People who suffer from seasonal allergies – that’s a good 15 per cent of the population – are in for an extended bout of sniffles this year.

Due to the warm spring, plants began producing pollen early – and they won't let up until the first frost.

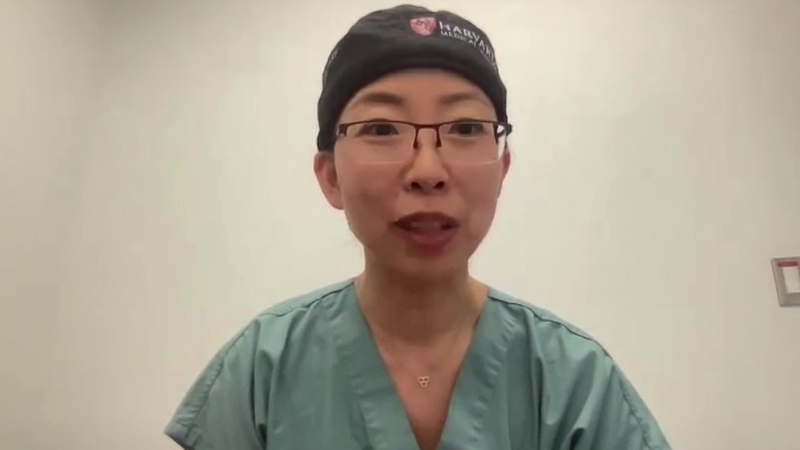

Ragweed plants take time to mature before they produce pollen, usually at the end of August, said Dr. Christine McCusker, Montreal Children’s Hospital.

“It started creeping up to the middle of August and now this year, especially with that really warm spring, it really started to affect patients beginning of August,” said McCusker.

Allergy symptoms can create a domino effect, she said.

“If your nose is congested, you don't sleep as well, you don't sleep as well, you're tired at work the next day, your productivity is down.

For decades, Montreal municipalities tried to control the spread of the plant, by requiring property owners to remove it, but there weren't enough inspectors to ensure it was managed.

In 1992, a group of ragweed sufferers filed a $360-million class action lawsuit against Montreal municipalities to try and get them to enforce their own bylaw.

The bylaw was repealed in 1996 and the claim was rejected by the court.

The encouraging news, however, is that scientists are making progress on the costly issue - The Lung Association says medical complications due to hayfever and other seasonal allergies cost the Quebec health system $157 million each year.

“We started looking to see if in an animal that was allergic to ragweed - could we treat them? And what we found was by giving this little bit of this protein and you just spray it up the nose as a little nasal spray, once, one treatment course completely blocked the immune response leading to allergies,” said McCusker.

It's also possible the same molecule could someday be used as a vaccine, though it may take five to ten years.