in the future, the intensity of tropical storms is increasing with time and as a result of some human activities.

Two factors can potentially worsen in time – storm surge and rainfall – and these are what experts consider to the deadliest, most destructive parts of the storm.

These rapid-building storms tend to yield more fatalities and destruction since people have less time to prepare for them.

Another study conducted in 2010 said that storm-related damage could increase by an average of 30 per cent by the end of the century.

With an estimated $515.4 billion of damage caused by hurricanes over the last three decades—future damage could be devastating and increasingly difficult to repair.

But in order to argue that climate change may play a role in fueling hurricanes, one has to understand the factors that contribute to their power.

Hurricanes typically form over large bodies of warm water, deriving energy from the evaporation of water from the ocean surface.

As the world warms, evaporation speeds up, generating more water vapor for storms to sweep up and dump on storm areas.

Statistics show that the sea level along the Texas coast was the highest it’s been in 100 years due to melting glaciers and the swelling of the ocean surface.

NASA estimates a sea level increase of 3.4mm a year – a figure that seems negligible, but that has already visibly increased storm impact.

For example, sea level during hurricane Sandy in 2012 was nearly a foot higher than usual – if the same hurricane had touched down in, say, 1912, it would not have flooded lower Manhattan.

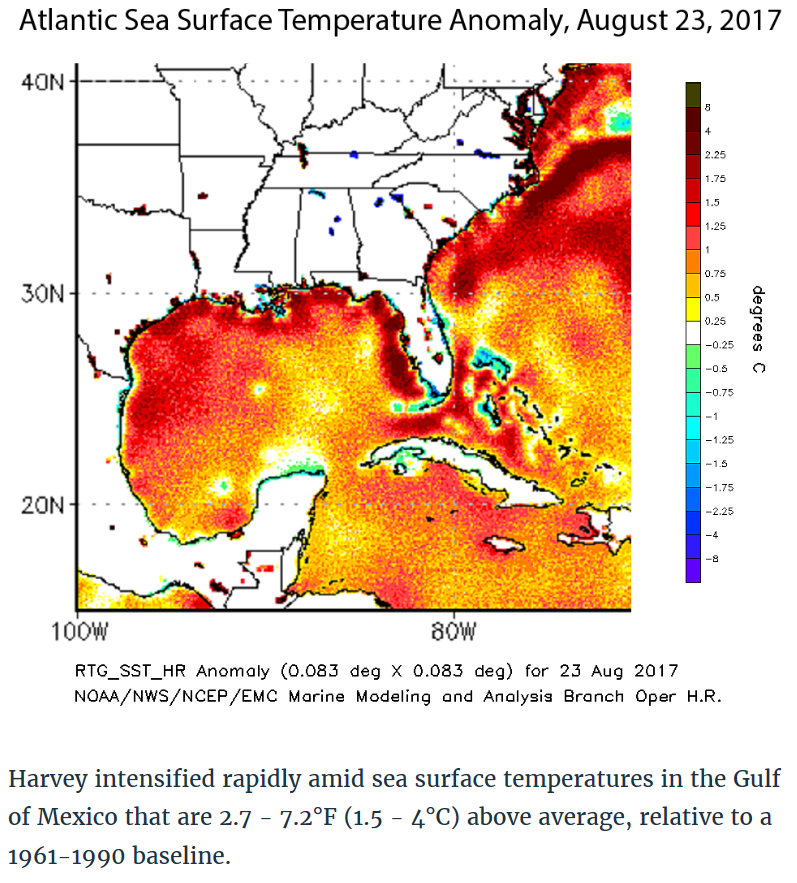

The temperature of the water was also remarkably higher than the norm. An infrared map on the Climate Signals website shows that the water temperature in the Gulf of Mexico was between 2 and 7 degrees Fahrenheit higher than the 30-year baseline average.

At the time that Harvey began to gain momentum, the Gulf was one of the hottest spots of ocean surface in the world – acting as “fuel” for a tropical storm, enabling the hurricane to churn up water from almost 200 meters below the ocean surface.

Storms weaken once cold water is churned up from below, so the warmer the water—the fiercer the storm will be.

Although the consensus seems to be that a storm of this magnitude could have occurred when there was no climate change, the devastation was exacerbated by aspects of climate change.

Hurricane Harvey: a man-made phenomenon?

Certain experts and columnists have made some tentative connections between Houston’s industries and day-to-day functions as a facilitator for severe weather.

A 2016 study conducted by the European Geosciences Union revealed that anthropogenic climate change—climate change as a result of human activity – increased the probability of extreme rainfall on the Gulf Coast by 1.4 times.

Now, considering that Houston is the self-proclaimed capital of fuel production in the US—specializing in gas and oil—there may be a feasible link between the extreme weather and the constant emission of greenhouse gases.

There are 5000 energy-related firms in the area, 17 of which are on the Fortune 500 list and comprise some of the largest companies in the US.

According to meteorologist and former Wall Street Journal columnist Eric Holthaus, Houston has been ground zero for extreme weather in recent years.

Heavy downpours in Houston have increased by 156 per cent since the 1950’s, and the city has seen four 100-year flooding events since spring of 2015.

Greenhouse gas emissions, ultimately linked to an increase in temperature, also enables the atmosphere to hold more moisture—roughly 7 per cent more with each degree added to the baseline temperature.

Ken Trenberth, a senior scientist at the US National Center for Atmospheric Research, told The Atlantic that human contribution may account for approximately 30 per cent of the total rainfall coming out of the storm.

So far, however, scientists have not been able to successfully prove that extreme weather events wouldn’t occur at all if not for global warming – but the examples of how global warming has amplified the catastrophe are only increasing.

Understanding the precise links to global warming—even broadly—helps the public understand what risks are posed by climate change, experts say.

Maps like the one below, generated by the Esri Disaster Response Program, tracks current and/or recent locations of tropical storms.